By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

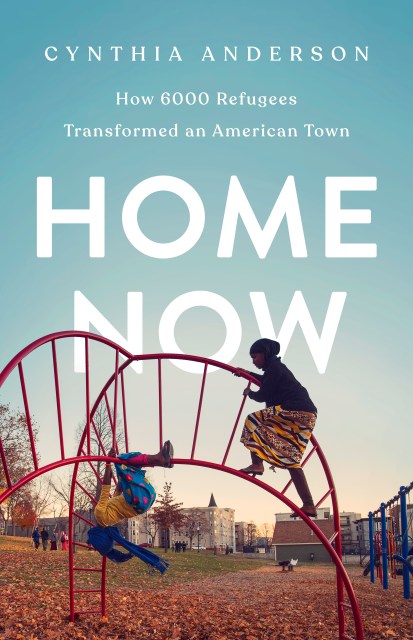

Home Now

How 6000 Refugees Transformed an American Town

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541767911

Price

$38.00Price

$48.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $38.00 $48.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A moving chronicle of who belongs in America.

Like so many American factory towns, Lewiston, Maine, thrived until its mill jobs disappeared and the young began leaving. But then the story unexpectedly veered: over the course of fifteen years, the city became home to thousands of African immigrants and, along the way, turned into one of the most Muslim towns in the US. Now about 6,000 of Lewiston’s 36,000 inhabitants are refugees and asylum seekers, many of them Somali. Cynthia Anderson tells the story of this fractious yet resilient city near where she grew up, offering the unfolding drama of a community’s reinvention–and humanizing some of the defining political issues in America today.

In Lewiston, progress is real but precarious. Anderson takes the reader deep into the lives of both immigrants and lifelong Mainers: a single Muslim mom, an anti-Islamist activist, a Congolese asylum seeker, a Somali community leader. Their lives unfold in these pages as anti-immigrant sentiment rises across the US and national realities collide with those in Lewiston. Home Now gives a poignant account of America’s evolving relationship with religion and race, and makes a sensitive yet powerful case for embracing change.

Like so many American factory towns, Lewiston, Maine, thrived until its mill jobs disappeared and the young began leaving. But then the story unexpectedly veered: over the course of fifteen years, the city became home to thousands of African immigrants and, along the way, turned into one of the most Muslim towns in the US. Now about 6,000 of Lewiston’s 36,000 inhabitants are refugees and asylum seekers, many of them Somali. Cynthia Anderson tells the story of this fractious yet resilient city near where she grew up, offering the unfolding drama of a community’s reinvention–and humanizing some of the defining political issues in America today.

In Lewiston, progress is real but precarious. Anderson takes the reader deep into the lives of both immigrants and lifelong Mainers: a single Muslim mom, an anti-Islamist activist, a Congolese asylum seeker, a Somali community leader. Their lives unfold in these pages as anti-immigrant sentiment rises across the US and national realities collide with those in Lewiston. Home Now gives a poignant account of America’s evolving relationship with religion and race, and makes a sensitive yet powerful case for embracing change.

-

"In this detailed, sensitive portrait of the city's revitalization by African immigrants... [Anderson] expertly captures the multilayered dynamics between Lewiston natives and African immigrants...The result is a vivid and finely tuned portrait of immigration in America."Publishers Weekly

-

"This compelling account relates how 6,000 African refugees came to settle in Lewiston, Maine... Anderson relies on several voices and story threads to convey the complexities of assimilation: long-time residents, concerned about strained resources; bewildered, often traumatized newcomers; passionate, steadfast activists; parents determined to provide better lives for their children; and government officials grappling with ingrained cultural traditions...Readers will find lots to think about."Booklist

-

"It's a book that feels both current and necessary, a microcosm of the immigration stories we see playing out daily on the national stage."Portland Press Herald

-

"[Anderson] chronicles the transformation of a formerly white town by an influx of Somali refugees, drawing on the perspectives of old and new residents...The result is a varied political picture."The New Yorker

