By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

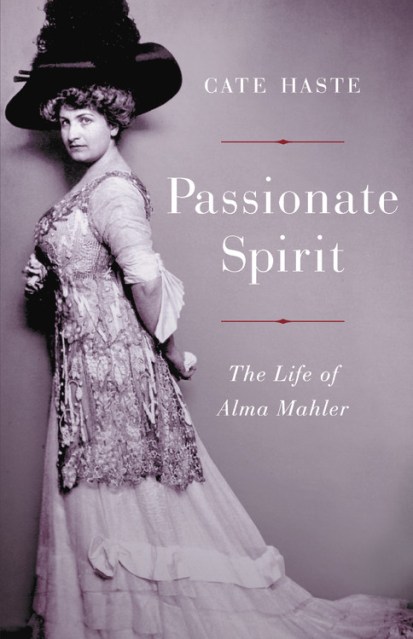

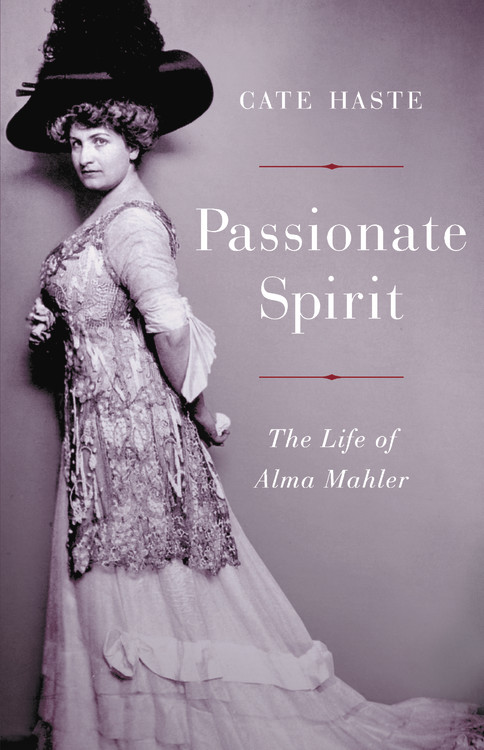

Passionate Spirit

The Life of Alma Mahler

Contributors

By Cate Haste

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2019

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096718

Price

$32.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A new biography of Alma Mahler (1879-1964), revealing a woman determined to wield power in a world that denied her agency

History has long vilified Alma Mahler. Critics accused her of distracting Gustav Mahler from his work, and her passionate love affairs shocked her peers. Drawing on Alma’s vivid, sensual, and overlooked diaries, biographer Cate Haste recounts the untold and far more sympathetic story of this ambitious and talented woman. Though she dreamed of being the first woman to compose a famous opera, Alma was stifled by traditional social values. Eventually, she put her own dreams aside and wielded power and influence the only way she could, by supporting the art of more famous men. She worked alongside them and gained credit as their muse, commanding their love and demanding their respect.

Passionate Spirit restores vibrant humanity to a woman time turned into a caricature, providing an important correction to a history where systemic sexism has long erased women of talent.

-

"Like the stories of most notorious women, Alma Mahler's is one of sex and power...Was she an artist stunted by society's restrictions on women who channeled her genius to become the inspiration for the men she consorted with? Or was she a grandiose groupie, expropriating the fame of her husbands and lovers? In a new biography, Passionate Spirit, Cate Haste leans toward the former view."New York Review of Books

-

"In this sympathetic, engrossing biography of Viennese socialite and composer Alma Mahler, Haste traces Mahler's struggle to find equilibrium among her men (all creative geniuses), her erotic desires, and her own musical ambition."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Haste portrays Alma Mahler in all her whirring and feverish complexity, and the result is as engrossing as it is jaw-dropping."The Paris Review

-

"A well-rounded portrait of an imperious woman and her eventful life."Kirkus Reviews

-

"In this meticulously researched and absorbing biography... Mahler is depicted as a woman who not only facilitated the creative pursuits of her husbands and lovers, but was an intellectual and creative force in her own right."Hannah Beckerman, The Guardian

-

"Considering the sexism of the 19th and 20th centuries, Alma Mahler's status as a 'muse' can be understood as a strategic attempt to signal her own talents to the world. Haste presents a necessary update and reframing of Mahler's life and legacy."Library Journal

-

"Haste... gives Alma room to romp, drawing on unpublished diary entries and memoirs (along with a trove of previous accounts) to reveal the full Alma in all her maddening, intoxicating, intimidating variety.... This delectable biography assembles the awesome elements of Alma's breathtaking life's work; it answers the questions of who, where, and when; yet the question of how this one woman succeeded in filling her canvas so magisterially remains as tantalizing and mysterious as Alma herself."Liesl Schillinger, Airmail

-

"What does it mean to be a muse who is looking for her own? That is the question Alma (whose first husband is the composer Gustav Mahler) attempts to answer over the course of her life, marked by bouts of happiness and tragedy... Haste uses previously unpublished letters and diaries to restore Alma Mahler's place among the central figures of the Viennese fin de siècle."LitHub

-

"Fascinating... Haste paints a portrait of a woman who was born to triumph, not surrender."Harper's Bazaar

-

"Seductively accessible...Written in elegant, lucid prose, [Passionate Spirit] is a treasure trove of European cultural riches and scandalous intrigue."The Economist

-

"The Alma of Passionate Spirit is a more sympathetic creature than the monster of previous biographies... Cate Haste has wisely forsaken the harsh judgmental tone so often used about Alma, and corrected significant errors."The Spectator

-

"[Alma Mahler] does burst forth here with appealing force... Haste make a strong case for us to view her subject with more compassion."TheTimes

-

"Lively, well illustrated, and enjoyably juicy."Financial Times

-

"For the fiercest of fierce women on your gift list, look for Passionate Spirit: The Life of Alma Mahler, by Cate Haste. It's the story of Mahler, wife of the artist, who was also the first woman to write an opera at a time when women were supposed to be shadows of their husbands."Terri Schlichenmeyer