By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

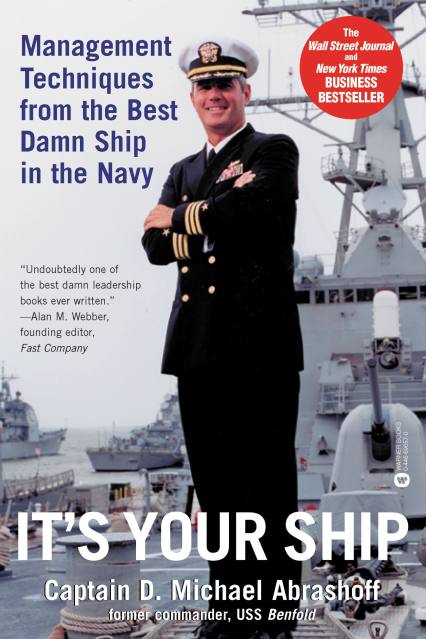

It’s Your Ship

Management Techniques from the Best Damn Ship in the Navy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2007

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446535533

Prices

- Sale Price $3.99

- Regular Price $16.99

- Discount (77% off)

Prices

- Sale Price $3.99 CAD

- Regular Price $21.99 CAD

- Discount (82% off)

Format

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When Captain Abrashoff took over as commander of USS Benfold, it was like a business that had all the latest technology but only some of the productivity. Knowing that responsibility for improving performance rested with him, he realized he had to improve his own leadership skills before he could improve his ship. Within months, he created a crew of confident and inspired problem-solvers eager to take the initiative and responsibility for their actions. The slogan on board became “It’s your ship,” and Benfold was soon recognized far and wide as a model of naval efficiency. How did Abrashoff do it? Against the backdrop of today’s United States Navy, Abrashoff shares his secrets of successful management including:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use