By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

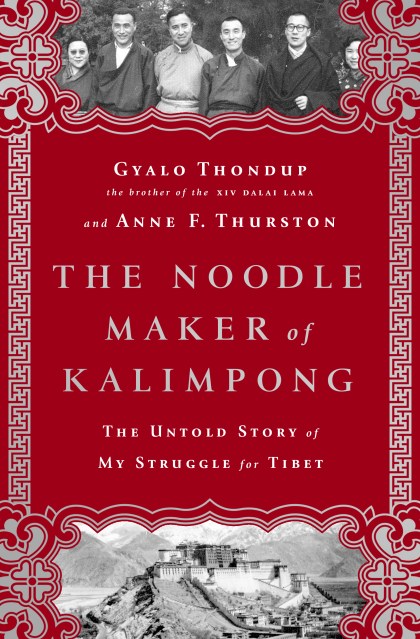

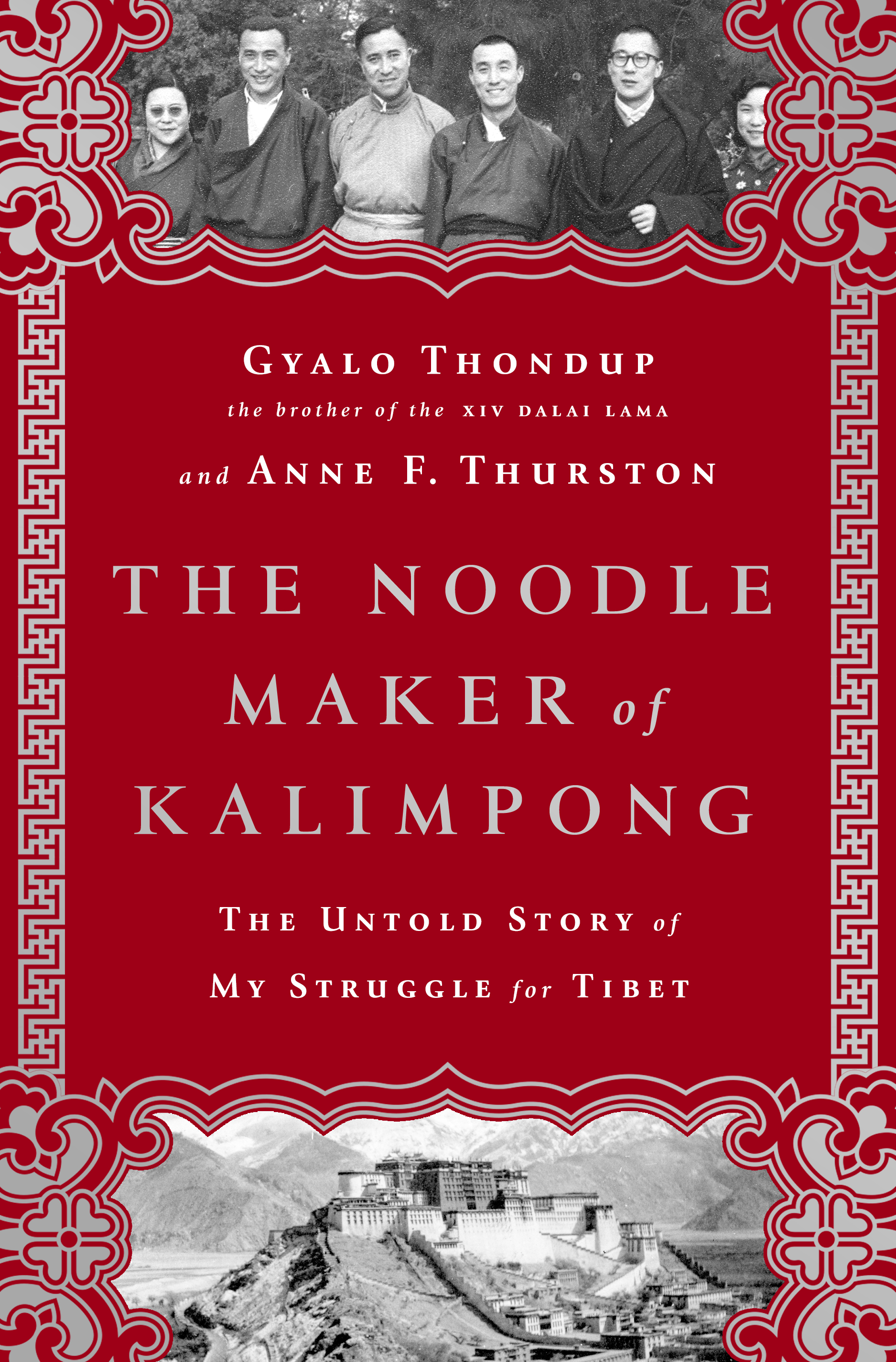

The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong

The Untold Story of My Struggle for Tibet

Contributors

By Anne F Thurston

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 14, 2015

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392907

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.99 $34.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 14, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong tells the extraordinary story of the Dalai Lama’s family, the exile of the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism from Tibet, and the enduring political crisis that has seen remote and bleakly beautiful Tibet all but disappear as an independent nation-state.

For the last sixty years, Gyalo Thondup has been at the at the heart of the epic struggle to protect and advance Tibet in the face of unreliable allies, overwhelming odds, and devious rivals, playing an utterly determined and unique role in a Cold War high-altitude superpower rivalry. Here, for the first time, he reveals how he found himself whisked between Chiang Kai-shek, Zhou Enlai, Jawaharlal Nehru, and the CIA, as he tried to secure, on behalf of his brother, the future of Tibet.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use