By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

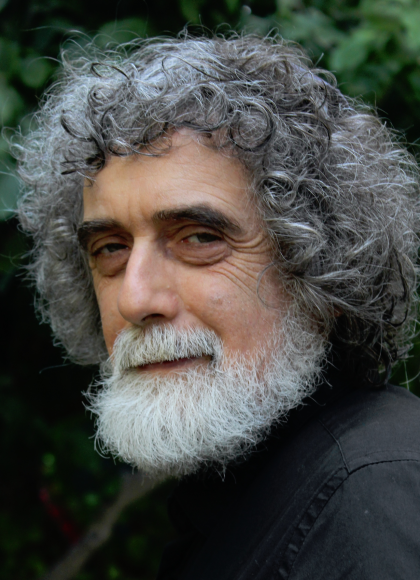

War of Shadows

Codebreakers, Spies, and the Secret Struggle to Drive the Nazis from the Middle East

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 11, 2022

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541702677

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 11, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this World War II military history, Rommel’s army is a day from Cairo, a week from Tel Aviv, and the SS is ready for action. Espionage brought the Nazis this far, but espionage can stop them—if Washington wakes up to the danger.

As World War II raged in North Africa, General Erwin Rommel was guided by an uncanny sense of his enemies’ plans and weaknesses. In the summer of 1942, he led his Axis army swiftly and terrifyingly toward Alexandria, with the goal of overrunning the entire Middle East. Each step was informed by detailed updates on British positions. The Nazis, somehow, had a source for the Allies’ greatest secrets.

Yet the Axis powers were not the only ones with intelligence. Brilliant Allied cryptographers worked relentlessly at Bletchley Park, breaking down the extraordinarily complex Nazi code Enigma. From decoded German messages, they discovered that the enemy had a wealth of inside information. On the brink of disaster, a fevered and high-stakes search for the source began.

War of Shadows is the cinematic story of the race for information in the North African theater of World War II, set against intrigues that spanned the Middle East. Years in the making, this book is a feat of historical research and storytelling, and a rethinking of the popular narrative of the war. It portrays the conflict not as an inevitable clash of heroes and villains but a spiraling series of failures, accidents, and desperate triumphs that decided the fate of the Middle East and quite possibly the outcome of the war.

-

"Vivid...fascinating...sure to be among the year's best histories of World War II."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"Richly detailed...deeply researched account."Publishers Weekly

-

"A solid analysis of how espionage impacted an important theater, this book should appeal to anyone interested in World War II history, particularly intelligence operations."Library Journal

-

“A groundbreaking work.”The Jerusalem Post

-

“War of Shadows is a fascinating look at the politics of the Middle East, a region that would explode after the war, written with a thriller writer’s sense of character and timing.”Shepard Express

-

“A breakthrough book by Gershom Gorenberg featuring uncovered secrets from World War II reveals how easily the war could have gone the other way…In an effort of meticulous historical research, Gorenberg has pieced together the intelligence saga behind the war for North Africa.”Haaretz

-

“A masterpiece of scholarship and synthesis…The highest praise that can be bestowed on his book is that it will remind readers of a cloak-and-dagger tale by John Le Carré with an armature of fascinating historical annotation.”The Washington Post

-

“The deeply researched book brims with anecdotes and rich details… shedding much needed light on a long-overlooked period and part of the war.”Times of Israel

-

“A fast and gripping read."New York Journal of Books

-

“The story grips you so much that it’s hard to put aside: the extraordinary spying in both directions, the vivid characters, the huge stakes, and all of this on a World War II front that American readers know surprisingly little about.”Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopold's Ghost

-

“With the pacing of a spy thriller… War of Shadows takes us to the brink of disaster as the Allies and Axis powers vie for control of the Middle East…. Gorenberg belongs to a unique cadre of journalist historians.”Sarah Wildman, author of Paper Love

-

“A dazzling and groundbreaking portrait of a crucial moment in WWII… Gorenberg has produced a vital new account of one of the key episodes of the last century.”Matti Friedman, author of Spies of No Country

-

“With an eye for detail and personality quirks, Gorenberg reveals the complicated interplay between codebreakers, diplomats, and soldiers to provide a fresh account of the battle for control of Egypt in World War II.”Meredith Hindley, author of Destination Casablanca

-

“The book is a must for scholars, the text replete with many hundreds of annotated sources. For the ordinary reader it offers a thrilling spy story encompassing intelligence gleaned both from human sources and Sigint (signal intelligence) sources that played critical roles in determining the ultimate outcome of key battles for the future of the region. The style is captivating, engaging our intelligence and moving us emotionally. If you cannot fathom this or that intricate page – do not stop! Just carry on and you will be rewarded in full for your effort.”Efraim Halevy, Fathom

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use