Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

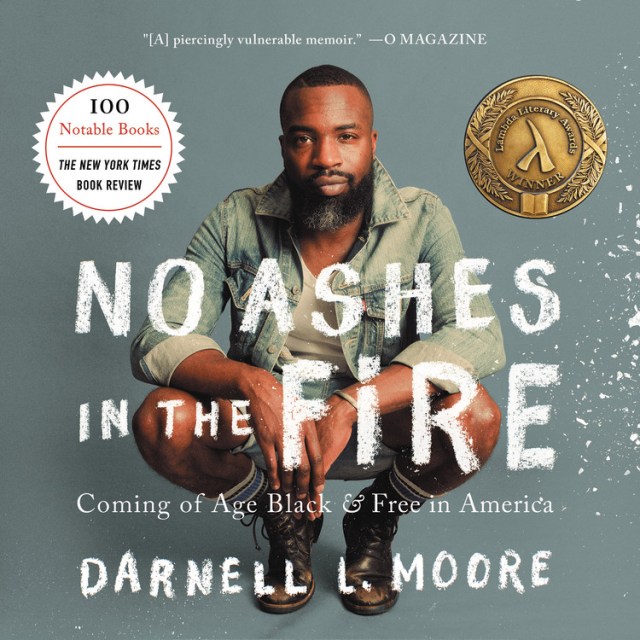

No Ashes in the Fire

Coming of Age Black and Free in America

Contributors

Read by Darnell L Moore

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 29, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Darnell Moore was fourteen, three boys from his neighborhood tried to set him on fire. They cornered him while he was walking home from school, harassed him because they thought he was gay, and poured a jug of gasoline on him. He escaped, but just barely. It wasn’t the last time he would face death.

Three decades later, Moore is an award-winning writer, a leading Black Lives Matter activist, and an advocate for justice and liberation. In No Ashes in the Fire, he shares the journey taken by that scared, bullied teenager who not only survived, but found his calling. Moore’s transcendence over the myriad forces of repression that faced him is a testament to the grace and care of the people who loved him, and to his hometown, Camden, NJ, scarred and ignored but brimming with life. Moore reminds us that liberation is possible if we commit ourselves to fighting for it, and if we dream and create futures where those who survive on society’s edges can thrive.

No Ashes in the Fire is a story of beauty and hope-and an honest reckoning with family, with place, and with what it means to be free.

Genre:

-

A New York Times Notable Book of the Year

-

"Stranded in the urban battleground of Camden, New Jersey... Moore struggles against a crush of bullying, bigotry, and self-loathing. He chronicles his odyssey in this piercingly vulnerable memoir, ultimately finding his way to LGBTQ activism and 'black joy' through faith and family."O Magazine

-

"A staggering work that calls into question the truths we assume about ourselves and those among us."Esquire

-

"In his frank debut memoir, journalist Moore recounts his experience growing up a queer black man in Camden, New Jersey in the 1980s. Loved by his vibrant but argumentative family and ostracized by many of his peers, Moore grapples with the complexities of his growing faith and burgeoning sexuality and his own self-loathing and self-acceptance in his journey to becoming an activist and outstanding voice in the Black Lives Matter movement."Harpers Bazaar

-

"Darnell Moore is one of the most influential black writers and thinkers of our time--a beautiful, intentionally complex feminist activist writing liberatory futures. I cannot wait for the world to read No Ashes in the Fire."Janet Mock, author of Redefining Realness and Surpassing Certainty

-

"No Ashes in the Fire is part memoir, part social commentary. Darnell honestly tells his story with an intensity and passion that offers readers a deep understanding of a gay black male coming of age who open-heartedly claims his identity, and who embraces redemptive suffering. Ultimately, he reaches out to everyone with an inclusive love."bell hooks

-

"No Ashes in the Fire illuminates the fragility of black life no matter how much love surrounds it. As he grapples with social tragedy and the insecurity of black masculinity, Moore displays magnificent self-reflection. He narrates his story in a looping, lyrical style that approaches complicated truths through metaphor.... For Moore, these efforts often take the form of an empathy that borders on the transcendent."Dawn Lundy Martin, Bookforum

