By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

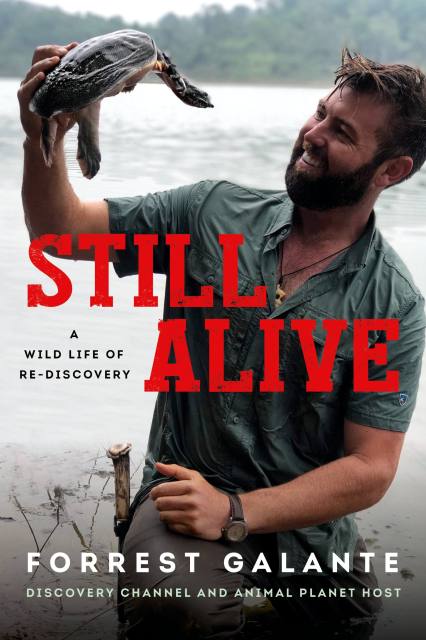

Still Alive

A Wild Life of Rediscovery

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 6, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306924255

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 6, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Experience the thrilling adventures in wildlife conservation from “the Indiana Jones of Biology” (Entrepreneur) in this action-packed and educational memoir filled with danger and intrigue.

Very few individuals can truthfully say that their work impacts every person on earth. Forrest Galante is one of them. As a wildlife biologist and conservationist, Galante devotes his life to studying, rediscovering, and protecting our planet’s amazing lifeforms. Part memoir, part biological adventure, Still Alive celebrates the beauty and determined resiliency of our world, as well as the brave conservationists fighting to save it.In his debut book, Galante takes readers on an exhilarating journey to the most remote and dangerous corners of the world. He recounts miraculous rediscoveries of species that were thought to be extinct and invites readers into his wild life: from his upbringing amidst civil unrest in Zimbabwe to his many globetrotting adventures, including suspenseful run-ins with drug cartels, witch doctors, and vengeful government officials. He shares all of the life-threatening bites, fights, falls, and jungle illnesses. He also investigates the connection between wildlife mistreatment and human safety, particularly in relation to COVID-19.

Still Alive is much more than just a can’t-put-down adventure story bursting with man-eating crocodiles, long-forgotten species rediscovered, and near-death experiences. It is an impassioned, informative, and undeniably inspiring examination of the importance of wildlife conservation today and how every individual can make a difference.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use