Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

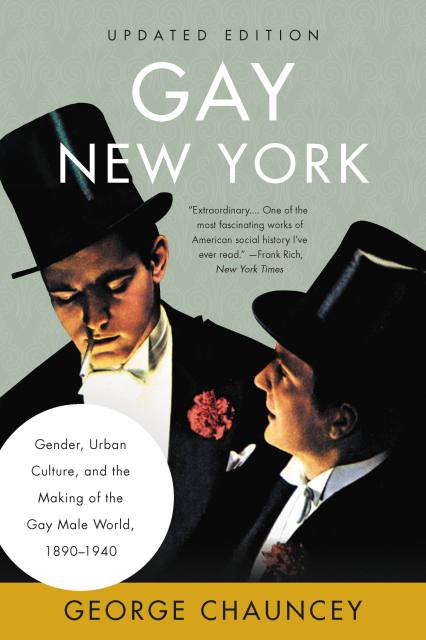

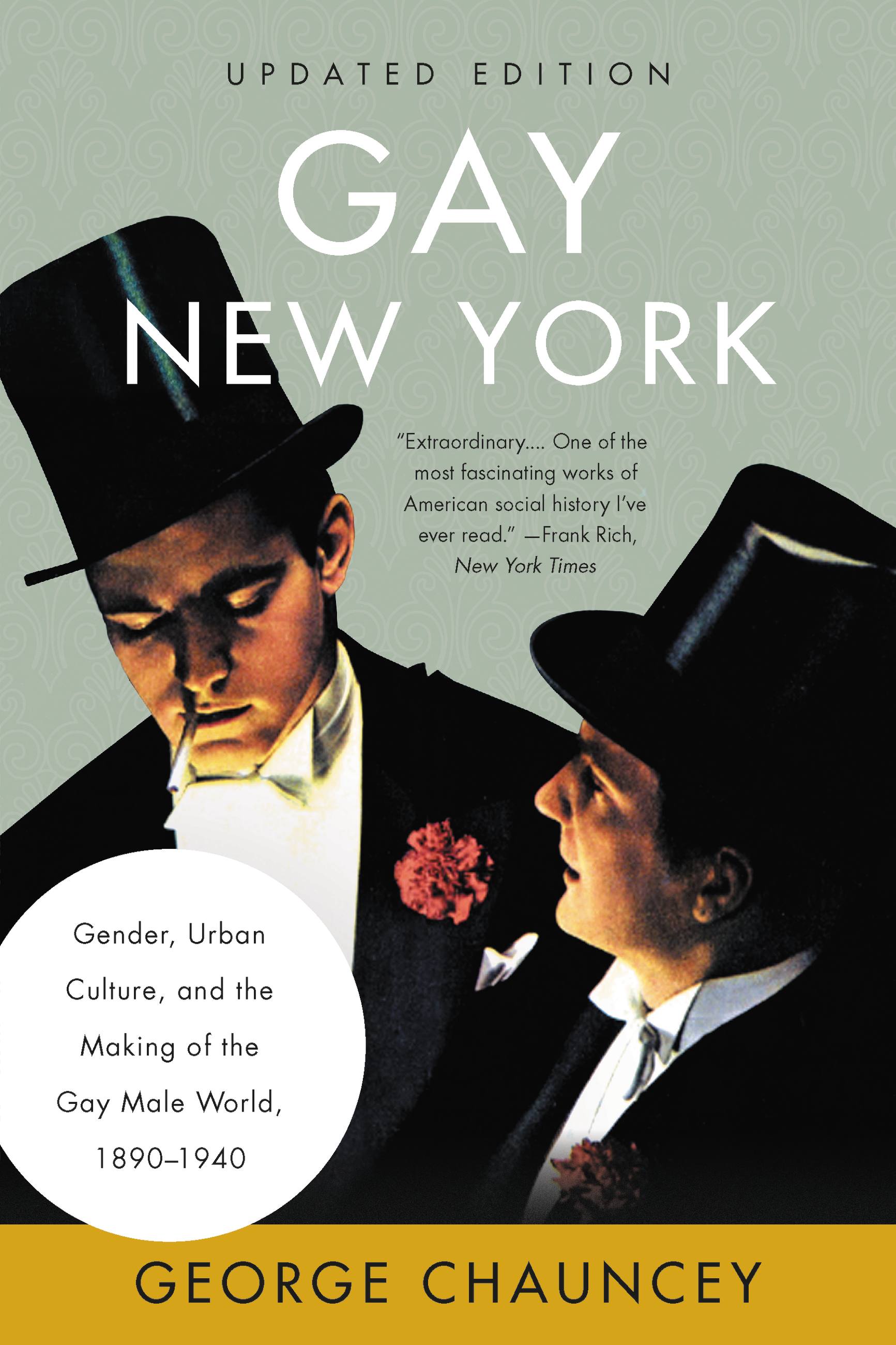

Gay New York

Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 1, 2008

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786723355

Price

$17.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 1, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Gay New York brilliantly shatters the myth that before the 1960s gay life existed in the closet, where all gay men were isolated, invisible, and ashamed. Based on years of research in diaries, letters, newspaper stories, and police reports, George Chauncey describes the saloons, speakeasies, and streets where queer men gathered; the intimate parties and immense drag balls where they celebrated; the highly visible residential enclaves they built in Greenwich Village, Harlem, and Times Square; and the complex prewar sexual culture they inhabited, which did not divide men into heterosexuals and homosexuals. It offers new perspectives on the LGBT rights revolution of our time by showing that the oppression the movement attacked in the 1960s was not unchanging, but had intensified in the 1930s as a direct response to the visibility of the prewar gay world.

Awarded the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Lambda Literary Award, and the Organization of American Historians' prize for the best first book in any field of history upon its publication in 1994, Gay New York remains a revelatory account of a long-forgotten world and the most widely taught book in American LGBT history.