By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

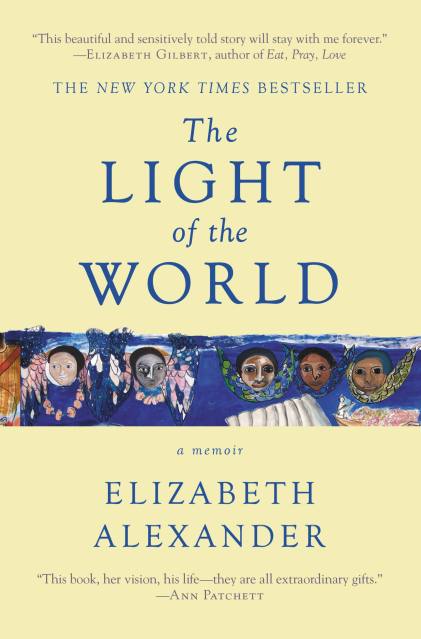

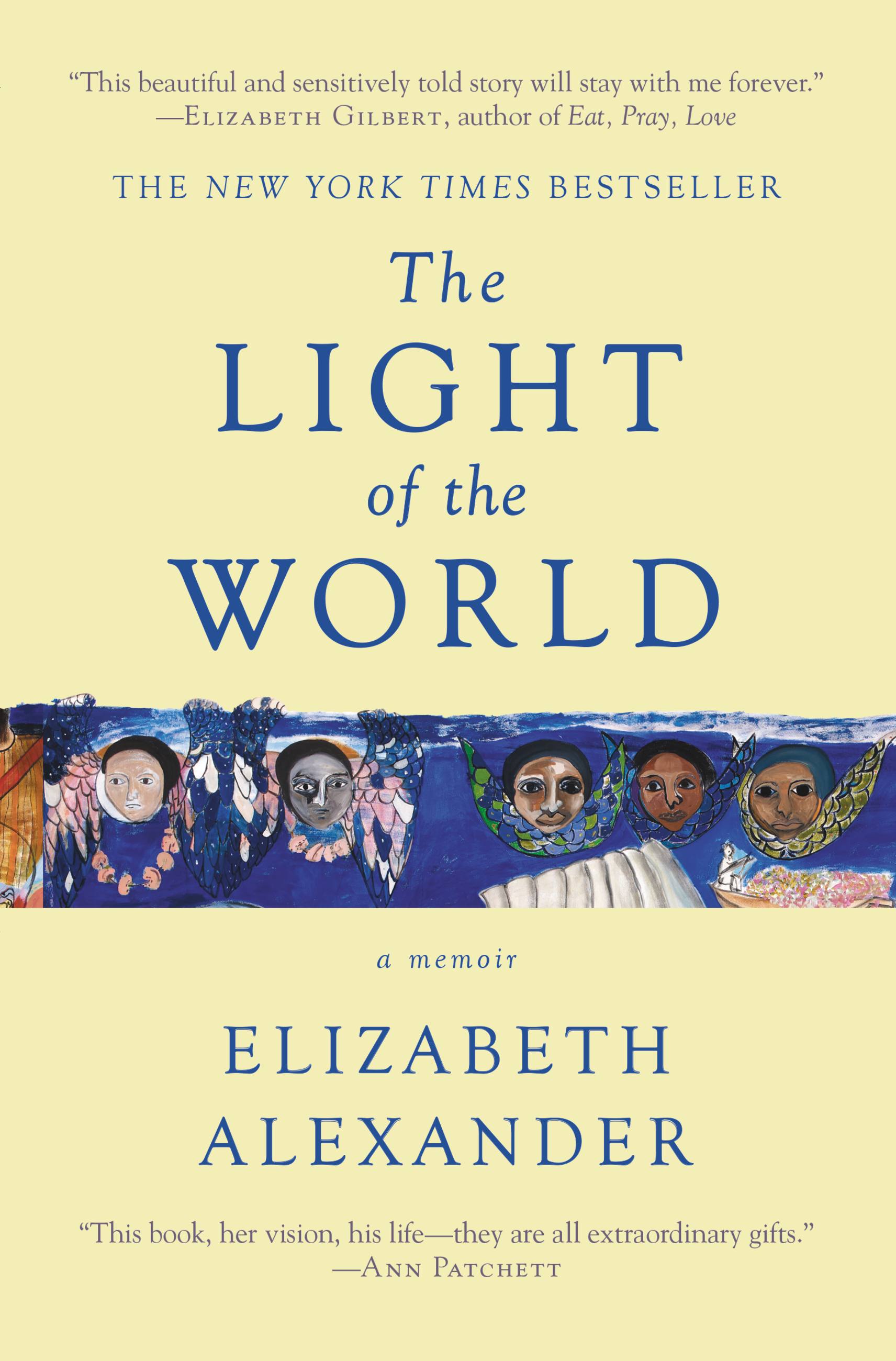

The Light of the World

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 21, 2015

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455599851

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $34.00 $44.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 21, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A deeply resonant memoir for anyone who has loved and lost, from acclaimed poet and Pulitzer Prize finalist Elizabeth Alexander.

In The Light of the World, Elizabeth Alexander finds herself at an existential crossroads after the sudden death of her husband. Channeling her poetic sensibilities into a rich, lucid price, Alexander tells a love story that is, itself, a story of loss. As she reflects on the beauty of her married life, the trauma resulting from her husband’s death, and the solace found in caring for her two teenage sons, Alexander universalizes a very personal quest for meaning and acceptance in the wake of loss.

