By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

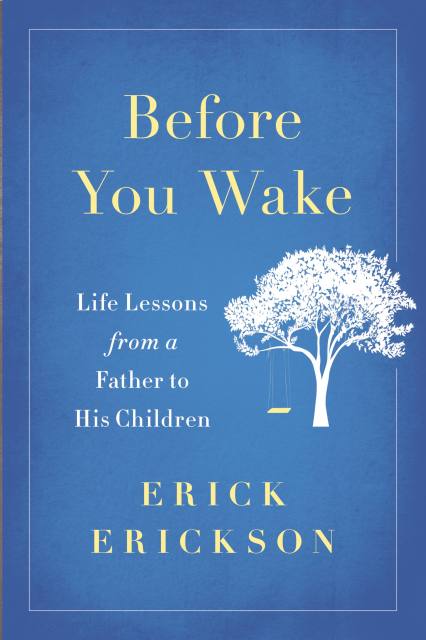

Before You Wake

Life Lessons from a Father to His Children

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780316439541

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $20.00 $26.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A must read.” — RedState

In late 2016, prompted by the news that his wife was battling cancer and his own pulmonary medical scare, Erick Erickson posted a piece to his website, The Resurgent. Styled as a letter to his young children, the piece, titled “If I Should Die Before You Wake,” was a stirring message–and challenge–about how to live a life of purpose and joy. The essay went viral, shared by figures like New York Times columnist and author of The Road to Character, David Brooks. Now, in a time when our country needs healing and a reminder of our values more than ever, Erickson has expanded the project, composing a total of ten letters, featuring a wonderful mix of the practical, inspirational, and spiritual.

-

"A must read: Erick Erickson's Before You Wake is a heartfelt reminder of what's important."RedState

-

"Poignant.""The Daily Briefing," Fox News

-

"Striking ... Reading [Erickson's] personal story is a small experiment in weakening the filter, in shaking off the spell of simulated life, of letting a person's suffering give you a glimpse of them in full."Ross Douthat, New York Times

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use