By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

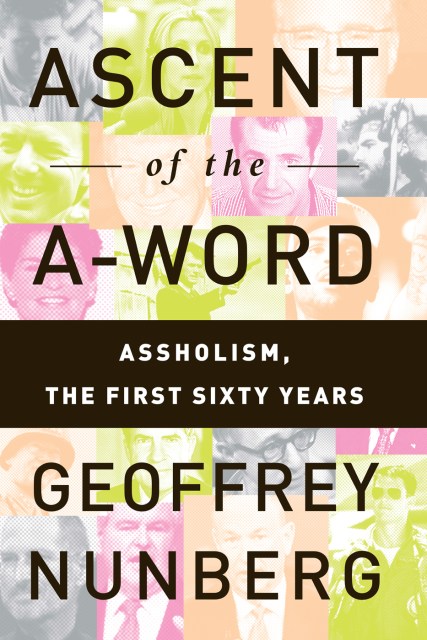

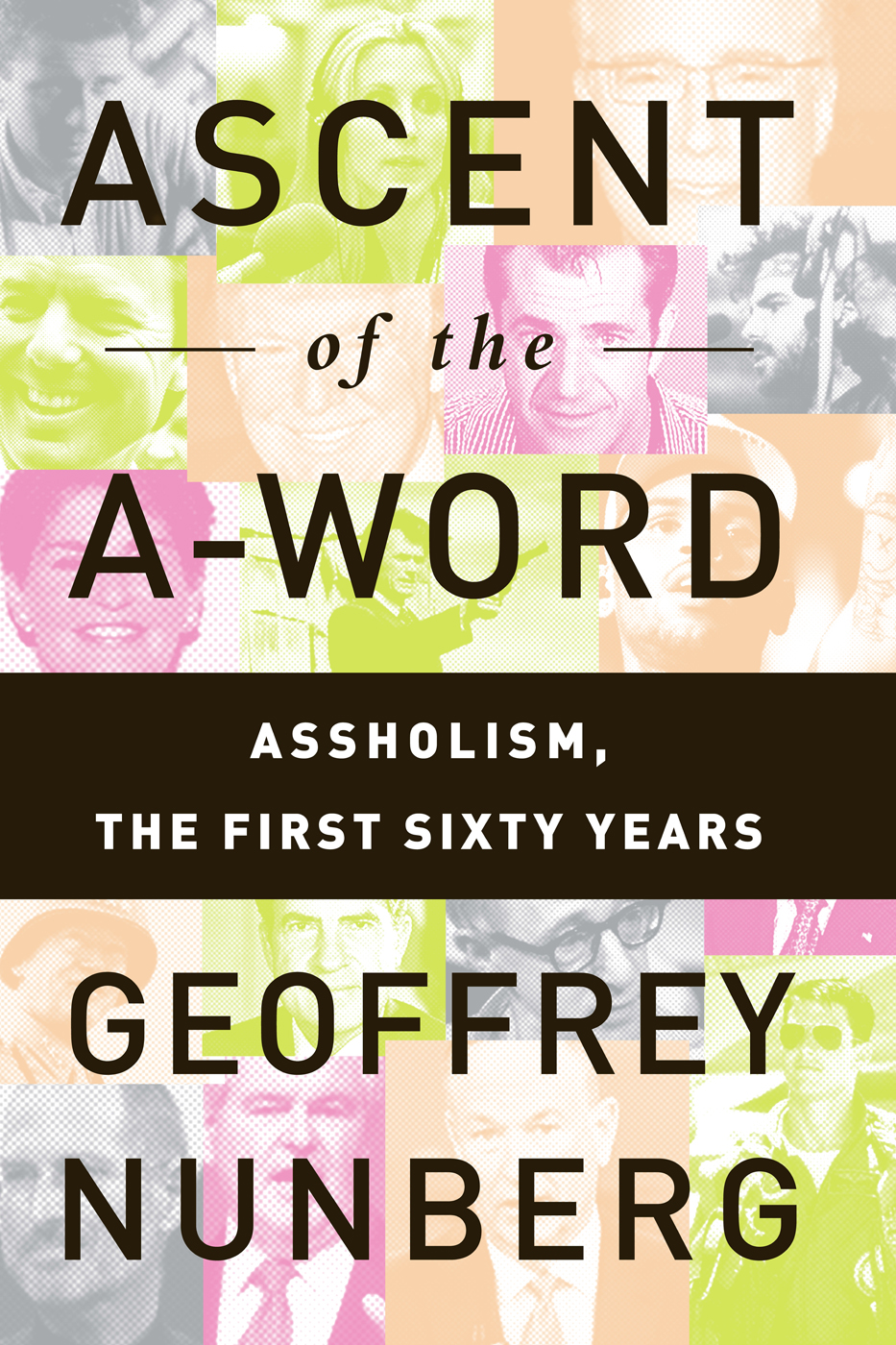

Ascent of the A-Word

Assholism, the First Sixty Years

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 14, 2012

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391764

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 14, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The asshole has become a focus of collective fascination for us, just as the phony was for Holden Caulfield and the cad was for Anthony Trollope. From Donald Trump to Ann Coulter, from Mel Gibson to Anthony Weiner, from the reality TV prima donnas to the internet trolls and flamers, assholism has become the characteristic form of modern incivility, which implicitly expresses our deepest values about class, relationships, authenticity, and fairness. We have conflicting attitudes about the A-word — when a presidential candidate unwittingly uttered it on a live mic in 2000, it confirmed to some that he was a man of the people and to others that he was a boor. But considering how much the word does for us, and to us, it hasn’t gotten nearly the attention it deserves — at least until now.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use