Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

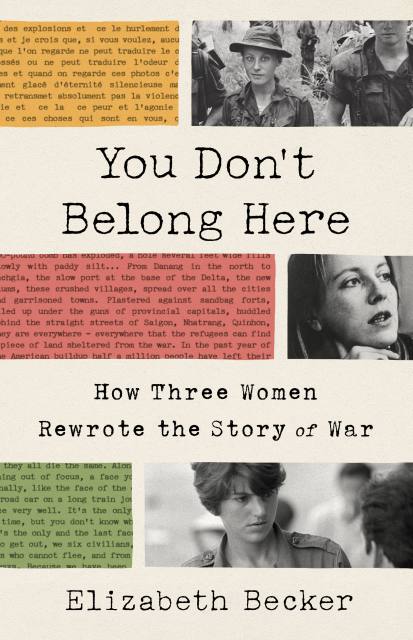

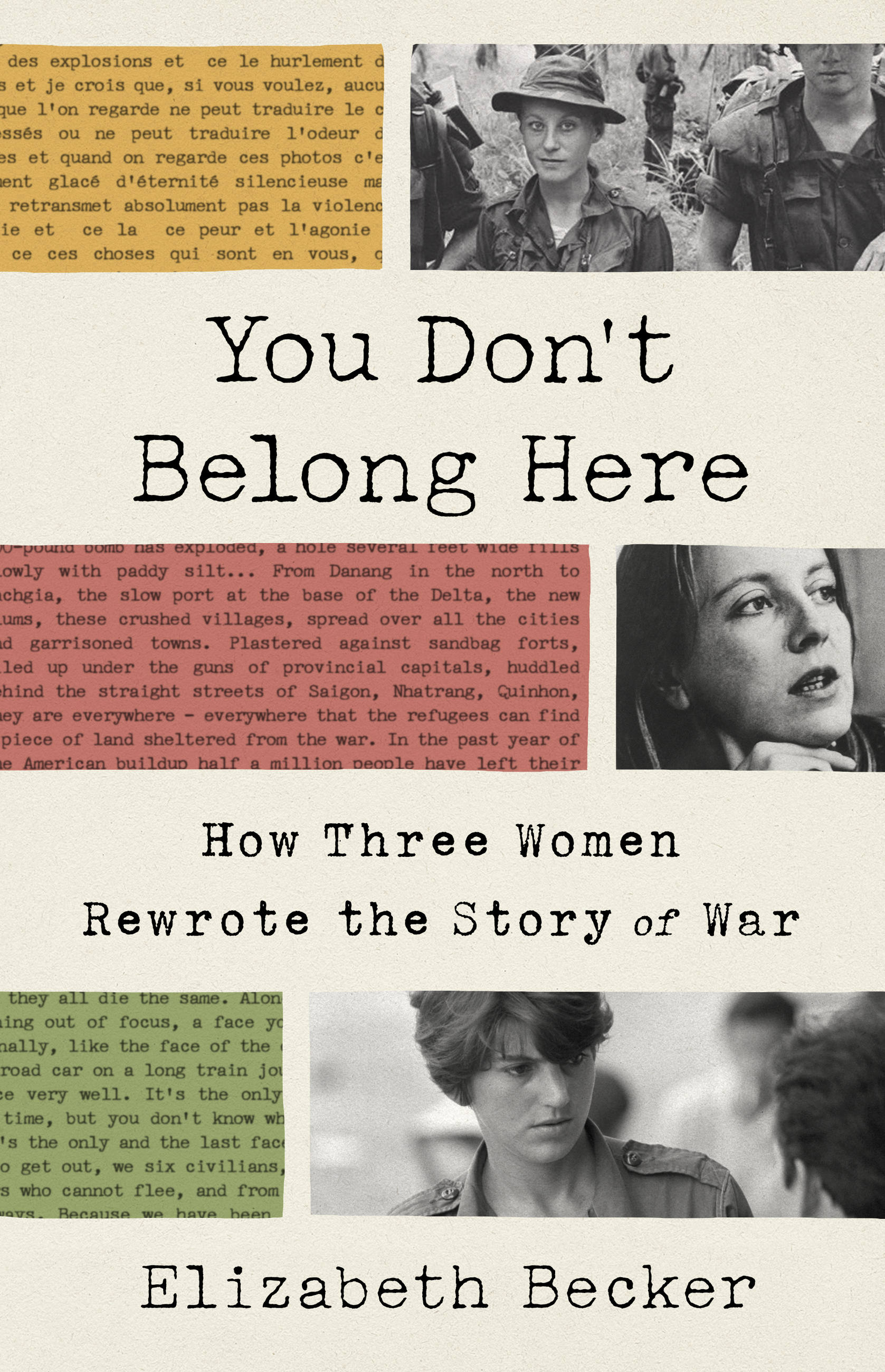

You Don’t Belong Here

How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 22, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541768239

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 22, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

WINNER OF THE 2022 GOLDSMITH BOOK PRIZE

WINNER OF THE 2022 SPERBER PRIZE

The long buried story of three extraordinary female journalists who permanently shattered the official and cultural barriers to women covering war.

