Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

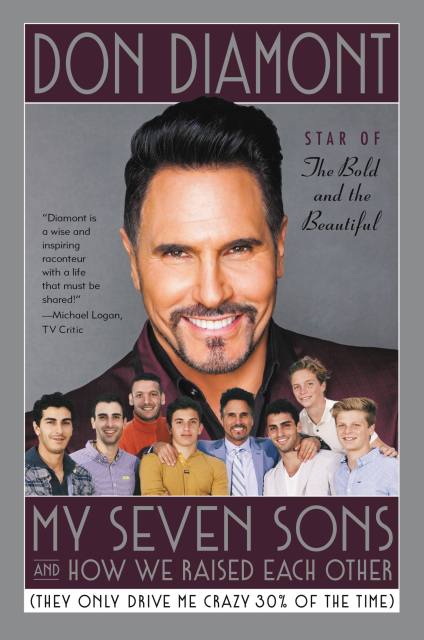

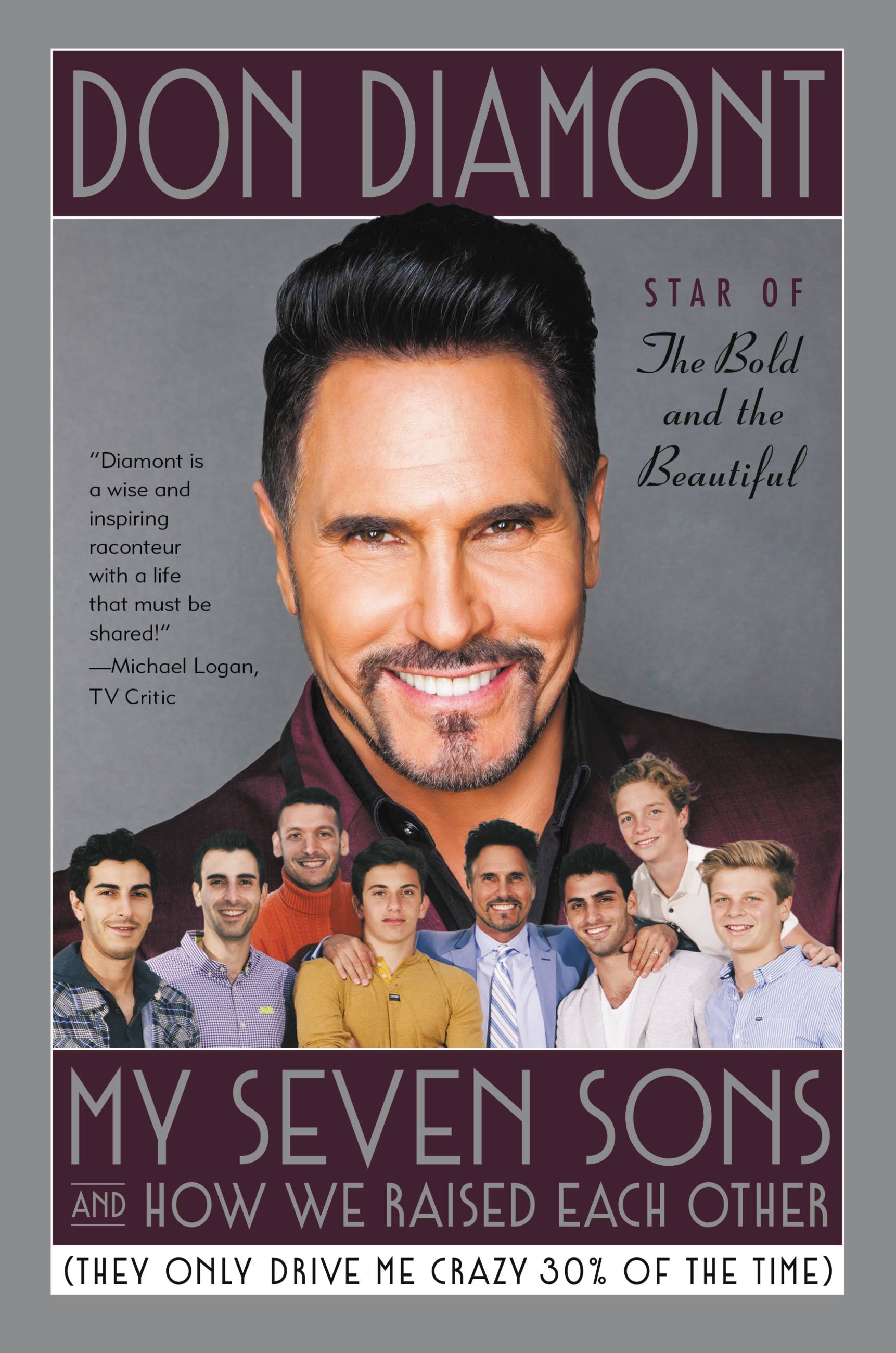

My Seven Sons and How We Raised Each Other

(They Only Drive Me Crazy 30% of the Time)

Contributors

By Don Diamont

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.00 $34.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 29, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Called a “daytime deity” by Soap Opera Digest, Don Diamont is best known as the dashing publishing titan with steel abs, “Dollar Bill Spencer,” on the most-watched daytime drama in the world, The Bold and the Beautiful.

But all of that takes second place to his most important role to date: father to seven boys.

By turns hilarious and poignant, My Seven Sons and How We Raised Each Other is a family memoir for our time. Don writes with openness and courage about the ways his family came together: by marriage, divorce, the death of his sister, and marriage again. Today’s blended families might look different from the households of even a few decades ago, but the first dates, first cars, busting curfew, talking back, grounding, broken hearts, laughs, tears, and the love are the same.

From his childhood growing up in LA, to his Zoolander phase as a model in both Paris and Los Angeles, to the iconic place he now occupies in daytime television, Don also gives us a glimpse into a life that at times could have been scripted for a soap opera. And, with brutal honesty, he tells of the personal devastation he suffered after the deaths of his father, brother, and sister.

My Seven Sons is required reading for everyone who is a parent, and all those who have one.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 29, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455568901

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use