Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

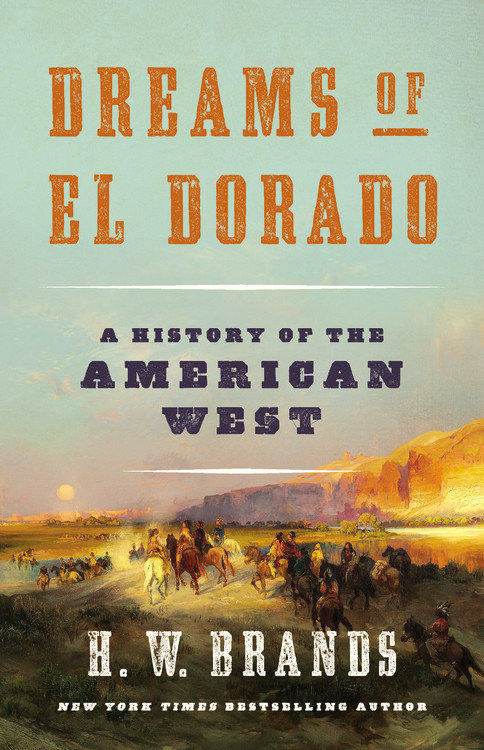

Dreams of El Dorado

A History of the American West

Contributors

By H. W. Brands

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 22, 2019

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541672529

Price

$32.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- Digital download $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 22, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Epic in its scale, fearless in its scope, this is a bravura performance from one of our master historians.” —Hampton Sides, bestselling author of Blood and Thunder

In Dreams of El Dorado, H. W. Brands tells the thrilling panoramic story of the settling of the American West, from Lewis and Clark’s expedition in the early nineteenth century to the closing of the frontier by the early twentieth. He introduces us to explorers, mountain men, cowboys, missionaries, and soldiers, taking us from John Jacob Astor’s fur-trading campaign in Oregon to the Texas Revolution, from the California gold rush to the Oklahoma land rush. Throughout, Brands explores the contradictions of the West and explodes its longstanding myths. The West has been celebrated as the proving ground of American individualism; in reality, the West depended on collective action and federal largesse more than any other region. The West brought out the finest and basest in those who ventured there, evoking both selfless heroism and unspeakable violence. Visions of great wealth drew generations of Americans westward, but El Dorado was never more elusive than in the West.

Balanced, authoritative, and masterfully told, Dreams of El Dorado sets a new standard for histories of the American West.

-

"Lively...[Brands] knows how to write in a popular style that draws us in and holds our interest...[He] also pauses to make some thought-provoking insights, which round out the narrative and present his subject in a fresh light...An engaging, eminently readable introduction."Wall Street Journal

-

"An exciting new history of the American West and how it was settled, from the California gold rush to the Oklahoma land rush and more."New York Post

-

"[Brands] has a deft narrative touch and a talent for highlighting the human drama undergirding historical events...History as adventure story."Los Angeles Review of Books

-

"[A] fine new history."Houston Chronicle

-

"Brands surveys the past three centuries of the West, chronicling all-too-human tales of hope, greed, triumph, tragedy, and irony. His history is propelled by the stories of amazing characters, some famous, others obscure...A marvelous short history of the West, rewarding both expert and neophyte readers."Booklist (starredreview)

-

"Brands is a master storyteller...[Dreams of El Dorado] will enthrall aficionados of 19th-century American history."Library Journal

-

"A lively, well-written survey full of novel observations on a region shrouded in legend."Kirkus

-

"Brands argues convincingly that the reality of the American West was very different than the way it was mythologized...Lucid prose and short, tightly focused chapters...This broad but clearly structured study, with its many well-chosen illustrations, is likely to have wide appeal."Publishers Weekly

-

"The expansion of the United States across what would become the American West is the sort of sprawling, tumultuous epic that is best told by a calm and concentrated mind. Fortunately the author of this book is H.W. Brands, who has the vision and supreme narrative skill to braid the chaotic tendrils that make up the past into a story that is almost as exciting for its coherence as it is for the heroic and heartbreaking events it so vividly renders. Dreams of El Dorado is the latest reason to think of Brands as America's go-to historian."Stephen Harrigan, author of Big Wonderful Thing and The Gates of the Alamo

-

"A subject this monumental demands prose to match it, and I am pleased that to report that, in this sprawling epic, H. W. Brands is at his sparkling best. He is of the American West and grew up in its myths, which may explain why he writes about it with such passion and clarity."S. C. Gwynne, New York Times bestselling author of Empire of the Summer Moon and Rebel Yell

-

"The 'winning' of the American West is that biggest and most daunting of subjects, so big that most historians have found it necessary to bite off small corners of this grand and sordid tale of empire-building. But here H.W. Brands endeavors to tell it all, from Texas to California, from beaver pelts to buffalo robes, from the hoofbeats of horses to the steam blasts of the first transcontinental trains. Epic in its scale, fearless in its scope, this is a bravura performance from one of our master historians."Hampton Sides, bestselling author of Blood and Thunder