Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

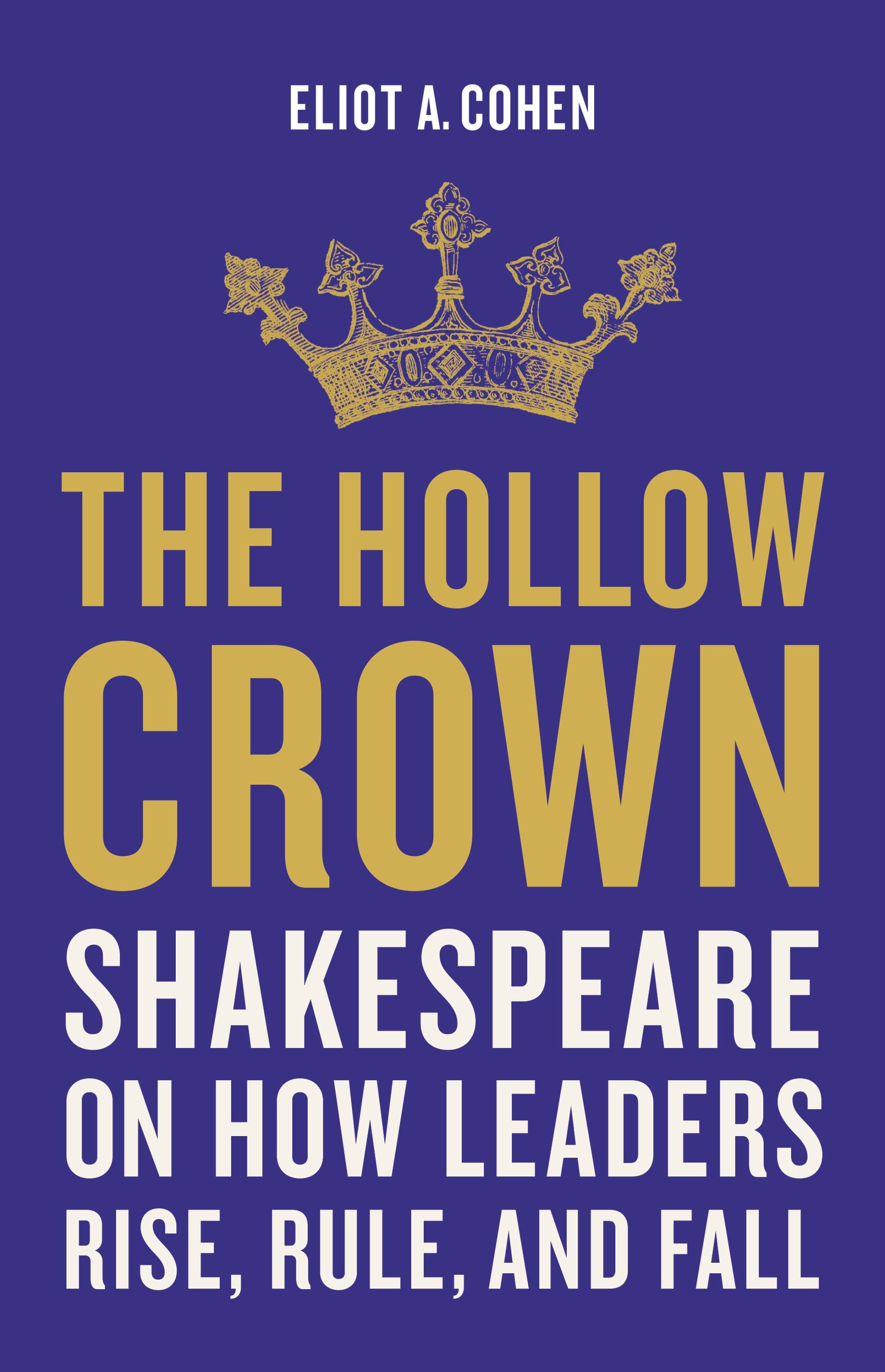

The Hollow Crown

Shakespeare on How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 24, 2023

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541644861

Price

$30.00Price

$39.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 24, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

William Shakespeare understood power: what it is, how it works, how it is gained, and how it is lost.

In The Hollow Crown, Eliot A. Cohen reveals how the battling princes of Henry IV and scheming senators of Julius Caesar can teach us to better understand power and politics today. The White House, after all, is a court—with intrigue and conflict rivaling those on the Globe’s stage—as is an army, a business, or a university. And each court is full of driven characters, in all their ambition, cruelty, and humanity. Henry V’s inspiring speeches reframe John F. Kennedy’s appeal, Richard III’s wantonness illuminates Vladimir Putin’s brutality, and The Tempest’s grace offers a window into the presidency of George Washington.

An original and incisive perspective, The Hollow Crown shows how Shakespeare’s works transform our understanding of the leaders who, for good or ill, make and rule our world.

