By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

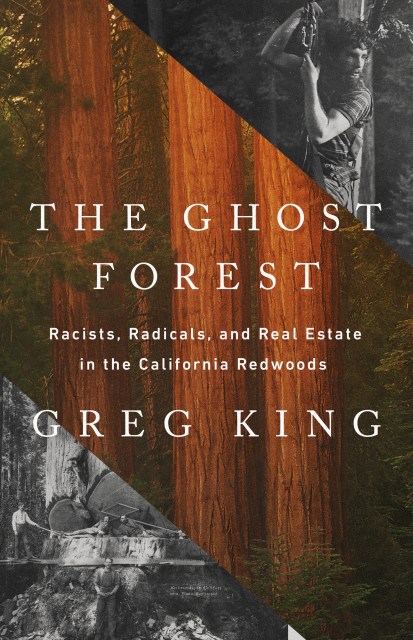

The Ghost Forest

Racists, Radicals, and Real Estate in the California Redwoods

Contributors

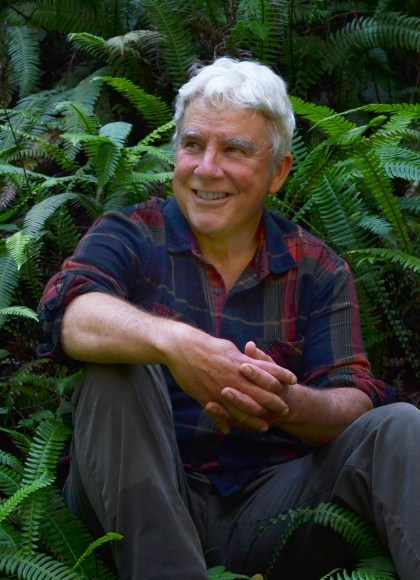

By Greg King

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 6, 2023

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541768673

Price

$35.00Price

$45.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 6, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Every year millions of tourists from around the world visit California’s famous redwoods. Yet few who strain their necks to glimpse the tops of the world’s tallest trees understand how unlikely it is that these last isolated groves of giant trees still stand at all. In this gripping historical memoir, journalist and famed redwood activist Greg King examines how investors and a growing U.S. economy drove the timber industry to cut down all but 4 percent of the original two-million-acre redwood ecosystem. King first examined redwood logging in the 1980s—as an award-winning reporter. What he found in the woods convinced him to leap the line of neutrality and become an activist dedicated to saving the very last ancient redwood groves remaining in private hands.

The land grab began in 1849, when a “green gold rush” of migrants came to exploit the legendary redwoods that grew along the Russian River. Several generations later, in 1987, Greg King discovered and named Headwaters Forest—at 3,000 acres the largest ancient redwood habitat remaining outside of parks—and he led the movement to save this grove. After a decade of one of the longest, most dramatic, and violent environmental campaigns in US history, in 1999 the state and federal governments protected Headwaters Forest.

The Ghost Forest explores a central question, an overhanging mystery: What was it like, this botanical Elysium that grew only along the Northern California coast, a forest so spectacular—but also uniquely valuable as a cornerstone of American economic growth—that in the end it would inspire life-and-death struggles? Few but loggers and surveyors ever saw such magnificent trees, ancient sentinels that, like ghosts, have informed King’s understanding of the world. On a lifelong journey, King finds himself through the generations, and through the trees.

A Next Big Idea Club Must-Read Title

-

“Groundbreaking… an epic tale of corruption and deception, perpetrated on a mass scale for nearly a century.”The Atlantic

-

“How many people who travel to see California’s coniferous giants know why they’re still standing? King, a journalist and dedicated redwood activist… considers the ecosystem itself and how it affects its surroundings, using his lifelong love of these mighty ‘ghosts’ to bring them to life.”Los Angeles Times

-

“Greg King is an authoritative guide… The Ghost Forest triumphs as a comprehensive accounting of events and entities that ushered in this irreplaceable loss… Although set in the past, the book is urgently of-the-moment… the systems of power and wealth that targeted the redwoods and their protectors continue to inflict violence on Earth’s defenders worldwide.”Science magazine

-

“Haunting … [a] wholly engrossing, urgent account of redwood preservation.”Kirkus, starred review

-

“King’s dogged research turns up the closed-door deals and nefarious legal schemes that led to the destruction of 96% of redwood forests, providing a disturbing chronicle of how lumber companies flouted laws and came out on top. The result is a sobering accounting of the forces environmentalists are up against.”Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

“The Ghost Forest is the book I’ve long wished someone would write, and Greg King has done it luminously well. He tells the epic story of the destruction of 96 percent of the primeval redwoods in California—including the criminal and bankrupt horrors of ‘liquidation logging’ done in the 1980s and 90s by corporate raider Charles Hurwitz and the Maxxam Corporation. And he tells the story of activists and protesting tree climbers (including himself) who put their lives on the line to save the Headwaters Forest Reserve, a jewel of the redwood realm.”Richard Preston, author of The Wild Trees and The Hot Zone

-

“The farther I traveled into The Ghost Forest the more convinced I became I was reading an epic. It is encyclopedic in historical knowledge and detail, deeply felt in its love of redwood country, and fierce in its passion for saving the last remnants of old growth forest from rapacious and unconstrained capitalism.”Charles Frazier, author of Cold Mountain and The Trackers