The Light of the World is at once an endlessly compelling memoir and a deeply felt meditation on the blessings of love, family, art, and community. It is also a lyrical celebration of a life well-lived and a paean to the priceless gift of human companionship. For those who have loved and lost, or for anyone who cares what matters most, The Light of the World is required reading.

In The Light of the World, Elizabeth Alexander finds herself at an existential crossroads after the sudden death of her husband. Channeling her poetic sensibilities into a rich, lucid price, Alexander tells a love story that is, itself, a story of loss. As she reflects on the beauty of her married life, the trauma resulting from her husband’s death, and the solace found in caring for her two teenage sons, Alexander universalizes a very personal quest for meaning and acceptance in the wake of loss.

The Light of the World is at once an endlessly compelling memoir and a deeply felt meditation on the blessings of love, family, art, and community. It is also a lyrical celebration of a life well-lived and a paean to the priceless gift of human companionship. For those who have loved and lost, or for anyone who cares what matters most, The Light of the World is required reading.

-

"THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD simply took my breath away."First Lady Michelle Obama, MORE

-

"This is a beautifully written, heartrendingly candid account of the abrupt loss of her husband by the distinguished poet Elizabeth Alexander. It is a vivid, intensely rendered elegy of a remarkable man--husband, father, artist, chef. Both a memoir and a portrait of a marriage, THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is, as its title suggests, a bittersweet testament to love and the memory of love, one of the most compelling memoirs of loss that I have ever read."Joyce Carol Oates

-

"Elizabeth Alexander has written a brave and beautiful book about love and loss-the deep pain that comes with such a loss, and the redemptive realization that such pain is a small price to pay for such a love."Jeannette Walls, New York Times bestselling author of The Glass Castle

-

"This is a gorgeous love story, written by one of America's greatest contemporary poets. Graceful in its simplicity, sweeping in scope, this book is proof that behind the boarded up windows of America's roiled marriages and ruined affairs, true love still exists, and where it does exist, it graces the world-and us-with light and hope. Elizabeth Alexander is a prose writer of deep talent and affecting skill. With ease, she peels back layer after layer to show the soft secrets of affection, the kindness, and the wide open generosity of a full hearted man and talented artist, who had more love to give in his relatively short lifetime than most of us will ever know."James McBride, National Book Award-winning author of The Good Lord Bird and #1 New York Times bestseller The Color of Water

-

"Remarkably uplifting."The Washington Post

-

"She shows us how feeding your family and remembering to be aware of the small details of everyday life are the bedrocks of true connection. In this book of prose, each page is a poem."O, The Oprah Magazine

-

"It is both raw and exquisitely crafted, mercilessly direct and sometimes lavishly metaphorical... THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is, quite simply, a miracle."Boston Sunday Globe

-

"THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is crushing, lovely, painful, and above all powerful. It is difficult to believe that anyone who has suffered loss will remain unaffected by this marvelous book."New York Journal of Books

-

"[An] elegantly drawn memoir."Los Angeles Times Book Review

-

"THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is as beautiful and moving as a gorgeous piece of music. The minute I finished it, I longed to read it again."Anna Deavere Smith

-

"A radiant book of love's everlastingness and art's infinite sustenance."Booklist (starred review)

-

"An elegy that records, in hypnotic waves of love and grief."New York Times, T Magazine

-

"In THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD, Alexander discovers a warmth that will remind some readers of the deeper truth of grieving: It is a sign of love."New York Times Book Review

-

"[A] gorgeous and intimate tribute."Newsday

-

"Feel[s] authentic and true."The Economist

-

"A deeply intimate and lyrical portrait."Essence

-

"In art, in poetry and in her community of friends and family, Alexander finds divinity. The memoir itself is, of course, art. Its eloquent, grief-struck gratitude draws the reader in, and we celebrate and mourn alongside Alexander."Miami Herald

-

"THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is a celebration of life, a portrait of grief, and a lesson in the healing power of memory."KMUW

-

"[Elizabeth Alexander] is gifted with an incredible ability to put words to meter and create profound meaning."The Root

-

"This memoir is a celebration of love, life, books, family, food and friends. Reading THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is like reading an extended narrative poem, the main character, though dead, is fully alive on the page. This is more elegy than memoir, a tribute to her husband's memory-her memories of him with her."Tallahassee Democrat

-

"Like a poem, so carefully has each word, each sentence, been chosen and polished."Entertainment Weekly

-

"[In THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD, Elizabeth Alexander] tells a love story that is, itself, a story of loss."WAMC Northeast Radio

-

"The book is a testament to ardor, and also to profound loss."Valley News

-

"The poet's answer to her husband's death is spiritual and ethical."Editors' Choice, New York Times

-

"THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is an absolutely luminous read, the kind full of incompressible dimension best experienced in its totality."Brain Pickings

-

"Beautiful, warm, lyrical, honest and reverent, THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is a loving tribute to a much-loved husband, and to the strength, tenacity and determination of the wife left behind."Winnipeg Free Press

-

"Alexander relays the story of her husband's sudden death and how her grief affected her. Using her gift for words, however, she was able to find meaning in her loss"BookReporter

-

"THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD is a tale of beautiful people who made a beautiful life together-a life of delicious food, fresh flowers, music, and friends."Los Angeles Review of Books

-

"Accomplished poet Elizabeth Alexander paints the lush details of a life well-lived in her memoir, THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD."The Charlotte Observer

-

"[A] deeply touching memoir."GOOP

-

"A powerfully poetic testament to living on through those we loved."Family Circle

-

"This is a compelling memoir, told through a poetic voice that blends prose and poetry as Alexander details the death, the loss and the grief that she and her sons experience."Neworld Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use