By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

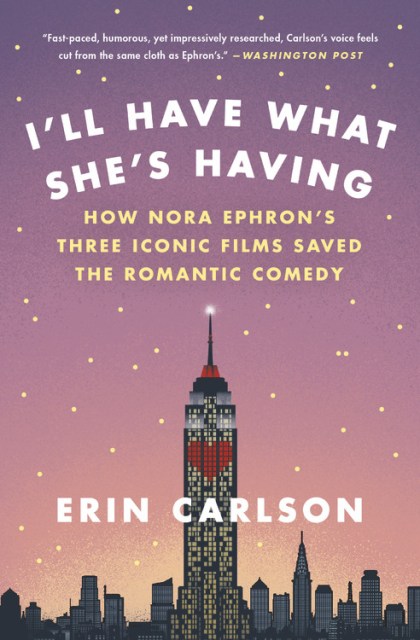

I’ll Have What She’s Having

How Nora Ephron's Three Iconic Films Saved the Romantic Comedy

Contributors

By Erin Carlson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 8, 2018

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316353892

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 8, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In I’ll Have What She’s Having entertainment journalist Erin Carlson tells the story of the real Nora Ephron and how she reinvented the romcom through her trio of instant classics. With a cast of famous faces including Rob Reiner, Tom Hanks, Meg Ryan, and Billy Crystal, Carlson takes readers on a rollicking, revelatory trip to Ephron’s New York City, where reality took a backseat to romance and Ephron–who always knew what she wanted and how she wanted it–ruled the set with an attention to detail that made her actors feel safe but sometimes exasperated crew members.

Along the way, Carlson examines how Ephron explored in the cinema answers to the questions that plagued her own romantic life and how she regained faith in love after one broken engagement and two failed marriages. Carlson also explores countless other questions Ephron’s fans have wondered about: What sparked Reiner to snap out of his bachelor blues during the making of When Harry Met Sally? Why was Ryan, a gifted comedian trapped in the body of a fairytale princess, not the first choice for the role? After she and Hanks each separatel balked at playing Mail’s Kathleen Kelly and Sleepless‘ Sam Baldwin, what changed their minds? And perhaps most importantly: What was Dave Chappelle doing . . . in a turtleneck? An intimate portrait of a one of America’s most iconic filmmakers and a look behind the scenes of her crowning achievements, I’ll Have What She’s Having is a vivid account of the days and nights when Ephron, along with assorted cynical collaborators, learned to show her heart on the screen.

-

"[Erin Carlson] offers a breezy, detailed rehearsal of three successful romantic comedies from the 1980s and '90s.... A large bag of buttery popcorn that goes down oh so pleasantly."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Deeply reported and deeply felt, Carlson's account of Nora Ephron's unlikely rise to romantic comedy queen deftly exposes the messy, human reality lurking beneath those sparkling paeans to true love. Magically nostalgic, cynical, and smart all at once."JenniferKeishin Armstrong, author of Seinfeldia and Mary and Lou andRhoda and Ted

-

"In her love letter to the rom-coms of Nora Ephron, Erin Carlson brings us on a nostalgic, insightful, and joyous ride through the legendary writer/director's most iconic works. Full of the whimsy, heartbreak, attention to detail, and romantic optimism that defined Ephron's films, I'll Have What She's Having is a must-read for anyone who is a fan of the filmmaker's genre-defining classics."Danny Strong, co-creator and executive producer of Empire

-

"Erin Carlson would make Nora Ephron proud with this deeply reported valentine to her work. Written with warmth, humor, and surprises, Carlson provides plenty of dishy insider scoop on the making of the renowned writer's beloved films. This book is the perfect companion to your favorite movie. A delicious read that will have you laughing out loud."Jo Piazza, New York Times bestselling co-author of TheKnockoff

-

"When the subject is Nora Ephron, culinary metaphors prove irresistible: Erin Carlson has cooked up a dish full of delicious insight into an icon who was both warm and snobbish,full of juicy tidbits about a feminist who preferred to hang out with the guys,a trenchant trailblazer with an old-fashioned belief in love.I'll Have What She's Having offers a satisfying portrait of a lady who wasn't always 'nice' but who nevertheless created timeless moments to fill our hearts and give us hopeFaith Salie,author of Approval Junkie and contributor to CBS Sunday Morning

