Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

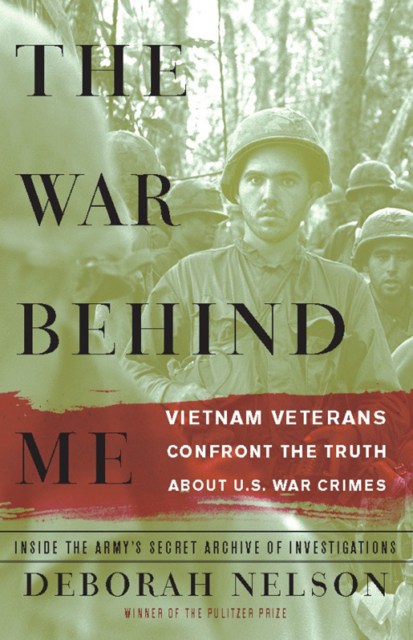

The War Behind Me

Vietnam Veterans Confront the Truth about U.S. War Crimes

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 28, 2008

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786726783

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 28, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The files contain reports of more than 300 confirmed atrocities, and 500 other cases the Army either couldn’t’t prove or didn’t’t investigate. The archive has letters of complaint to generals and congressmen, as well as reports of Army interviews with hundreds of men who served. Far from being limited to a few bad actors or rogue units, atrocities occurred in every Army division that saw combat in Vietnam. Torture of detainees was routine; so was the random killing of farmers in fields and women and children in villages. Punishment for these acts was either nonexistent or absurdly light. In most cases, no one was prosecuted at all.

In The War Behind Me Deborah Nelson goes beyond the documents and talks with many of those who were involved, both accusers and accused, to uncover their stories and learn how they deal with one of the most awful secrets of the Vietnam War.