By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Local Knowledge

Further Essays In Interpretive Anthropology

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 4, 2008

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786723751

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 4, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Shrewd and often illuminating."—New York Times

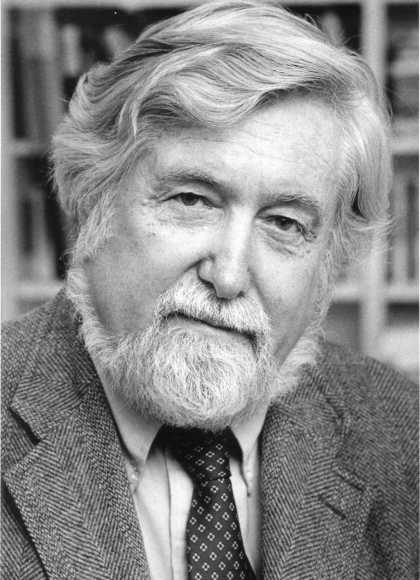

Over his storied career, Clifford Geertz pioneered ground-breaking approaches to anthropology, arguing that interpreting and analyzing cultural symbols was central to understanding a wide range of societies. In Local Knowledge, he revisits and expands the core ideas that reshaped an entire field.

In chapters covering everything from art in Renaissance Italy to political pageantry in Java, Geertz deepens our understanding of human societies though the intimacies of “local knowledge.” Geertz explores the very meaning of culture and the importance of shared symbolism as a means of understanding the world. Through his signature analysis and undeniable, intellectual rigor, this foundational text invites readers to better understand how culture produces the ideas and systems that populate our everyday lives.

-

“Shrewd and often illuminating."New York Times

-

"As an anthropologist, philosopher, political scientist, literary critic, and all-around, all-star intellectual, Clifford Geertz helped a vast public make sense of the human condition."New York Review of Books

-

"Clifford Geertz [was] an anthropologist whose imaginative studies of cultural groups from other countries changed the intellectual underpinnings of anthropology and other social sciences.... Dr. Geertz brought a distinctly literary sensibility to the study of anthropology with his sophisticated prose and vivid descriptions of social customs abroad.... Dr. Geertz's ornate, allusive accounts of other cultures came to define a new field of study called ethnography."Washington Post

-

"Clifford Geertz is one of those rare scholars: the thinking person's liberal, who spurns easy banalities."Guardian

-

"One of the most articulate cultural anthropologists of this generation. Geertz has consistently attempted to clarify the meaning of 'culture' and to relate that concept to the actual behavior of individuals and groups."Contemporary Sociology