Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

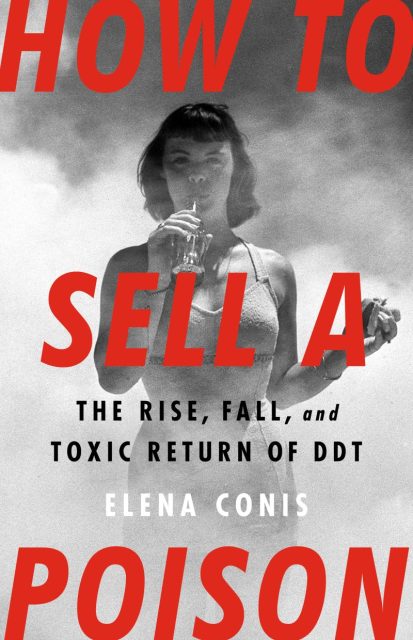

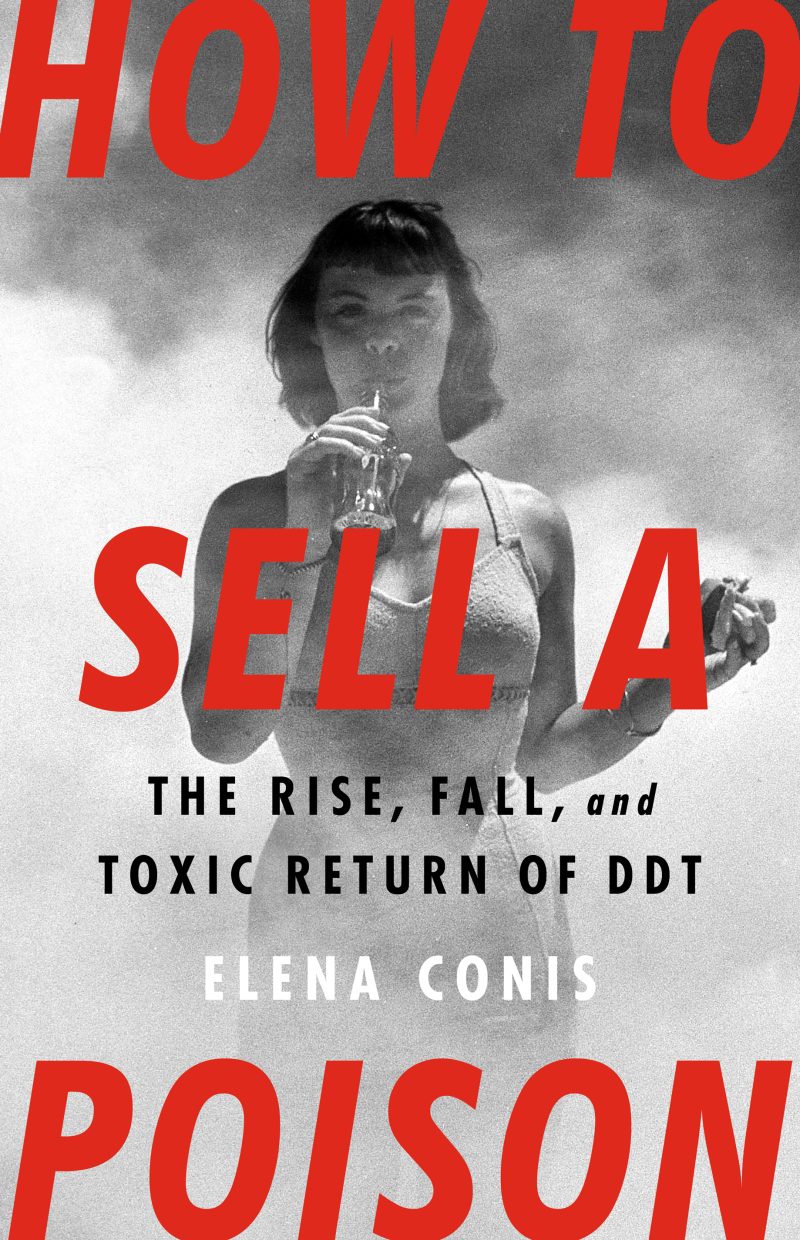

How to Sell a Poison

The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT

Contributors

By Elena Conis

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 12, 2022

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645036746

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 12, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The story of an infamous poison that left toxic bodies and decimated wildlife in its wake is also a cautionary tale about how corporations stoke the flames of science denialism for profit.

The chemical compound DDT first earned fame during World War II by wiping out insects that caused disease and boosting Allied forces to victory. Americans granted it a hero’s homecoming, spraying it on everything from crops and livestock to cupboards and curtains. Then, in 1972, it was banned in the US. But decades after that, a cry arose to demand its return.