-

"A brutally honest investigation and interrogation of the stories [Moore] was taught to tell himself in order to live... The prose is immaculately spare and razor-sharp, honed to pierce the armor of our own role in upholding and telling similar stories. He pairs trenchant systemic analysis with interpersonal forgiveness, marking the ways those that sought to cause him pain and even death were first, possibly irrevocably, damaged by the same stories they were told in order to live... It's the stories we tell ourselves that need to burn. And with No Ashes In The Fire, Moore strikes a match."Kevin Allred, INTO

-

"No Ashes in the Fire is everything that is quintessentially Darnell Moore: brilliant, courageous, transparent, and wholly original. Moore's masterful writing feels like equal parts soul music and gospel testimony. With this book, Moore positions himself as one of the leading public intellectuals of our generation. More importantly, he has written a text that will inspire, and maybe even save, many lives."Marc Lamont Hill, author of Nobody: Casualties of America's War onthe Vulnerable, From Ferguson to Flint and Beyond

-

"Darnell Moore is doing something we've never seen in American literature. He's not just texturing a life, a place, and a movement while all three are in flux; Darnell is memorializing and reckoning with a life, place, and movement that are targeted by the worst parts of our nation. He never loses sight of the importance of love, honesty, and organization on his journey. We need this book more than, or as much as we've needed any book this century."Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy

-

"Darnell Moore's No Ashes in the Fire is a searing, tender, and wise memoir. It is the captivating story of a man, a family, a community, and an age in the life of Black America in which old wounds and new possibilities meet at an earth-shaking crossroads. Moore is a reflective, contemplative, and instructive scribe. His are the words of an organizer, a social historian, and a fighter with a deep love for his people."Imani Perry, Hughes-Rogers Professor of AfricanAmerican Studies, Princeton University

-

"Radical black love is the major force for black freedom, as so powerfully embodied and enacted in Darnell Moore's courageous book. From Camden, New Jersey, as a youth, to Brooklyn, New York, as an adult, Moore takes us on his torturous yet triumphant journey through racist and homophobic America. Don't miss his inspiring story!"Dr. Cornel West

-

"Darnell L. Moore's powerful and inspiring memoir No Ashes in the Fire speaks to the bittersweet struggle to reconcile sexuality, spirituality, and masculinity during the vulnerable years of youth when violence in its various ruthless forms threatens to shatter both body and soul. Honest and revealing, Moore's sobering voice turns his unsettling truths into grace notes; his history of heartache into a poignant story of a hard-won triumph."Rigoberto González, author of Butterfly Boy: Memories of a ChicanoMariposa

-

"Darnell Moore reflects on what it meant to come of age during the bitter end of the 20th century. He maps the neoliberal political trends that collapsed cities like Camden, then blamed their demise on black children and their mothers. He unspools threads of intimate moments, locating his earliest memories of discovering desire for another boy. He recounts the violence that became the single story of his generation and deepens those annual murder rate statistics by raising the names and stories of the dead. He is in the radius as Hip Hop is born and considers its effect on posturing, on masculinity, on public joy. But mostly this is excavation work-digging past shame, conspiratorial family secrets. He is greatly served by the same curiosity that belonged to the smart, shy boy he was. As he navigates and collects memories, he unlocks closed doors that turned single rooms in a family home into silos of suffering. Healing and deep care is on the other side of this memory map, and it is a journey well spent."dream hampton

-

"In No Ashes in the Fire, Darnell Moore takes a single life-his own-to prove the principle of intersectionality: the so-called issues we'd like to push away from ourselves, those supposed other worlds we claim to only encounter on the news, are indeed the actual individual lives we lead. Moore shows us how he, and therefore each and every one of us, grapples with the myths surrounding sexuality, race, class, and loneliness. Or as Moore himself writes, "I lost myself because I had longed so badly to be found." No one goes unscathed, but on the other hand, no one goes untouched. This is a book of experience and survival."Jericho Brown, author of The NewTestament

