By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

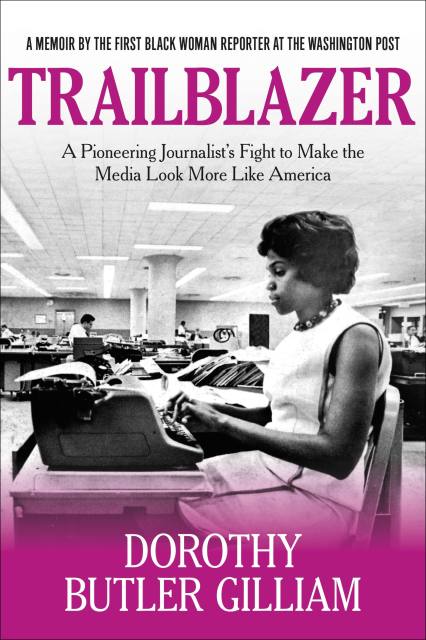

Trailblazer

A Pioneering Journalist's Fight to Make the Media Look More Like America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2019

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546083450

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Most civil rights victories are achieved behind the scenes, and this riveting, beautifully written memoir by a “black first” looks back with searing insight on the decades of struggle, friendship, courage, humor and savvy that secured what seems commonplace today-people of color working in mainstream media.

Told with a pioneering newspaper writer’s charm and skill, Gilliam’s full, fascinating life weaves her personal and professional experiences and media history into an engrossing tapestry. When we read about the death of her father and other formative events of her life, we glimpse the crippling impact of the segregated South before the civil rights movement when slavery’s legacy still felt astonishingly close. We root for her as a wife, mother, and ambitious professional as she seizes once-in-a-lifetime opportunities never meant for a “dark-skinned woman” and builds a distinguished career. We gain a comprehensive view of how the media, especially newspapers, affected the movement for equal rights in this country. And in this humble, moving memoir, we see how an innovative and respected journalist and working mother helped provide opportunities for others.

With the distinct voice of one who has worked for and witnessed immense progress and overcome heart-wrenching setbacks, this book covers a wide swath of media history — from the era of game-changing Negro newspapers like the Chicago Defender to the civil rights movement, feminism, and our current imperfect diversity. This timely memoir, which reflects the tradition of boot-strapping African American storytelling from the South, is a smart, contemporary consideration of the media.

-

Praise for TRAILBLAZERKirkus

"An important document of the struggles (and triumphs) faced by African-American journalists from the 1960s until today." -

"Dorothy Gilliam is that most rare of revolutionaries, one who not only climbs the barricades, but lets down a ladder to help others up, too. In her more than six decades at the centers of journalism in New York and Washington, she has often been the first African American woman and the best of everything. Her memoir shows us that a few can be both, but no one should have to. We will have no democracy until each of us can be our unique individual selves."Gloria Steinem, feminist activist, writer, editor, lecturer who also helped create New York and Ms. Magazine

-

"Dorothy Gilliam lived a fascinating life and shares it with you in Trailblazer. She started out afraid to tell her editors that D.C. cabs wouldn't stop for her-a problem for a reporter who needed to get to stories on time. She wound up a member of a group of minority columnists who regularly interviewed presidents."Her book is a tribute to her generous spirit. No one made greater efforts to share her success with others, to teach school-age journalists, to open the ranks of newspaper management to minorities."So many people in journalism are grateful that they met Dorothy. Here's your chance."Don Graham, former publisher of The Washington Post

-

"Dorothy Gilliam is a great reporter, a pioneer for all women in the news business, and African-American women particularly. Her story is about a time in American journalism where courage and brilliance were called for in the white-male bastions that were American newsrooms. It's a story that has been waiting a long time to be told."Carl Bernstein, Pulitzer prize-winning reporter of Watergate Fame

-

"Dorothy Butler Gilliam's inspirational life story is the journey of a daughter of the South who became a pioneering black woman journalist, an influential voice in the pages of The Washington Post, a national leader of the movement to foster diversity in the news media, and a dedicated mentor of countless aspiring young journalists. It is also the story of her role in a remarkable era of growth and influence of a leading American newspaper now evolving in the digital age. And it is a welcome gift for colleagues and readers who have benefitted from her work and presence in our lives."Leonard Downie Jr., former executive editor of The Washington Post, Weil Family Professor, Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communications