-

"Erin Carlson has served up a lively, inside look at the making of Nora Ephron's three famous rom-coms and how she broke into the male-dominated directing club. Anyone who loves Nora and her films will relish this book."Lynn Povich, authorof The Good Girls Revolt

-

"Read this book in an adorable bookshop and, who knows, maybe you'll meet-cute with a handsome stranger reading the same book. Of course, if he's reading a book about Nora Ephron rom-coms, he may be gay. Ugh, that is sooo your luck, Carol! Also, it's raining now and you're wearing suede."Meredith Scardino,writer for Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, The Colbert Report, thisbook blurb

-

"Perky and approachable . . . those who miss funny romantic comedies will enjoy this detailed behind-the-scenes look at three of the best."Library Journal

-

"Carlson's first book pays affectionate and clear-eyed tribute to the three most popular movies associated with screenwriter and director Nora Ephron. Going behind the scenes to explore the making of When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle, and You've Got Mail, she dispenses insider information that fans of the movies will find hard to resist ... her breezy, frisky tone makes reading the book like sharing a gossipy lunch with an old friend. Although she keeps the focus on the three films, she also allows herself to go off on fascinating tangents about the lives and other movies of the director and her stars. As sweet and bubbly a treat as the movies it covers, this book does what it does impeccably, and readers will love it."Booklist

-

"I'll Have What She's Having: How Nora Ephron's Three Iconic Films Saved the Romantic Comedy delivers a delight of buzzy Hollywood backstories unearthed by veteran entertainment journalist Erin Carlson. The book also serves as a tribute . . . Hanks, Ryan, Rob Reiner and a host of others provided fresh interviews about Ephron, with great results."New York Daily News

-

"Fast-paced, humorous, yet impressively researched, Carlson's voice feels cut from the same cloth as Ephron's . . . Seamlessly woven into the narrative are bits of behind-the-scenes gossip that will surprise even the most die-hard fans. . . . The book's wide net of sources, along with Ephronisms and movie dialogue, proves to be a wonderful recipe, giving readers a sense of what it was like working on an Ephron project at every level."Washington Post

-

"The rom-com is having a moment. But the case Erin Carlson makes in I'll Have What She's Having is solid: Nora Ephron reinvented and saved the genre with When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle and You've Got Mail. . . . ultimately, the book serves to show how the movies were made and the effect they had."Los Angeles Times

-

"This smart and witty book is as much about the life and times of the brilliant Nora Ephron as it is her three great late-20th-century rom-coms: When Harry Met Sally (1989), Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and You've Got Mail (1998), with Meg Ryan standing in for Everywoman in all three. This is an excellent piece of Hollywood scholarship, thoughtful and entertaining. Make no mistake: It's not a love letter to Nora. Just like Ephron, writer Erin Carlson wields a sharp pen."Toronto Star

-

"An enjoyable ride through the years Ephron spent behind the camera. . . . What Carlson effectively creates is a persuasive time capsule of a filmmaker who believed a connection of the heart was born of a soulful, searing, satisfying tête-à-tête between two equals."USA Today

-

"Reading author Erin Carlson's book I'll Have What She's Having is as satisfying as finding out what goes into a favorite dessert--and then having another slice."Associated Press

-

"She shows Ephron's evolution as a filmmaker and gets down to the details of how the rom-com sausage is made. . . . The book's wide net of sources, along with Ephronisms and movie dialogue, proves to be a wonderful recipe, giving readers a sense of what it was like working on an Ephron project at every level. Seamlessly woven into the narrative are bits of behind-the-scenes gossip that will surprise even the most die-hard fans. . . . Fast-paced, humorous, yet impressively researched, Carlson's voice feels cut from the same cloth as Ephron's."San Antonio Express News

-

"Erin Carlson depicts the stubborn ferocity that equipped Nora Ephron to crack Hollywood in I'll Have What She's Having."Toronto Star

-

"Ms. Carlson tells a full, gossipy "behind the scenes" tale of Ephron's stylish and witty world of film."TheWall Street Journal

-

"When Harry Met Sally and other Nora Ephron films finally get the star treatment they deserve in I'll Have What She's Having. Erin Carlson interviews dozens of people involved in the filmmaking for an intimate, insightful look at some great romantic comedies."Campus Circle

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use