By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

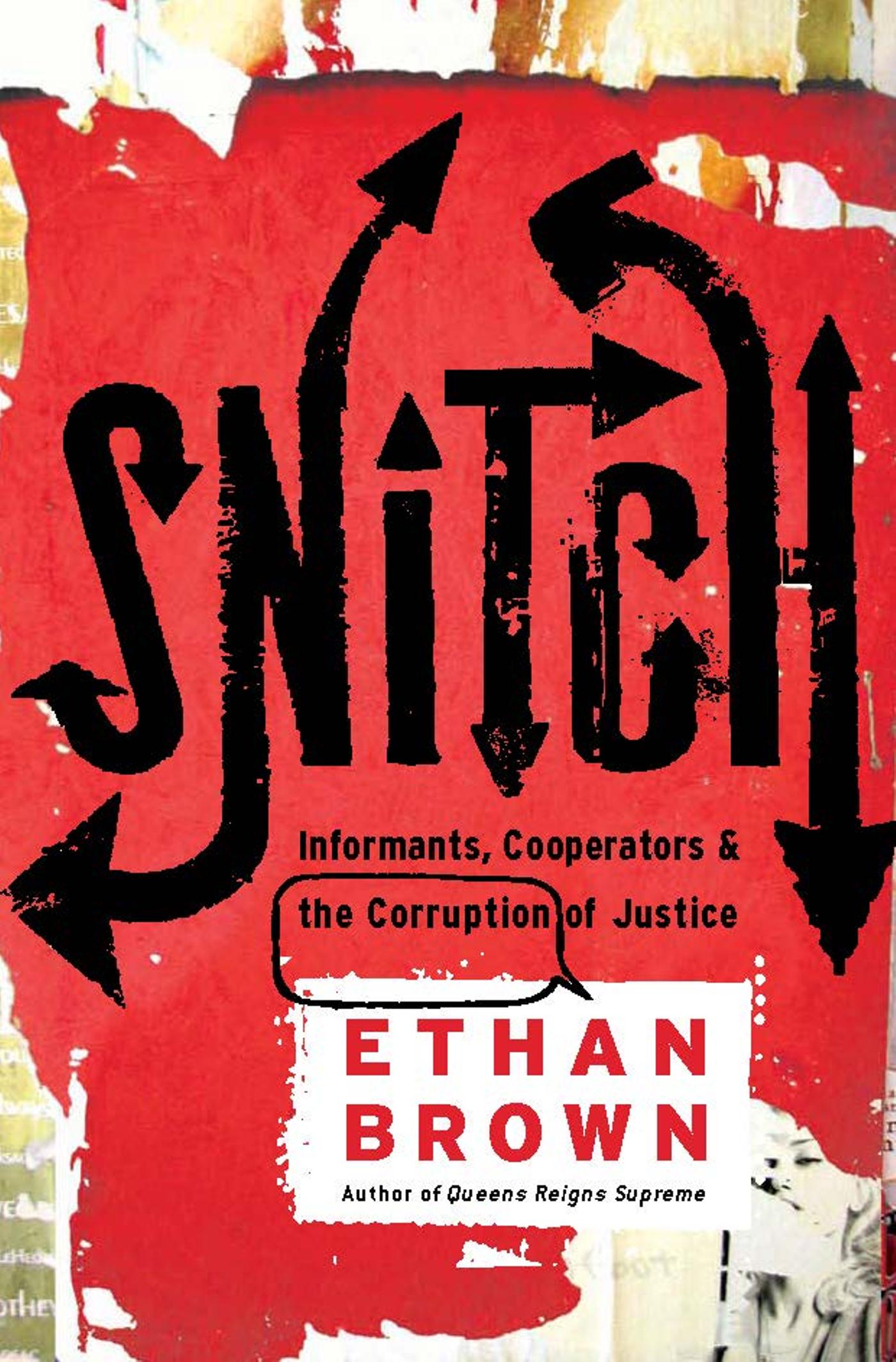

Snitch

Informants, Cooperators & the Corruption of Justice

Contributors

By Ethan Brown

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 10, 2007

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586486334

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $17.99 $22.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 10, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This cooperator-coddling criminal justice system has ignited the infamous “Stop Snitching” movement in urban neighborhoods, deplored by everyone from the NAACP to the mayor of Boston for encouraging witness intimidation. But as Snitch shows, the movement is actually a cry against the harsh sentencing guidelines for drug-related crimes, and a call for hustlers to return to “old school” street values, like: do the crime, do the time. Combining deep knowledge of the criminal justice system with frontline true crime reporting, Snitch is a shocking and brutally troubling report about the state of American justice when it’s no longer clear who are the good guys and who are the bad.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use