By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

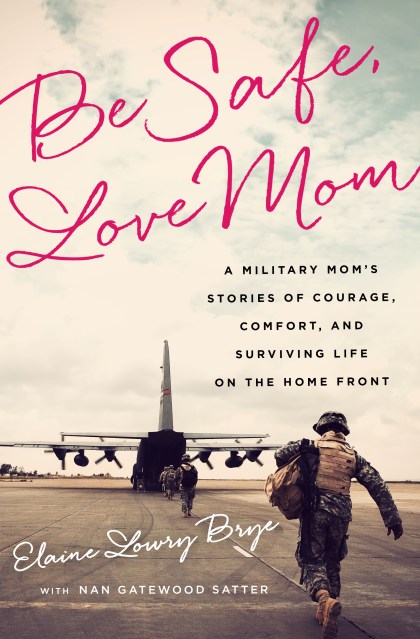

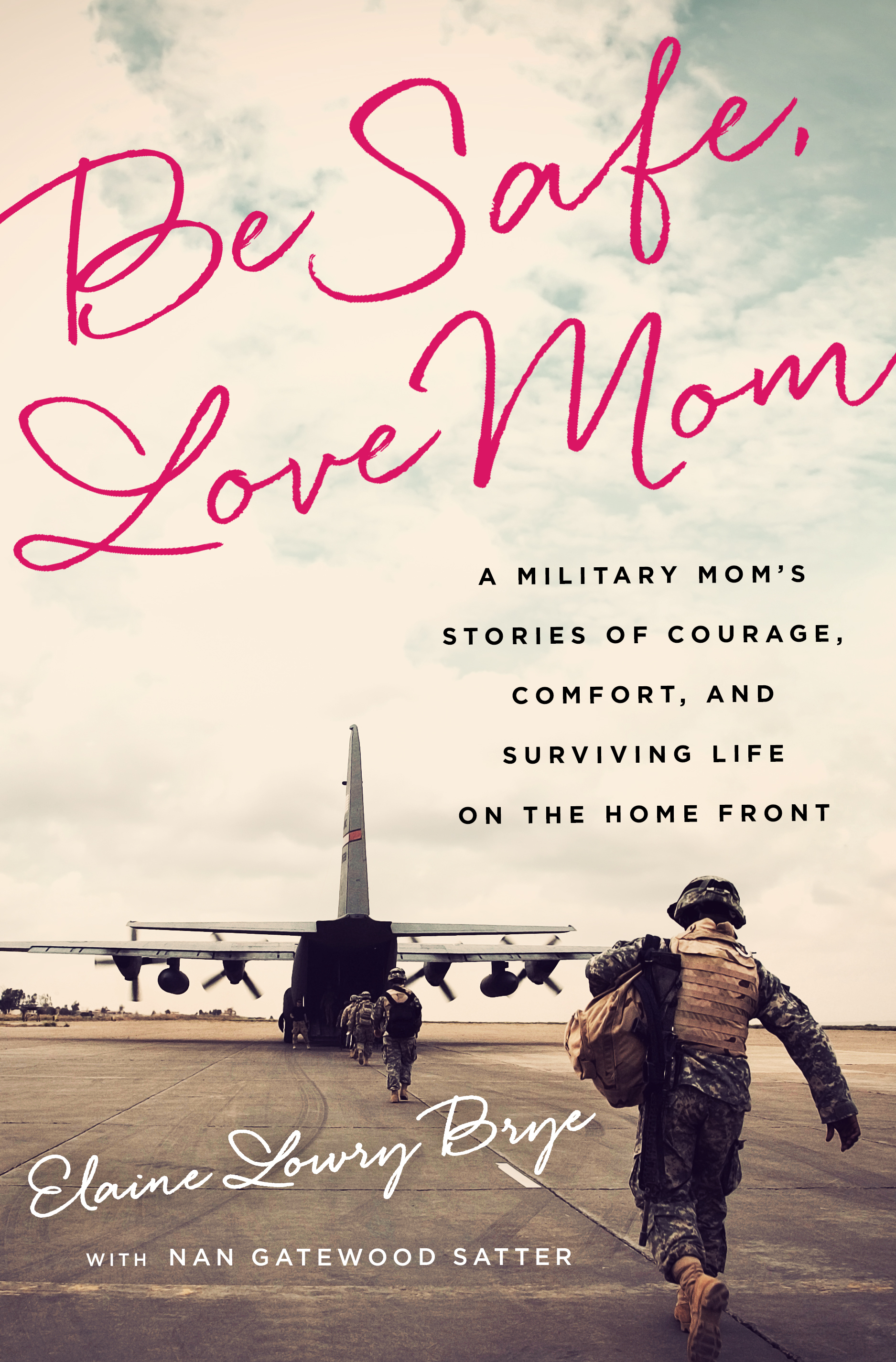

Be Safe, Love Mom

A Military Mom's Stories of Courage, Comfort, and Surviving Life on the Home Front

Contributors

With Nan Gatewood Satter

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 31, 2015

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395229

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 31, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When you enlist in the United States military, you don't just sign up for duty; you also commit your loved ones to lives of service all their own.

No one knows this better than Elaine Brye, an "Army brat" turned military wife and the mother of four officers-one each in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps. Be Safe, Love Mom braids together Elaine's own personal experiences with those of fellow parents she's met along the way. She offers gentle guidance and hard-earned wisdom on topics ranging from that first anxious goodbye to surrendering all control of your child, from finding comfort in the support of the military community and the healing power of faith to coping with the enormous sacrifices life as a military mother requires.

With hard-to-come-by information and encouragement that is like advice from a wise and trusted friend, Be Safe, Love Mom is an essential handbook to membership in a strong and special sisterhood.

-

“An invaluable guide for parents and family of U.S. military service members, Be Safe, Love Mom offers both comfort and invaluable, hard-won advice from a woman who knows all about the emotional rigors of military life. Elaine Lowry Brye is herself an ‘Army brat’ and Air Force wife, one who went on to become the mother of four military officers (one each in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines). Brye’s is a book meant to provide sympathy and practical support to families like hers by getting real about the overwhelming emotions involved in watching a loved one enter the armed forces, and serves as a reminder to all of the sacrifices made not just by our fighting men and women but by their families, as well.”Archetypes.com

-