-

“Ghost Forest is a haunting requiem for one of Earth’s magnificent forests. Human survival has rested on our ability to recognize opportunity by exploiting the planet’s abundance. Once armed with fossil fuels and machines, we have felled entire ecosystems to serve our limitless demands. King’s feelings of awe, humility, and love before giant redwoods are needed to slake our drawdown of the rest of nature.”David Suzuki, OBE, international climate activist and author of Tree: A Life Story

-

“King is an American hero. And he has written a heroic book—a book befitting the California redwoods, which are the tallest, the oldest, and arguably the most magnificent creatures on the planet. The Ghost Forest is a stunning work: beautifully written, exquisitely researched, compelling, funny, angry, poetic, cynical, idealistic, and always fascinating. King’s important reinterpretation of the history of the Save‑the‑Redwoods League reads like a detective novel. We are all in King’s debt for having the courage to tell his story, and to tell it so beautifully.”Jonathan Spiro, author of Defending the Master Race

-

“In this combination of memoir and investigative report, King, veteran of the Northern California timber wars, evokes the spirit of the long‑gone fog shrouded giants that fell to axe and saw. He paints a picture both inspiring and disturbing of the heroic forest defenders, the intractable timber beasts, and the nefarious opportunists that played the two sides against each other for their own profit. He takes us on one final journey across the sacred ground where the great booming forests once stood and are now lost forever.”Will Russell, professor of environmental studies, San Jose State University

-

“This book is the story of one man’s fight to save the planet’s tallest trees. As a young man, King risked everything to stop logging companies from hacking down the last big California redwoods. The Ghost Forest brilliantly recounts his odyssey to make sense of the millennial mystery and modern history of the great forest. It’s an unforgettable story, and one more necessary than ever with the future of the earth itself under threat.”Orin Starn, professor of history, Duke University, and author of Ishi’s Brain

-

“The Ghost Forest is a tale both infuriating and inspiring. It covers the destruction of California’s redwood forests, told from a perspective that could not be more up close and personal. From its gripping opening scene of activist vs logger, to its unfolding story of the magnificent trees themselves, the book rushes with the energy of a river in spring. All of us who care about the future of human existence on the planet, and who want to understand the ways in which that future can be compromised, need to read this story.”Bruce Cockburn, International music star, author of Rumours of Glory

-

“Writing about redwoods is hard because of the ancient forest’s unimaginable grandeur, in space and time, and because of the sickening violence and waste of its almost complete destruction in less than two centuries. Greg King has written about it exceptionally well, and with good cause. Having grown up in the “Redwood Empire,” he has spent much of his life exploring the forest, on the ground and in libraries. He knows the tangled politics of forest destruction and protection in great detail from personal participation and observation. He has risked his life more than once to find and help save significant “last stands” like the Headwaters Forest. And he writes about it all with poetic fervor, scientific precision, political wisdom, and a droll, self‑deprecating sense of humor that brings the adventuresome days of Earth First! and tree‑sits to life with a clarity that is in wonderfully refreshing contrast to the muddle of mass media coverage.”David Rains Wallace, author of The Klamath Knot

-

“The Ghost Forest is long overdue. The book is a page‑turner, a calibrated adventure of the highest sort. At last we have a comprehensive accounting of the entire ancient redwood ecosystem that once stood, who cut it down, and who stepped up to save these fabulous trees—a story necessarily written by the most committed of redwood defenders. I have followed Greg King’s work since 1987, just after he left a successful career as a journalist to lead an audacious fight for the last redwoods. Yet it is this journalist’s eye for detail, and for the complex history of redwood logging and protection, that makes The Ghost Forest such an important contributor to the canon of American conservation.”Yvon Chouinard, founder, Patagonia, Inc.

-

“The Ghost Forest captures the adventure and dangers of early redwood exploration and the evolution of a modern preservationist from an insider’s perspective. Here Greg King explores threatened historic redwood groves which had never been seen before, and brings to life untold stories of the fight to preserve these last forests.”Erv Peterson, Professor Emeritus, Environmental Studies, Sonoma State University

-

“Passionate… King’s engaging narrative exposes the maneuvering of lumber companies that plundered redwood forests for decades, with the collusion of powerful individuals in politics, academia, and civil service.”Library Journal

-

“Deeply researched and compellingly written.”Times Literary Supplement

-

“A celebrated activist for the California redwoods holds nothing back in this indictment of the organizations to blame for cutting down almost the entire redwood forest in the name of economic growth.”Saturday Evening Post

-

“Likely to become a classic. ... For anyone concerned with the environment and its defense, this book is an essential read.”North Coast Journal

-

“A classic tale of David meeting Goliath … will likely become a fast favorite for anyone interested in the fate of trees.”Cascadia Daily News

-

“Greg King is the sole person who could have researched and written this definitive history. The story King tells is personal, riveting, and blunt.”Environmental History

-

“A shocking and entirely unexpected story. King, with his generations-long connection to the redwood forests, is the perfect person to tell the tale.”Amy Stewart, The Week

-

"Greg King is an excellent writer. … This is a big book, and an important one."National Parks Traveler magazine