Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

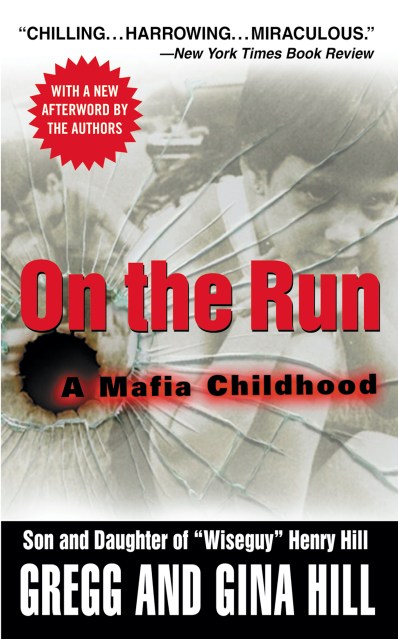

On the Run

A Mafia Childhood

Contributors

By Gregg Hill

By Gina Hill

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Henry Hill’s business partner, Jimmy Burke, has whacked every person who could possibly implicate him in the infamous Lufthansa robbery at JFK airport. On his way to prison, lifelong gangster Henry is given two options: sleep with the fishes, or enter the FBI’s Witness Protection Program.

Unfortunately for his children Gregg and Gina, they’re dragged along for the ride. Like nomads, they’re forced to wander from state to state, constantly inventing new names and finding new friends, only to abandon them at a moment’s notice. They live under constant fear of being found and killed.

But Henry, the rock Gregg and Gina so desperately need, is a heavy cocaine user and knows only the criminal life. He is soon up to his old tricks and consistently putting their identities in jeopardy. And so it continues until the kids, now almost grown, can no longer ignore that the Mob might be less of a threat to them than remaining under the roof of their increasingly unbalanced father.

Genre:

-

"Henry Hill lived life dangerously close to the edge, and nearly pulled his family into the abyss. That his children survived to tell this fascinating tale is a testament to their resolve."Nicholas Pileggi, Author of Wiseguy

-

"Gripping... an unforgettable portrait of life inside the Mob... This book is proof of the bravery of children who refused to accept their father's legacy."Sam Giancana, Author of Double Cross

-

"Remarkable... absolutely the best book about growing up with a wiseguy father -- and I've read them all... plenty of riveting, juicy detail... Only the children of Henry Hill could've written this intimate exposé, and they've done it with gut-wrenching honesty and incredible courage."Pete Earley, Author of Witness: Inside the Federal Witness Protection Program

-

"Mob children are the hidden victims of organized crime... their story has never been adequately told until now... A must-read for those who want the complete picture of life in the Mafia."Anthony Bruno, Author of Bad Guys

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2007

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446534710

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use