Genre:

-

“The Hollow Crown is a thoroughly readable and enjoyable survey of some of Shakespeare’s finest work… Cohen’s book will shed light on history and literature while provoking thought about how to read and how to operate today.”Washington Examiner

-

“A compelling new book.”American Purpose

-

“A book that will appeal to anyone who recognizes in Shakespeare’s casts of characters our common, complex humanity, necessarily political but not consummately so, usually not happily political, and not ever one-sidedly political, either.”The Dispatch

-

“An intriguing and compact volume that’s very much worth reading for Shakespeare aficionados and political junkies alike.”The Liberal Patriot

-

“Cohen’s compelling and powerful book, The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare on How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall, is a superb primer on Shakespeare, especially his perspective on human character and political power.”Washington Diplomat

-

“Lawyers and judges devote a lot of attention to literature, leadership and power, and for those inclined, Eliot Cohen’s recent book is highly recommended.”Law.com

-

“The Hollow Crown effectively explores Shakespeare’s political insights into how leaders evolve… Cohen’s prose is also a delight.”The US Army War College Quarterly

-

“A thoughtful consideration of the complexities of power.”Kirkus

-

“In The Hollow Crown, Dr. Eliot A. Cohen blends his deep knowledge of Shakespeare with his decades of senior experience in public service and academia to produce a unique and compelling look at how Shakespeare’s themes about power and leadership continue to recur throughout history. Whether looking at unchecked ambition and the corrupting nature of power seen in Macbeth and Richard III, the manipulation and deception of Iago, or the integrity and moral clarity of Brutus, Dr. Cohen finds striking parallels throughout different chapters of American and world history. Cohen is one of the rare people who (like Hamlet) can rightly claim to be a man of thought and a man of action. Few can match his remarkable career chapters of public official, historian, writer, and educator. He is now bringing all those experiences together to reflect as Shakespeare did on the nature of power—how it can be used for good, how it can corrupt, and how it can be fragile and transient. Seeing the Civil War, World War II, and the war in Ukraine through the Shakespearean lens provided by Cohen is both illuminating and educational, as is considering how Vladimir Putin’s utter lack of a moral center is not unlike Richard III. Readers who love literature and history will love this book.”General James Mattis, former United States secretary of defense

-

“A terrific book by a thoughtful, articulate, and exceptional teacher-practitioner. In government and out, Cohen has consistently been one of the shrewdest observers of the exercise of power, and now we know one reason why: his mastery of Shakespeare. The Hollow Crown is a great read that is as instructive as it is enjoyable.”David H. Petraeus, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency

-

“The acquisition, holding, and loss of power in every realm of life are subjects of enduring fascination, most especially to William Shakespeare. Cohen, no stranger to power himself, in The Hollow Crown has written a remarkable book delving into Shakespeare’s unique insights into the psyche and arts—dark and otherwise—of those who wield power. Cohen brings his own perspective to the lessons Shakespeare offers about leadership for our own age, above all, ‘the preeminent importance of character in all of its complexity.’ The Hollow Crown is a must-read for self-understanding by all who seek or hold power and for those who seek insight about them from the greatest observer of human nature in the English language.”Robert M. Gates, former United States secretary of defense

-

“Cohen has come up with a genius idea for an entirely original book on leadership. Drawing on his encyclopaedic knowledge of Shakespeare—mainly the history plays, but also some of the tragedies—he weaves in his profound knowledge of modern politics to produce a subtle, scholarly, and highly convincing account of what it means to be a leader. This book represents an intriguing, insightful, witty, and often unsettling tour de force.”Andrew Roberts, author of Churchill

-

“After a career spent walking the corridors of power, Cohen now turns to Shakespeare to explain what he saw and experienced. Witty and erudite, this book relates Shakespeare’s heroes, rogues, and tyrants to the modern world, producing lessons all of us can use.”Anne Applebaum, author of Red Famine

-

“To Cohen’s many laurels earned as a public servant and scholar, add another: his deep reading of the West’s deepest student of humanity has yielded perennially pertinent lessons about the challenges of governance.”George F. Will

-

“The Hollow Crown is a book that’s not just about Shakespeare—it’s a guide to understanding power, and it should be required reading for anyone seeking to understand the mysteries of Washington in these troubled times. The book draws skillfully on Cohen’s years of experience observing the foibles of leaders up close to add modern perspective to the iconic kings and tyrants, generals and demagogues, who populate Shakespeare’s plays. It is insightful, fast-moving, and strikingly relevant to the present day.”Susan Glasser, coauthor of The Divider

-

“Thank goodness there still people in America who think and write with the subtlety of Cohen. His brilliant meditation on power and statecraft, The Hollow Crown, is a double helix; he takes us deep into Shakespeare’s plays and emerges with vivid portraits of our modern political figures. In Cohen’s reading, Shakespeare becomes a kind of Elizabethan Machiavelli—a man who observes power and politics with such a nuanced and unsentimental eye that his work is timeless. Cohen finds some astonishing Shakespearean moments on the American political stage—from Washington and Lincoln to Nixon and Obama—presidents whose ambitions and flaws match the characters Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies. People worry that reading and critical analysis are dying arts in America. Here’s powerful evidence it isn’t so.”David Ignatius, columnist, Washington Post

-

"Eliot Cohen's fine and beautifully written book should and hopefully will become mandatory teading for all students of political science and IR: and prior deep knowledge of the Bard is not a prerequisite. Indeed, it's also a good entry point to Shakespeare as well."Francois Heisbourg, Senior Advisor for Europe, International Institute for Strategic Studies