Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

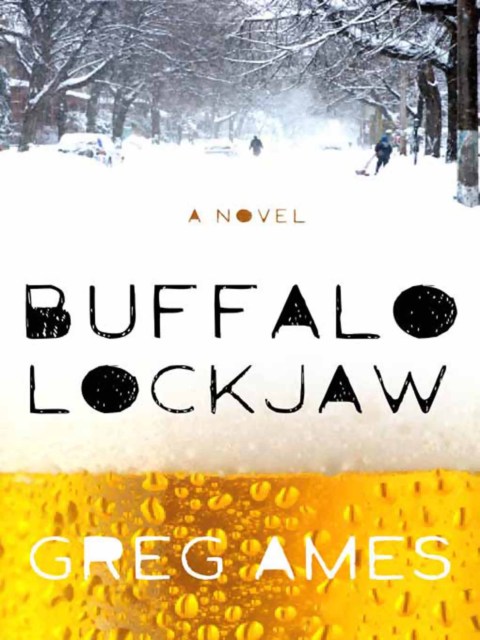

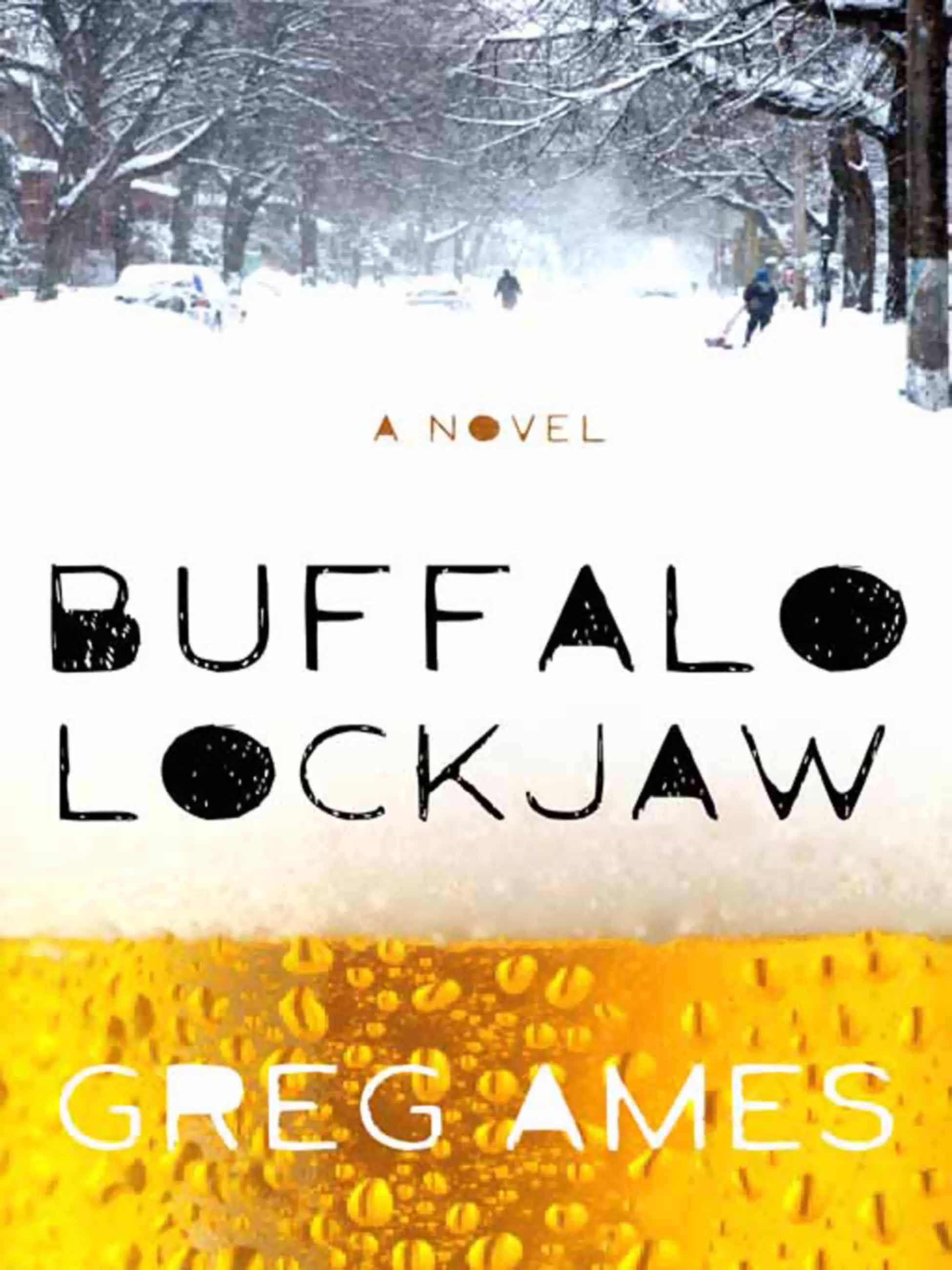

Buffalo Lockjaw

Contributors

By Greg Ames

Formats and Prices

Price

$6.99Price

$8.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $6.99 $8.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 1, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

James Fitzroy isn’t doing so well. Though his old friends in Buffalo believe his life in New York City is a success, in fact he writes ridiculous taglines for a greeting card company. Now he’s coming home on Thanksgiving to visit his aging father and dying mother, and unlike other holidays, he’s not sure how this one is going to end. Buffalo Lockjaw introduces a fresh new voice in American fiction.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 1, 2009

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401395315

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use