-

"A rare debut... This is a holistic story, one that is as intersectional as real life."Colorlines

-

"Moore writes eloquently and powerfully about discovering his sexuality as a child, and how he came to understand both the impossibility and revolutionary potential of Black queer love in America."them

-

"A heart-wrenching memoir of triumphing over...racial violence."The Root

-

"Remarkable... No Ashes in the Fire is a love letter to black and queer people. It's an homage to those who have not only persevered but thrived when systematic oppression all but guaranteed their demise."ArtsATL

-

"[A] stirring and beautifully rendered memoir.... Part autobiographical, part social commentary, and entirely eye-opening, No Ashes in the Fire is a timely book about race, sexuality, class, and equality that everyone in America should be reading."Bustle

-

"In a word, Darnell L. Moore's compelling memoir No Ashes in the Fire is vulnerable... Moore takes readers through the glorious and traumatic experiences of his self-discovery."Philadelphia Inquirer

-

"Necessary... In the voice that's made him a standout writer, Moore gives readers much to chew and ruminate on."Bitch, The 30 Most Anticipated Nonfiction Books of 2018

-

"[A] bold and candid memoir... Moore's well-crafted book is a stunning tribute to affirmation, forgiveness, and healing--and serves as an invigorating emotional tonic."Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

-

"An open-hearted exploration of faith, fluid sexuality, and the myriad challenges of being a black American when advancement seems elusive as ever... Moore writes deftly in passages that purposefully meander to present a broad, socially engaged tableau of his experiences, though some of his observations can be repetitive. An engaging meditation on identity and creativity within challenging settings."Kirkus Reviews

-

"This coming-of-age memoir cum meditation is the introspective story of a man in search of self... A cultural and political history that examines and defies the stereotypes of black life in America.. [Darnell L. Moore's] story is an inspiration."Booklist

-

"Moore's commentary on racism, sexual orientation, and inequality makes this a must-read for our current social climate. Memoir and biography fans will eagerly consume this complex and varied account."Library Journal

-

"[Darnell L. Moore] is masterful at molding intensely personal experiences into universal sensations that touch every human at some point-and at doing so without clichés or self-help affirmations. We are terrified with the child Darnell who witnesses his father pelting his mother's back. We are shy and confused and loved with the Darnell whose father teaches him how to wash properly and to swim. Whether Darnell loves a man or a woman, we, too, desire and taste and quiver and regret and want again... Moore does the necessary work of affirming black humanity, and of unveiling Camden, his blackness, and his queerness as sources not of "nothing good," but of his invincibility."Women's Review of Books

-

"To be a good ally is to be a good listener. And everyone should listen to the story of Darnell L. Moore's life."Hello Giggles

-

"'You can't write!' a teacher once told Moore. This book says otherwise, and resoundingly."Shelf Awareness, Starred Review

-

"A lyrical conversation with the world."Sarah Schulman, Los Angeles Blade

-

"[Darnell L. Moore] is ready to tell the world his story of resilience and bravery."Popsugar

-

"Moore has given us a beautifully crafted memoir about the uniqueness of the Black queer experience. His reflections on institutionalized racism, classism, homophobia, and his personal journey in the midst of these barriers are vital because all too often are the least among us left out of the conversation. And the compassion he gives to those who have both loved and harmed him speak to his amazing spirit-a spirit that leaps off of the page."Michael Arceneaux, BuzzFeed

-

"With a style that evokes James Baldwin, activist Darnell Moore explores his life, religion, and society, attempting to reconcile the internalized agitation of black identity with the cultural fear of people of color that is widely on display in America. He is deliberate, both in his prose and his delivery. His soft, deep voice pulls listeners into this beautiful and engaging memoir about a black man coming to terms with his place in a racist society, his sexuality, his relationship with God, and his ability to impact that world. His voice conveys so much emotion without being emotional as he shares memories of kids almost burning him alive as a child, a shattering childhood Christmas, and his attempted suicide. The result is an audiobook that will strike a nerve with listeners."Audiofile

- On Sale

- May 29, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549168727

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use