By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

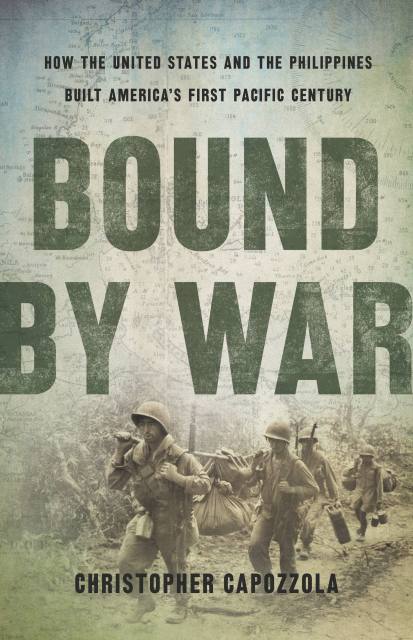

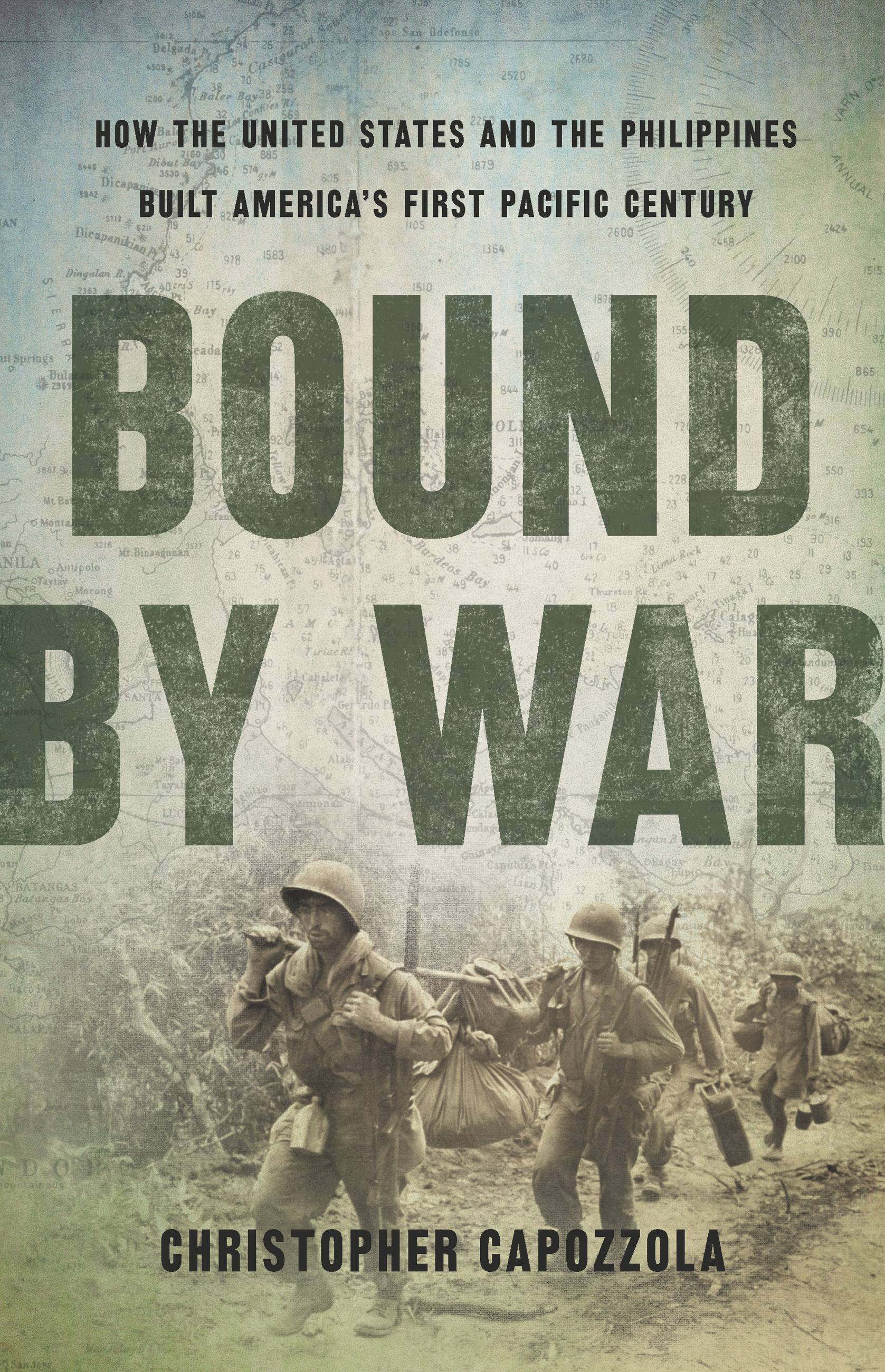

Bound by War

How the United States and the Philippines Built America's First Pacific Century

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 28, 2020

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541618268

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 28, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A sweeping history of America’s long and fateful military relationship with the Philippines amid a century of Pacific warfare

Ever since US troops occupied the Philippines in 1898, generations of Filipinos have served in and alongside the US armed forces. In Bound by War, historian Christopher Capozzola reveals this forgotten history, showing how war and military service forged an enduring, yet fraught, alliance between Americans and Filipinos.

As the US military expanded in Asia, American forces confronted their Pacific rivals from Philippine bases. And from the colonial-era Philippine Scouts to post-9/11 contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan, Filipinos were crucial partners in the exercise of US power. Their service reshaped Philippine society and politics and brought thousands of Filipinos to America.

Telling the epic story of a century of conflict and migration, Bound by War is a fresh, definitive portrait of this uneven partnership and the two nations it transformed.