WINNER OF THE 2022 SPERBER PRIZE

The long buried story of three extraordinary female journalists who permanently shattered the official and cultural barriers to women covering war.

Kate Webb, an Australian iconoclast, Catherine Leroy, a French dare devil photographer, and Frances FitzGerald, a blue-blood American intellectual, arrived in Vietnam with starkly different life experiences but one shared purpose: to report on the most consequential story of the decade.

At a time when women were considered unfit to be foreign reporters, Frankie, Catherine and Kate paid their own way to war, arrived without jobs, challenged the rules imposed on them by the military, ignored the belittlement and resentment of their male peers and found new ways to explain the war through the people who lived through it.

In You Don’t Belong Here, Elizabeth Becker uses these women’s work and lives to illuminate the Vietnam War from the 1965 American buildup, through the Tet Offensive, the expansion into Cambodia, the American defeat and its aftermath. Arriving herself in the last years of the war, Elizabeth writes as an historian and a witness to what these women accomplished.

What emerges is an unforgettable story of three journalists forging their place in a land of men, often at great personal sacrifice, and forever altering the craft of war reportage for generations. Deeply reported and filled with personal letters, interviews, and profound insight, You Don’t Belong Here fills a void in the history of women and of war.

-

“Becker not only shines a light on the contributions of those correspondents — along with the risks they took to show and tell the raw truths of the war as they saw it — but provides a valuable depth of cultural and historical insight into the conflict…There is a fourth woman who rewrote the story of war, and that is of course Elizabeth Becker, who with a depth of research and an abundance of grace gives fresh insight into the background and achievements of three extraordinary war correspondents — and the price they paid for the intensity of their work…“You Don’t Belong Here” is deserving of a wide readership. My guess is that every young woman filled with journalistic ambition will have a copy in her backpack, perhaps as she ventures into a war zone with her laptop, her satellite phone and a sustaining dose of idealism.”Washington Post

-

“With controlled anger, in a riveting narrative… Becker conveys the particular sacrifices that these three women had to make: the indignities, the psychological cost, the elusiveness of stable relationships and children. Still, it’s exhilarating to read Becker’s account of how these women overcame the narrow definitions of their early lives and found themselves by surrendering to the extreme demands of reporting a war.”The Atlantic

-

“Compelling… Becker’s book does an excellent job of bringing back what my colleague in Bosnia, the New York Times reporter John F. Burns, once nostalgically called ‘that time, that place, of war.’ She writes beautifully of the heartache the women suffer, their struggles to be taken seriously, the guffaws, the catcalls, the daily small humiliations that amounted to the French photographer’s fierce indictment: You don’t belong here.”Janine di Giovanni, Foreign Policy

-

“A prize-worthy page-turner of tension, suspense and drama. The tone of the book intensifies with each chapter…Becker never loses sight of her goal to illuminate these women in the larger context of America’s biggest foreign policy disaster of the 20th century.”Mike Tharp, Asia Times

-

“An incisive history of the Vietnam War via the groundbreaking accomplishments of three remarkable women journalists…. A deft, richly illuminating perspective on the Vietnam War.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“An absorbing narrative… Included are gripping stories of Webb's and Becker's coverage of Cambodia's bloody killing fields, and Webb's three-week imprisonment by the North Vietnamese… Readers interested in the Vietnam War and in women's history will be engaged.”Library Journal

-

“You Don’t Belong Here provides a fresh perspective not just on how the Second Indochina War was reported, but also on how it can be narrated through the lives of those who witnessed it. In writing it, Becker has made a significant contribution to the history of women in journalism and women in war.”Mekong Review

-

“You Don’t Belong Here is a significant contribution to the history of both the Vietnam War and women in journalism.”Bookpage

-

“Crisp and incisive… Becker, who also reported from Cambodia in the 1970s, fluidly sketches the history and politics of the Vietnam War and captures her subjects in all their complexity. Readers interested in women’s history and foreign affairs won’t be able to put this fascinating chronicle down.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Becker blends [the journalists’] individual stories with wider history, setting the unfolding tragedy in Vietnam in the background as her protagonists develop doubts about the logic and legitimacy of the war. She provides vivid accounts of their journalistic exploits and tales of how they suffered in their work—their injuries, traumas, excessive drinking, and complicated affairs.”Foreign Affairs

-

“Whether as a woman’s story or a war story, this should find a wide audience.”Booklist

-

"Elizabeth Becker resurrects the long-forgotten stories and enormous sacrifices made by a generation of women who paved the way for the rest of us. Elegant, angry and utterly engaging, it is a long overdue story about a small band of courageous and visionary women.You Don’t Belong Here is a masterpiece of a book."Rachel Louise Snyder, author of No Visible Bruises

-

“ A riveting read with much to say about the nature of war and the different ways men and women correspondents cover it. Frank, fast-paced, often enraging, “You Don’t Belong Here” speaks to the distance traveled and the journey still ahead.”Geraldine Brooks, Pulitzer Prize winning author of MARCH, former Wall Street Journal foreign correspondent