Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

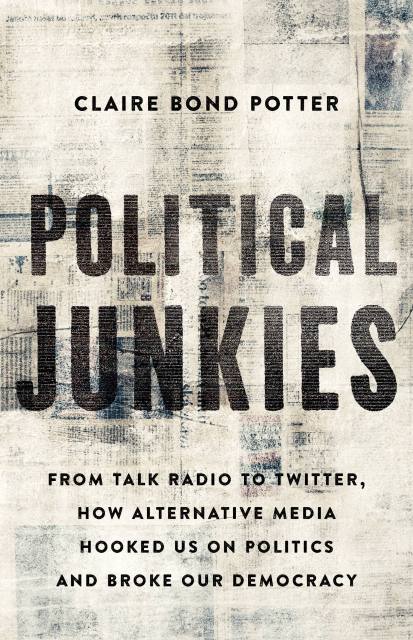

Political Junkies

From Talk Radio to Twitter, How Alternative Media Hooked Us on Politics and Broke Our Democracy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541645004

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A wide-ranging history of seventy years of change in political media, and how it transformed — and fractured — American politics

With fake news on Facebook, trolls on Twitter, and viral outrage everywhere, it’s easy to believe that the internet changed politics entirely. In Political Junkies, historian Claire Bond Potter shows otherwise, revealing the roots of today’s dysfunction by situating online politics in a longer history of alternative political media.

From independent newsletters in the 1950s to talk radio in the 1970s to cable television in the 1980s, pioneers on the left and right developed alternative media outlets that made politics more popular, and ultimately, more partisan. When campaign operatives took up e-mail, blogging, and social media, they only supercharged these trends. At a time when political engagement has never been greater and trust has never been lower, Political Junkies is essential reading for understanding how we got here.