Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

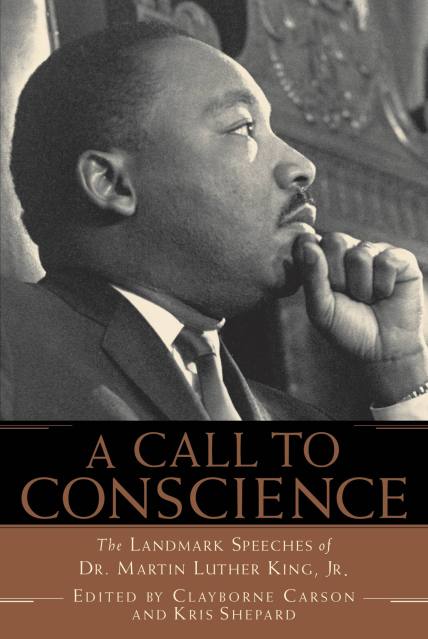

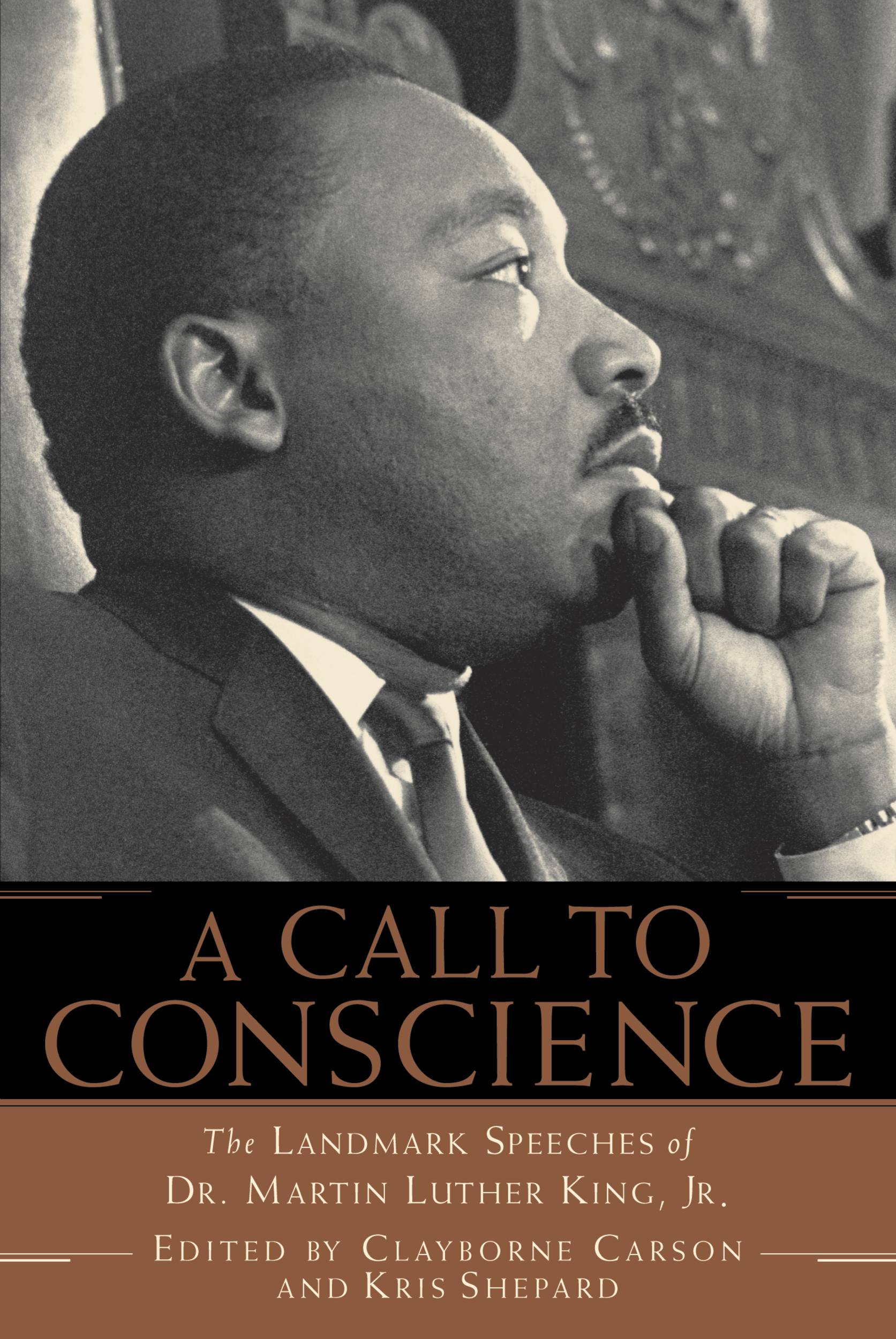

A Call to Conscience

The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Contributors

By Kris Shepard

Introduction by Andrew Young

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 15, 2001. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A powerful collection of the most essential speeches from famed social activist and key civil rights figure Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

This companion volume to A Knock At Midnight: Inspiration from the Great Sermons of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. includes the text of his most well-known oration, “I Have a Dream”, his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, and Beyond Vietnam, a powerful plea to end the ongoing conflict. Includes contributions from Rosa Parks, Aretha Franklin, the Dalai Lama, and many others.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 15, 2001

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780759520080

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use