By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

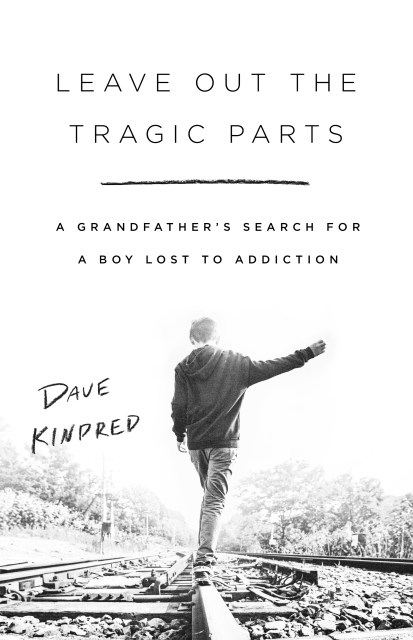

Leave Out the Tragic Parts

A Grandfather's Search for a Boy Lost to Addiction

Contributors

By Dave Kindred

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 2, 2021

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541757066

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 2, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Jared Kindred left his home and family at the age of eighteen, choosing to wander across America on freight train cars and live on the street. Addicted to alcohol most of his short life, and withholding the truth from many who loved him, he never found a way to survive.

Through this ordeal, Dave Kindred’s love for his grandson has never wavered.

Leave Out the Tragic Parts is not merely a reflection on love and addiction and loss. It is a hard-won work of reportage, meticulously reconstructing the life Jared chose for himself–a life that rejected the comforts of civilization in favor of a chance to roam free.

Kindred asks painful but important questions about the lies we tell to get along, and what binds families together or allows them to fracture. Jared’s story ended in tragedy, but the act of telling it is an act of healing and redemption. This is an important book on how to love your family, from a great writer who has lived its lessons.

-

"The title of Dave Kindred's astonishing book is precisely what he did not do. A world-class reporter used every ounce of his journalistic skills to investigate a story-the life and death of a beloved grandchild-that most of us would find daunting. But Kindred tells the story truly and with love."David Maraniss, author of A Good American Family: The Red Scare and My Father

-

"Dave Kindred's Leave Out the Tragic Parts is a searing, terrifying, and brilliantly written book that, when I began reading one night, I couldn't put down. As a tireless researcher devoted to finding and writing the unflinching truth about his beloved grandson, Kindred brings us into a fascinating, foreign world. In his remarkable journey, he explores and communicates the bafflement, desperation, and pain experienced by anyone who loves a person with addiction, and he reminds us that reading others' stories can lead to understanding, compassion, and healing. Leave Out the Tragic Parts is a godsend for every grandparent, parent, friend, spouse, and child who loves a person with addiction. It is testament to the power of love. I believe that the greatest art can come from the greatest pain and love, and this book is pure art."David Sheff, New York Times-bestselling author of Beautiful Boy

-

"Keening was the sound that confronted me on the other end of the line when Dave Kindred called to say his grandson Jared had been found dead of an overdose in a flop house in Philadelphia. The resounding howl of grief, anger, and bewilderment, would not abate until Kindred turned his consummate talents and unflinching gaze on Jared's all-too-brief life and unseemly death. Maybe, just maybe, if he could tell how the beautiful blond boy in a white tuxedo became a 'traveling kid' named Goblin-a wraithlike mess of tats and vodka-who hopped trains for a living, Jared's life would have some meaning and his grandpa would find some peace. Leave Out the Tragic Parts is a rageful lullaby of love and regret and a wonder to behold."Jane Leavy, New York Times-bestselling author of The Big Fella

-

“Leave Out the Tragic Parts is an emotional and psychological voyage into the psyche of a grief-stricken grandfather…. it must have required a great amount of courage and intestinal fortitude on the part of the writer...a home run.”The New York Journal of Books

-

“Leave Out the Tragic Parts serves as both an insightful look into the transient world of freewheeling American drifters while also being a vulnerable and open exploration of what it means to be a family watching a loved one struggling with addiction. Kindred’s frequent thoughts of ‘what if?’ will resonate with many.”Library Journal

-

“Powerful and deeply affecting.”Booklist, starred review

-

“A love letter. . . Kindred writes with an impressive combination of journalistic detachment and grandfatherly love . . .He approaches a difficult story with love and curiosity rather than sentimentality.”Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use