Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

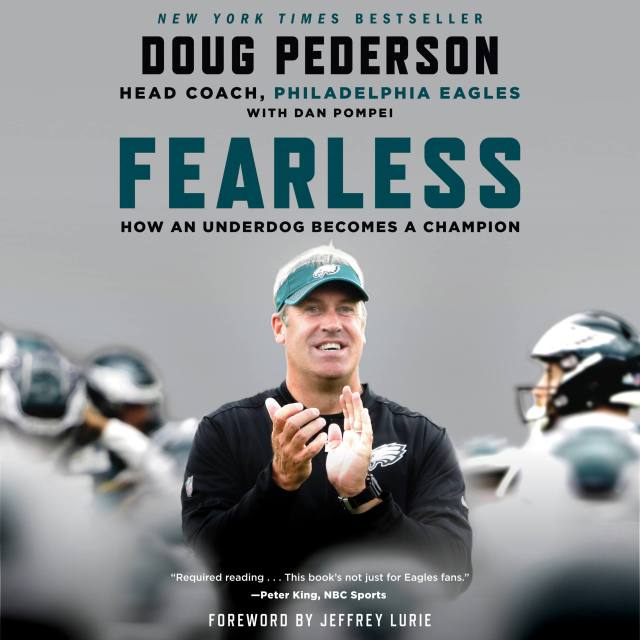

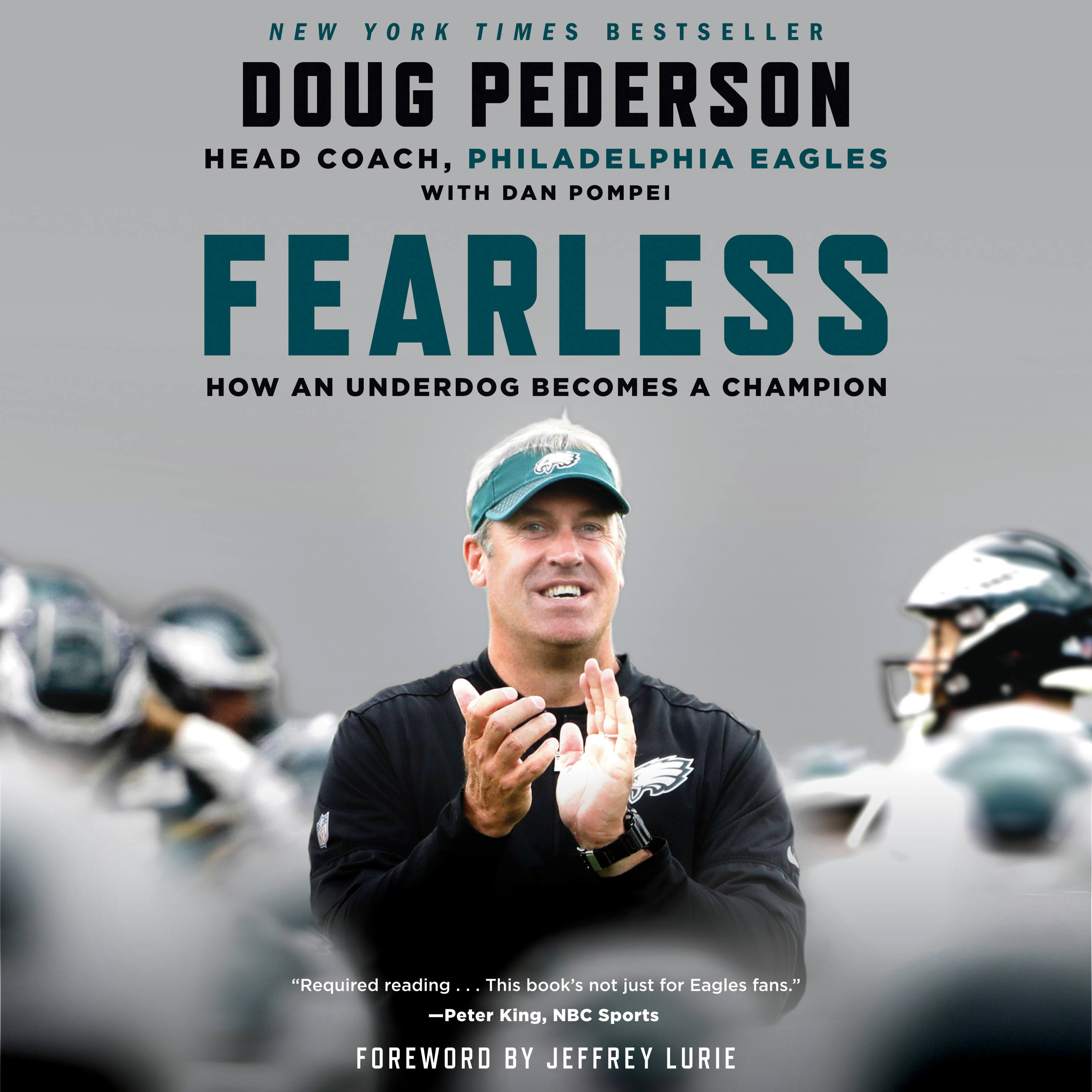

Fearless

How an Underdog Becomes a Champion

Contributors

With Dan Pompei

Read by Robert Petkoff

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 21, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549173646

Price

$24.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 21, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Doug Pederson is the very definition of an underdog. He was an undrafted rookie free agent who would go on to play fourteen years in the NFL as a backup quarterback. He was cut five times, yet kept getting back up and into the fray. He would win one Super Bowl, with the Green Bay Packers. When he retired, he decided to coach, but not at the pro level. Instead, he was head coach of Calvary Baptist Academy in Shreveport, Louisiana. After a successful four-year stint there, he returned to the NFL as an assistant coach under Andy Reid with the Eagles and the Kansas City Chiefs, where he was instrumental in the development of quarterback Alex Smith and his string of 3,000-plus-yard seasons of passing.

When he was offered the job as head coach of the Eagles, he jumped at it, though few thought he would succeed. In the first season, a year of rebuilding, they finished 7-9. Some doubted his abilities, and before the 2017 season, one “expert” called Pederson the least qualified coach in thirty years. Plagued by the sidelining of seasoned players and devastated by quarterback Carson Wentz’s season-ending knee injury, the Eagles managed a 13-3 record and home-field advantage in the playoffs. Yet they were still the underdogs in every single game, including the Super Bowl, against the New England Patriots, one of the greatest dynasties in the history of the NFL. It wasn’t until they stunned the Patriots that people finally believed in Pederson and his team.

