By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

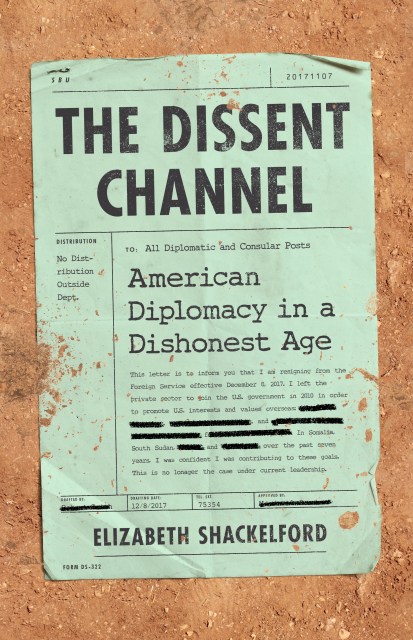

The Dissent Channel

American Diplomacy in a Dishonest Age

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 12, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541724471

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 12, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A young diplomat’s account of her assignment in South Sudan, a firsthand example of US foreign policy that has failed in its diplomacy and accountability around the world.

In 2017, Elizabeth Shackelford wrote a pointed resignation letter to her then boss, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. She had watched as the State Department was gutted, and now she urged him to stem the bleeding by showing leadership and commitment to his diplomats and the country. If he couldn’t do that, she said, “I humbly recommend that you follow me out the door.”

With that, she sat down to write her story and share an urgent message.

In The Dissent Channel, former diplomat Elizabeth Shackelford shows that this is not a new problem. Her experience in 2013 during the precarious rise and devastating fall of the world’s newest country, South Sudan, exposes a foreign policy driven more by inertia than principles, to suit short-term political needs over long-term strategies.

Through her story, Shackelford makes policy and politics come alive. And in navigating both American bureaucracy and the fraught history and present of South Sudan, she conveys an urgent message about the devolving state of US foreign policy.

In 2017, Elizabeth Shackelford wrote a pointed resignation letter to her then boss, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. She had watched as the State Department was gutted, and now she urged him to stem the bleeding by showing leadership and commitment to his diplomats and the country. If he couldn’t do that, she said, “I humbly recommend that you follow me out the door.”

With that, she sat down to write her story and share an urgent message.

In The Dissent Channel, former diplomat Elizabeth Shackelford shows that this is not a new problem. Her experience in 2013 during the precarious rise and devastating fall of the world’s newest country, South Sudan, exposes a foreign policy driven more by inertia than principles, to suit short-term political needs over long-term strategies.

Through her story, Shackelford makes policy and politics come alive. And in navigating both American bureaucracy and the fraught history and present of South Sudan, she conveys an urgent message about the devolving state of US foreign policy.

-

"An honest accounting by a patriot seeking a deliberate national discourse on what actually makes America great."Kirkus Reviews

-

"The Dissent Channel represents an important read for those seeking to reckon with the longer-term shortcomings of American foreign policy, particularly as they concern South Sudan."Global Policy Journal

-

"Her keen and empathetic eye brings into sharp relief the disastrous consequences of derelict foreign policy against the brutal backdrop of a fledgling, war-torn country."Seven Days VT

-

"Shackleford's book is a damning chronicle of the naivety and gullibility of Western governments. Rather than making good on their expressions of concern, they continued to pour money into South Sudan."Independent Catholic News

-

"At a time when many Americans are wondering if a values-based foreign policy is either desirable or feasible, Elizabeth Shackelford offers a passionate and detailed account of the risks of not having one, under the challenging circumstances faced by the Obama Administration in South Sudan. In presenting one side of a complex story, Elizabeth reveals why it is imperative now more than ever that dissenting voices, particularly from those closest to the ground, be heard and answered"Anne-Marie Slaughter, CEO, New America

-

"In these norm-shattering times, we urgently need to examine and learn from mistakes of the past. This beautifully written, personal story exposes uncomfortable truths about the costs of America's foreign policy approach and, without cynicism, offers some hope for a better way forwardYara Bayoumy, National SecurityEditor, The Atlantic

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use