Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Killing Titan

Contributors

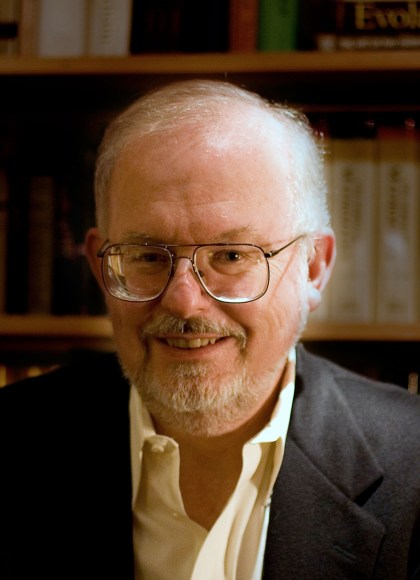

By Greg Bear

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 5, 2016

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316223980

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- ebook $5.99 $7.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 5, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

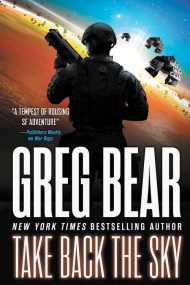

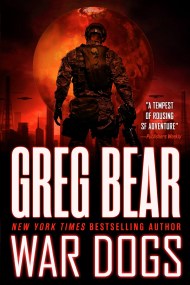

After barely surviving his last tour on Mars, Master Sergeant Michael Venn finds himself back on earth in enforced isolation. Through a dangerous series of operations he returns to Mars to further his investigation into the Drifters — ancient artifacts suddenly reawakened on the red planet.

But another front in the war leads his team to make the difficult journey to Saturn’s moon, Titan. Here, in the cauldron of war, hides new truths about the Drifters, the origin of life in our solar system and the plans of the supposedly benevolent Gurus, who have been “sponsoring” and supporting humanity in their fight against outside invaders.

Killing Titan is the second book in the epic interstellar War Dogs trilogy from master of science fiction, Greg Bear.

Series:

-

"Stuffed with adrenaline-pumping action and mystifying ambiguity, Bear's series launch is a tempest of rousing SF adventure with a dash of Peckinpah."Publishers Weekly on War Dogs

-

"Military sci-fi, action and adventure, and a whole lot of thought-provoking complexity."San Diego Union-Tribune on War Dogs

-

"Packed with adventure and incident...and conveyed with gritty realism."Kirkus on War Dogs

-

"Greg Bear's voice is a resonant, clear chord of quality binding some of the best SF of the 20th Century to the short list of science-savvy, sophisticated, top-notch speculative fiction of the 21st. More than a grace note, Hull Zero Three is a compelling allegro in the growing symphony of Greg Bear's finest work."Dan Simmons

-

"Hull Zero Three is a grand adventure of scientific discovery in the tradition of "Orphans of the Sky" and "Rendezvous with Rama" -- by turns chilling and touching, it poses challenging questions about what it means to be human."Charles Stross

-

"Hull Zero Three is a lean, mean, supercharged sense-of-wonder engine."Alastair Reynolds on Hull Zero Three

-

"Not for those who prefer their space opera simple-minded, this beautifully written tale where nothing is as it seems will please readers with a well-developed sense of wonder."Publisher's Weekly (starred review) on Hull Zero Three

-

"Greg Bear is one contemporary master of the old ways, and in Hull Zero Three he gives the generation starship theme - crystallized beautifully by Robert Heinlein in 1941's "Universe" - a vigorous makeover...."bn.com

-

"The heart of the mystery is worthy of Bear in its bravura extrapolations into far-future science and moral ambiguity...a testament of faith both in human beings and in something beyond them, divine or indistinguishable from it, and it seems directed as much toward the world of today, with all its sinful affections and deceits, as it is toward the far future."Locus on Hull Zero Three

-

"I loved Hull Zero Three - this book reminds me of why I fell in love with science fiction in the first place. Searing questions of humanity, a good old fashioned riddle of a plot, and excellent conceptualization make Hull Zero Three more than worth the effort."thebooksmugglers.com