By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

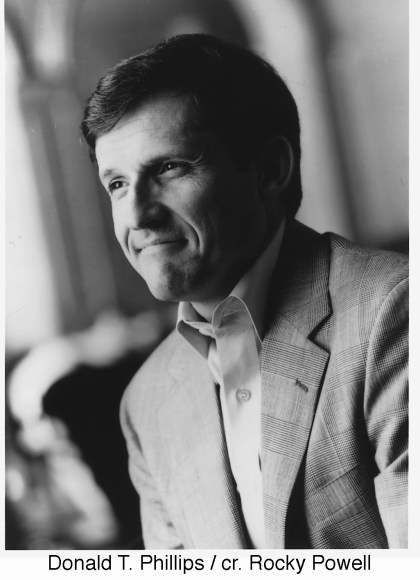

Martin Luther King, Jr., on Leadership

Inspiration and Wisdom for Challenging Times

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 1, 2001

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780759521094

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 1, 2001. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Martin Luther King Jr. is known for famous speeches such as I Have a Dream, and his ability to inspire the people of the United States to demand equality, regardless of the color of their skin. His ability to lead has cemented himself as one of America's greatest civil rights advocates.

And in today's world, his wisdom and teachings are needed more than ever. Martin Luther King Jr., On Leadership chronicles the actions of Martin Luther King Jr.'s life and identifies the key leadership skills he displayed such as:

Practice what you preach

Take direct action without waiting for other agencies to act

Give credit where credit is due

Laws only declare rights, they do not deliver them

And much more . . .

This book is part history and part guide to becoming a great leader, inspired by Martin Luther King Jr., an advocate to peaceful change while never wavering in making the opposition listen and give in.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use