Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

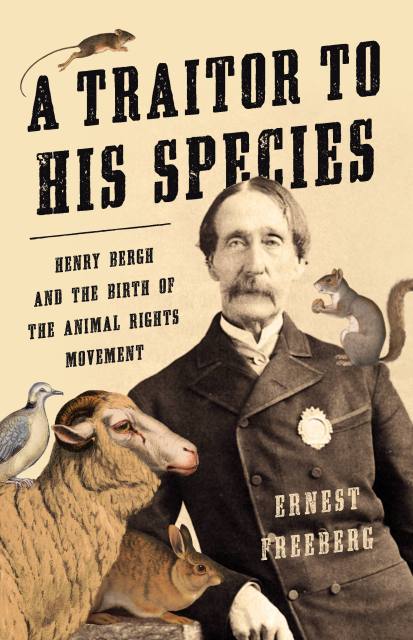

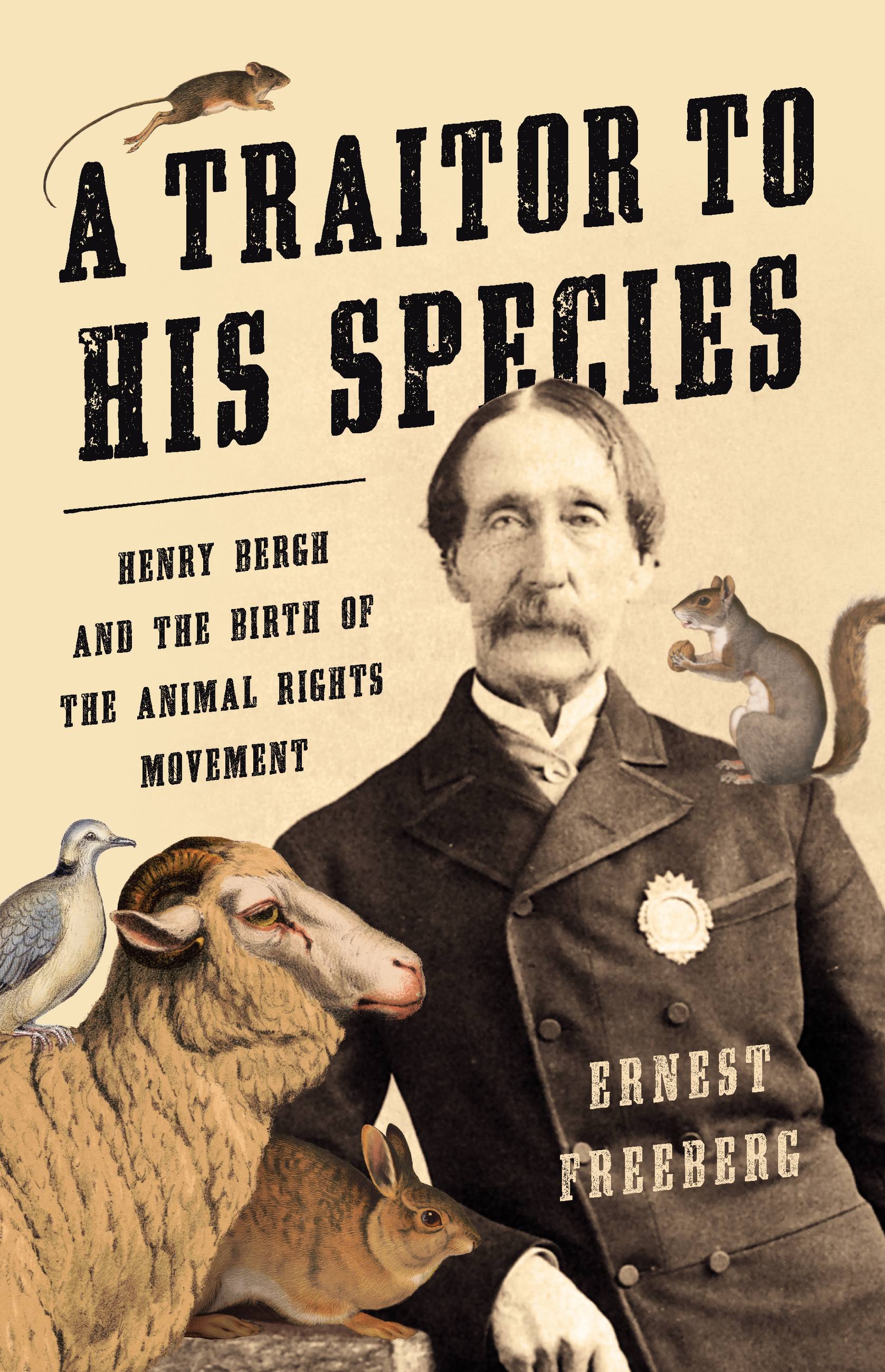

A Traitor to His Species

Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 22, 2020

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541674165

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 22, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From an award-winning historian, the outlandish story of the man who gave rights to animals.

In Gilded Age America, people and animals lived cheek-by-jowl in environments that were dirty and dangerous to man and beast alike. The industrial city brought suffering, but it also inspired a compassion for animals that fueled a controversial anti-cruelty movement. From the center of these debates, Henry Bergh launched a shocking campaign to grant rights to animals.

A Traitor to His Species is revelatory social history, awash with colorful characters. Cheered on by thousands of men and women who joined his cause, Bergh fought with robber barons, Five Points gangs, and legendary impresario P.T. Barnum, as they pushed for new laws to protect trolley horses, livestock, stray dogs, and other animals.

Raucous and entertaining, A Traitor to His Species tells the story of a remarkable man who gave voice to the voiceless and shaped our modern relationship with animals.