In Fearless, Pederson reveals the principles that guided him through the ups and downs and tough times of his career, and what it took to become a champion. Through it all, Pederson sustained himself with his faith and the support of his family. He shares the defining stories of his life and career, growing up with his disciplinarian Air Force dad and his tender-hearted mom, developing friendships with Dan Marino and Brett Favre, and learning from mentors, such as Don Shula, Mike Holmgren, and Andy Reid, who helped mold him into the man and coach he is today.

Fearless captures Pederson’s coaching and leadership philosophies and reveals the brilliant mind and indomitable spirit of a man who has entered the pantheon of great coaches.

-

"Required reading for modern coaches in any sport...Pederson [is] the perfect example of intelligent risk-taking....The book's not just for Eagles fans. Coaches, and fans, in all sports will learn from it."Peter King, NBCSports.com

-

The story of Eagles head coach Doug Pederson [is] more than a little interesting....An engaging memoir."Christian Science Monitor

-

"What Doug Pederson did during the Eagles' Super Bowl season was one of the best coaching jobs I have ever seen in the NFL, and really in all sports."Jeffrey Lurie, from the foreword

-

"Philadelphia's head coach may have done something even more impressive than winning a Super Bowl: He wrote an interesting and entertaining football book...Pederson is one of the handful of coaches on the cutting edge of the sport...A love letter to aggressive play calling [Fearless] give[s] good insight into the modern football world."TheRinger.com

-

"Pederson emerges as a different kind of coach. Less autocratic than most NFL head men, he's aBooklist

bit more attuned to the culture and the atmosphere surrounding the team....Fine reading for any NFL fan." -

"Reveals much about the leader, the champion, and, best of all, the man. Pederson discusses the principles that guided him through the ups and downs of his career and what it took to lead his team to a Super Bowl win."SJ Magazine

-

"On the arm of his backup quarterback, Doug Pederson and the Philadelphia Eagles achieved a miracle....Pederson shares how he along with his team accomplished one of the most memorable Super Bowl victories in NFL history."CBN's 700 Club