Promotion

Use code BEST25 for 25% off storewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

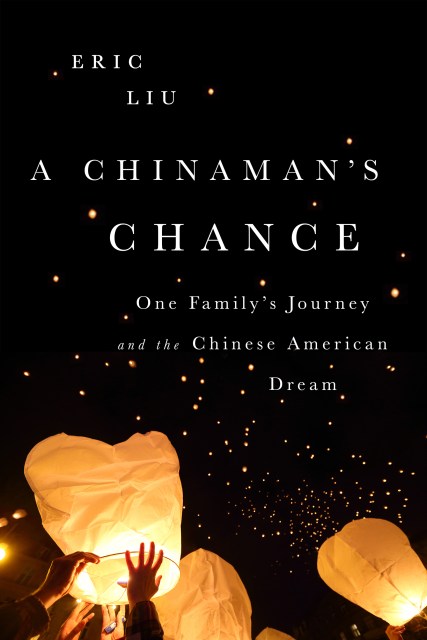

A Chinaman’s Chance

One Family's Journey and the Chinese American Dream

Contributors

By Eric Liu

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 8, 2014

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391955

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 8, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In many ways, Chinese Americans today are exemplars of the American Dream: during a crowded century and a half, this community has gone from indentured servitude, second-class status and outright exclusion to economic and social integration and achievement. But this narrative obscures too much: the Chinese Americans still left behind, the erosion of the American Dream in general, the emergence — perhaps — of a Chinese Dream, and how other Americans will look at their countrymen of Chinese descent if China and America ever become adversaries. As Chinese Americans reconcile competing beliefs about what constitutes success, virtue, power, and purpose, they hold a mirror up to their country in a time of deep flux.

In searching, often personal essays that range from the meaning of Confucius to the role of Chinese Americans in shaping how we read the Constitution to why he hates the hyphen in “Chinese-American,” Eric Liu pieces together a sense of the Chinese American identity in these auspicious years for both countries. He considers his own public career in American media and government; his daughter’s efforts to hold and release aspects of her Chinese inheritance; and the still-recent history that made anyone Chinese in America seem foreign and disloyal until proven otherwise. Provocative, often playful but always thoughtful, Liu breaks down his vast subject into bite-sized chunks, along the way providing insights into universal matters: identity, nationalism, family, and more.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use