“A simply written, very honest book about how parenting a child at war feels. Through author Brye’s experiences and those of others who share their stories with her, one gains an understanding of the demands made on families, demands and sacrifices that don't make the national news until a flag-draped coffin is involved. Poignant sometimes to point of inducing tears, Be Safe, Love Mom is not easy reading. It may not even be possible to read at one setting, but it is one of those books that ought to be required reading for every citizen.”New York Journal of Books

-

“The military brat, spouse, and veteran whose four children are officers has only heartfelt concern for ‘we mothers’ and, presumably, fathers. Parents might appreciate reading her comforting momilies (yes, ‘momilies’) while ‘on this roller-coaster ride for which your child has volunteered you.’”Military Times

-

“This is a story for all families, as the nurturing love of a mom watches her children grow, while also learning when to let go. For a generation tempered by the horrors of September 11, two wars, and terrorism, Be Safe, Love Mom reminds us that sacrifice isn’t just on the battlefield, but in our homes. Her poignant stories of courage will move you, the honor of these brave men and women in uniform will inspire you, and the book will reaffirm your faith in our country.”Steve Scully, former senior executive producer and political editor, C-SPAN

-

“Elaine Brye’s book belongs in every military home... Every mother of a military child who reads this will nod her head knowingly, grateful that someone was able to understand what she faces and share it on her behalf.”Lisa Hallett, cofounder and president, wear blue: run to remember

-

“The stress of combat deployment on a soldier or Marine is far better understood than that on his family. Soldiers aren’t in harm’s way 24/7, but their loved ones don’t know that. For them there is not a minute in the day when they’re not worried. Be Safe, Love Mom helps us understand the sacrifices and stresses carried by the families, especially the kids.”Terry English, former president, Special Forces Trust

-

“Be Safe, Love Mom is a must-have manual for families of active-duty military members that reads like a letter from a dear friend.”L. Anne Babb, PhD, traumatic stress expert and recipient of the Jefferson Award for Public Service

-

“An invaluable handbook… For nonmilitary families, her work is a powerful reminder of the sacrifices made by those who serve and by their loved ones. For military families, Brye’s book will comfort and inform.”Publishers Weekly

-

“A compassionate, insightful guide for military parents and the rest of us who are in their debt.”Kirkus Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use