-

"Dorothy Gilliam has contributed a rare and important history of the journey of a Black reporter, who is also a woman, focusing on the Washington Post, but which has implications for the entire industry, writ large. Such a book would have always been a great contribution to the canon, but it is even more relevant today as the industry, as well as the society grapples with diversity and the way forward. Dorothy Gilliam provides answers that give us a road map to successfully navigate that way forward.Charlayne Hunter-Gault, internationally-known journalist and former foreign correspondent for National Public Radio and the Public Broadcasting Service

-

"Dorothy Gilliam is a national treasure. Her groundbreaking career in journalism is a monument to triumph, inspiration, grace. She is admired by journalists of color everywhere-not only because of her pioneering body of work, but because she cared about us so much."Kevin Merida, editor in chief of ESPN's The Undefeated and former managing editor of The Washington Post

-

"For those in the forefront, those "Firsts" of Black America, life was seldom a crystal stair to a glorious summit. Dorothy Butler Gilliam's memoir of her life and times chronicles such an ever- upward climb, step by step.Hers is the story of a woman ahead of her time, yet deeply involved in the critical issues of that time, and deeply concerned about younger ones in time yet to come.She succeeded at one of the premier American newspapers, charting a path of determination, commitment and inspiration for others to discover and appreciate, and to follow as well."Milton Coleman, retired senior editor, The Washington Post

-

"Powerful voice, inextinguishable brilliance, quiet strength, elegant beauty, visionary leader, honored journalist: Dorothy Gilliam. First African-American female journalist at the Washington Post, Dorothy Gilliam is a trailblazer who still is having an impact on journalists and journalism. It's my honor to know Dorothy, serve on the board of the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education and be one of her many fans who credit Dorothy with being an early career role model."Paula Madison, first executive vice president of diversity at NBC Universal, author

-

"Dorothy Gilliam didn't just shatter racial and gender barriers at The Washington Post, she shattered the journalistic view that white 'objectivity' was the only way of seeing the world. Gilliam pioneered a way of writing about African Americans that was accurate, balanced and compassionate-principles that had only applied to the coverage of whites before she arrived. The courage and intellectual rigor that it took for her to become the first African American woman journalist at the Post makes her a revered elder among black journalists today. Transforming the practice of journalism and paving the way for others makes her a legend for all time."Courtland Milloy, fellow columnist at The Washington Post

-

"As a documentary filmmaker whose work focuses primarily on African American history, politics, and culture, I find Dorothy Gilliam's trailblazing career and body of work to be invaluable. I'm thrilled by the thought of having her memoirs as a reference, offering insight and wisdom to my understanding of those who paved the way for so many, including me, in the field of journalism. I look forward to them and those aspects that she will share for my upcoming MSNBC documentary In the Line of Fire: The Media and the Movement (WT). Due to air in April 2018, Ms. Gilliam will be a primary resource and as such, I intend for her forthcoming memoir to be recognized by name in the program."Phil Bertelsen, Producer/Director, arkmedia

-

"Dorothy Gilliam offers a needed perspective as the news industry contemplates where it stands 50 years after the Kerner Commission declared that 'the journalistic profession has been shockingly backward in seeking out, hiring, training, and promoting Negroes.' Her experience grappling with this most intractable issue is without peer. Her observations deserve as many platforms as can accommodate them."Richard Prince, columnist, "Richard Prince's Journal-isms," reporting on diversity issues in the news media

-

"I would like to take this opportunity to support publication of Dorothy Gilliam's memoir, First Black Woman at The Washington Post, Dorothy Butler Gilliam's Life and Role in the Struggle to Diversify the Media. I began researching Ms. Gilliam's background several years ago when researching a book (scheduled for publication in September 2017) about the reporters who were on the Ole Miss campus during the 1962 integration riot. Ms. Gilliam is one of 12 reporters featured in the book because of her experiences as a woman in journalism, and as an African-American reporter during the civil rights era. Her background speaks of a woman who faced challenges, and did not let them stop her, and, as a woman who used her profile to lecture and encourage a generation of journalists to succeed no matter the barriers set into place. She has many stories to tell, the writing skills to do the job and the eye for detail that should result in a stunning memoir."Dr. Kathleen Wickham, Professor/Journalism, School of Journalism & New Media, The University of Mississippi

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use