Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

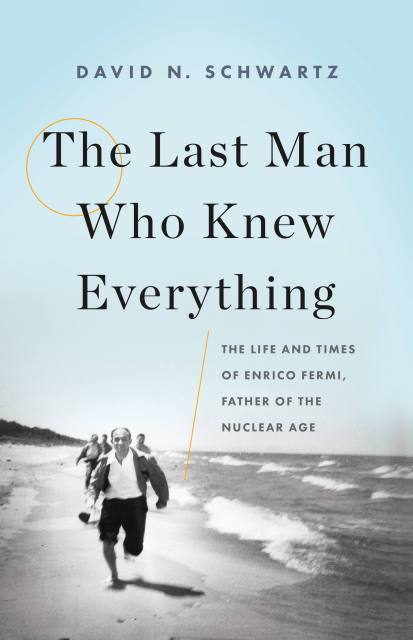

The Last Man Who Knew Everything

The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 5, 2017

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093120

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 5, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1942, a team at the University of Chicago achieved what no one had before: a nuclear chain reaction. At the forefront of this breakthrough stood Enrico Fermi. Straddling the ages of classical physics and quantum mechanics, equally at ease with theory and experiment, Fermi truly was the last man who knew everything — at least about physics. But he was also a complex figure who was a part of both the Italian Fascist Party and the Manhattan Project, and a less-than-ideal father and husband who nevertheless remained one of history’s greatest mentors. Based on new archival material and exclusive interviews, The Last Man Who Knew Everything lays bare the enigmatic life of a colossus of twentieth century physics.