This is the sweeping narrative of generations of Americans who struggled to make sense of the notorious chemical’s risks and benefits. Historian Elena Conis follows DDT from postwar farms, factories, and suburban enclaves to the floors of Congress and tony social clubs, where industry barons met with Madison Avenue brain trusts to figure out how to sell the idea that a little poison in our food and bodies was nothing to worry about.

In an age of spreading misinformation on issues including pesticides, vaccines, and climate change, Conis shows that we need new ways of communicating about science—as a constantly evolving discipline, not an immutable collection of facts—before it’s too late.

-

“Monumental…One of Conis’s greatest achievements is to put a human face on this science of risk.”The New Republic

-

“How to Sell a Poison deepened my understanding of this chemical in unexpected ways… It’s a gripping examination of corporate influence over science — and how this tried-and-true playbook continues to manipulate public opinion today… Conis has a prescient way of framing the past so as to inform our future.”Los Angeles Times

-

“Conis writes with a journalist’s clarity and remove, and a historian’s exacting fidelity to primary sources. She conveys her findings through narrative (more than through historical argument), with scenes rich in dialogue and description.”Los Angeles Review of Books

-

“Rich in human narratives… How to Sell a Poison sounds a warning about how easily scientific understanding can be undermined by outside forces.”Civil Eats

-

“The phrase ‘trust the science’ should be replaced with ‘understand how the science gets made.’ This deeply researched, beautifully written, and well-argued explanation of how DDT was sold, misregulated, and resold should scare everyone from the ardent scientist to the fearful conspiracy theorist into rethinking.”Susan M. Reverby, author of Examining Tuskegee

-

“What Merchants of Doubt did for earlier campaigns of corporate disinformation, How to Sell a Poison does, superbly, for a toxin I thought we’d gotten rid of. Elena Conis’s fast-paced account is all the more important in an era when powerful forces are trying to discredit science.”Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopold's Ghost

-

“Elena Conis is a historian who writes nonfiction like a fiction writer. In elegant prose, she reveals the often forgotten and captivating history of how ordinary people discovered the dangers of DDT—and persisted in having it banned against all odds and despite false assurances of its safety from public health officials.”Sheldon Krimsky, author of GMOs Decoded

-

"Why do we still talk about DDT? In this provocative and richly detailed retelling of the DDT story, Elena Conis deftly explores why a pesticide banned since 1972 remains so politically divisive. For Conis, the answer lies in the intersection of science and politics, revealing a story rooted in the past, but framed by contemporary political and ecological debates. It is a fascinating story that will resonate with readers trying to make sense of the uncertainty of scientific knowledge in our highly politicized world.”David Kinkela, author of DDT and the American Century

-

"Science is often thought to be the antonym of politics. Yet the human side of innovation, along with fierce competition, can create the conditions for behavior that is anything but apolitical. How to Sell a Poison brilliantly retells the story of the rise, fall, and reemergence of DDT to highlight how context shapes what we think we know about science and health policy. Rigorously researched and delightfully written, this book sets a new standard for science journalism."Osagie Obasogie, author of Blinded by Sight

-

“In How to Sell a Poison, Elena Conis skillfully narrates the complex, toxic history of DDT, among the world’s most popular and dangerous chemical pesticides. Initially heralded, ultimately banned, still widely used, the vagaries of the production, sale, and regulation of DDT opens up the most fundamental questions of corporate greed, the role of government, and scientific practice. Anyone interested in the problem of scientific authority in our toxic world should read this important, essential book."Allan M. Brandt, author of The Cigarette Century

-

"Elena Conis has rendered a frightening and thoroughly researched account of the poisoning of our environment and ourselves. With great precision and keen analysis, she plainly lays out the case for how one of the twentieth century’s most large-scale toxic exposure events was the direct result of corporate greed and manufactured doubt of science. The story always has been urgent, but no more so than now.”Samuel Kelton Roberts, Jr., author of Infectious Fear

-

“A collection of shocking narratives…[Conis] captivatingly examines decades of conflicting reports from scientists and government agencies regarding the pesticide’s toxicity, lawsuits and governmental hearings related to DDT, the related formation of the Environmental Protection Agency, and recent efforts by private interests to revive production…An insightful, timely work about ‘the endless game of catch-up we play when we pollute first, regulate later.’”Kirkus Reviews

-

“Conis’s account is impressively researched, and her narrative carefully constructed. This is a worthy contribution to environmental history.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Conis delivers a compelling, copiously researched account of DDT in America that is both uplifting and utterly bleak…A vitally important contribution to the ongoing discussion over the use of pesticides.”Booklist

-

“A superb and well-researched account of a notorious chemical and the clash it has provoked between science and corporate doubters.”New York Journal of Books

-

“[A] complex, disturbing study.”Nature