-

"The arrival of thousands of African refugees in a fading Maine city is a situation ripe for a writer as gifted as Cynthia Anderson. Home Now is immediately relevant and universally resonant, as it illuminates the explosive politics of immigration and explores complex issues around our relationships to places and each other. The richly told stories of Fatuma, Jamilo, Nasafari, Abdikadir, Carrys, and the other remarkable people in these pages will deepen and expand the ways that readers see the world."Mitchell Zuckoff, New York Times-bestselling author of Fall and Rise: The Story of 9/11

-

"In this journalist's beautifully written, balanced, personal account, we learn how a former Maine mill town losing business 'like a mouth losing teeth' begins in 2001 to absorb 6,000 Somali, Congolese, and Sudanese refugees. . . . In discouraging times, such an honest and heartening read."Arlie Hochschild, bestselling author of Strangers In Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

-

"Home Now is a thrilling narration of the lives of the new Mainers settled in one of America's whitest towns--Lewiston, Maine. Cynthia Anderson humanizes the stories of the recent immigrants--many of them Somalis--who helped reawaken a sleepy town. As a recent Somali immigrant myself, I saw in this book a true, intimate, and timely account of what I live every day. This book should be read by everyone to learn about the stories, geography, tradition, strength, and resilience of their new neighbors."Abdi Nor Iftin, author of Call Me American

-

"A compassionate and insightful account of the human stories behind one of the most divisive issues in American politics."Farah Stockman, New York Times reporter and Pulitzer Prize winner

-

"Home Now is a breathtaking work of journalism and heart. Following several 'new Mainers' who arrive from war-ravaged African countries, Anderson brings her own deep Maine roots to bear as she illuminates their culture, assimilation, trauma, and homecoming. Her writing is graceful and clear-eyed and brimming with compassion both for the intrepid newcomers and the often-ambivalent citizens who receive them. I found it instructive, poignant, and riveting. We need this book right now."Monica Wood, author of The One-in-a-Million Boy and When We Were the Kennedys

-

"An essential book to remind us that racism and prejudice will never be more powerful than what binds us together in the great American mosaic--community, family, faith, and ultimately, hope. Cynthia Anderson provides an honest portrayal of being a Muslim immigrant in Trump's America."Ali S. Khan, dean of the School of Public Health, University of Nebraska

-

"Home Now folds us into a non-polemical but clear refutation of the villainization of immigrants. Families we come to know and respect have survived appalling hardship in Africa and settled in a Maine mill town that's been demoralized after factories closed or moved on. Nasafari Nahumure, Jamilo Maalim, and the many others on these pages--they stand in for about 6,000 new immigrants in all--help revitalize Lewiston's spirit and commerce. Cynthia Anderson's expert reporting welcomes us, in highly readable style, to the complex and constructive fate of the real America. Her careful rendering, and her insights, deepen our understanding of what's happening here and now."Mark Kramer, founding director of the Nieman Program on Narrative Journalism at Harvard University

-

"With great clarity and honesty, Cynthia Anderson blends intensely personal narratives with first-rate reporting to produce an indisputably necessary book for our times. Both an homage to those fearless immigrants who, through their industry and dedication, remake our country, and a wake-up call, Home Now gives us an America as it is now, today, not some bogus vision of what it never was. There's hope in this book, and struggle, and endurance-all beautifully and intimately captured. And you want to know what it is like at the Walmart at 9PM in late August in Lewiston? Anderson can tell you; she's been there."Peter Orner, author of Maggie Brown & Others and Am I Alone Here?

-

"With the depth and detail of a skilled reporter and the narrative grace of a master storyteller, Cynthia Anderson brings to life one of America's unlikeliest immigrant communities: the six thousand people from Sub-Saharan Africa who have made a home for themselves in one of the coldest states in the nation. In Home Now, she carefully strips away the politics surrounding Muslim refugees in the United States to reveal human beings whose relationships with each other are anything but foreign. These individuals are recognizable as mothers, daughters, fathers, and sons and recognizably American in their dreams of a better future."Paul Doiron, author of The Poacher's Son

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use