Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

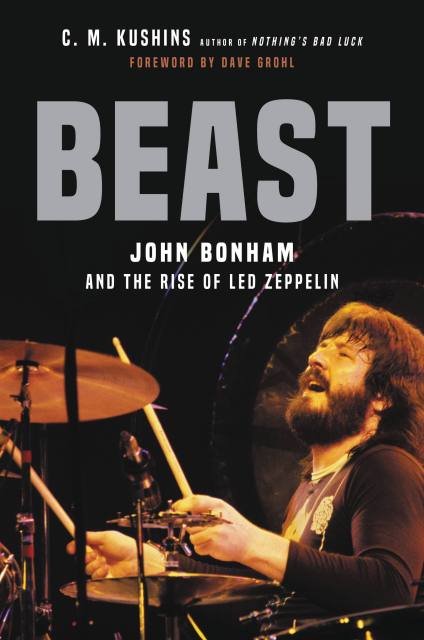

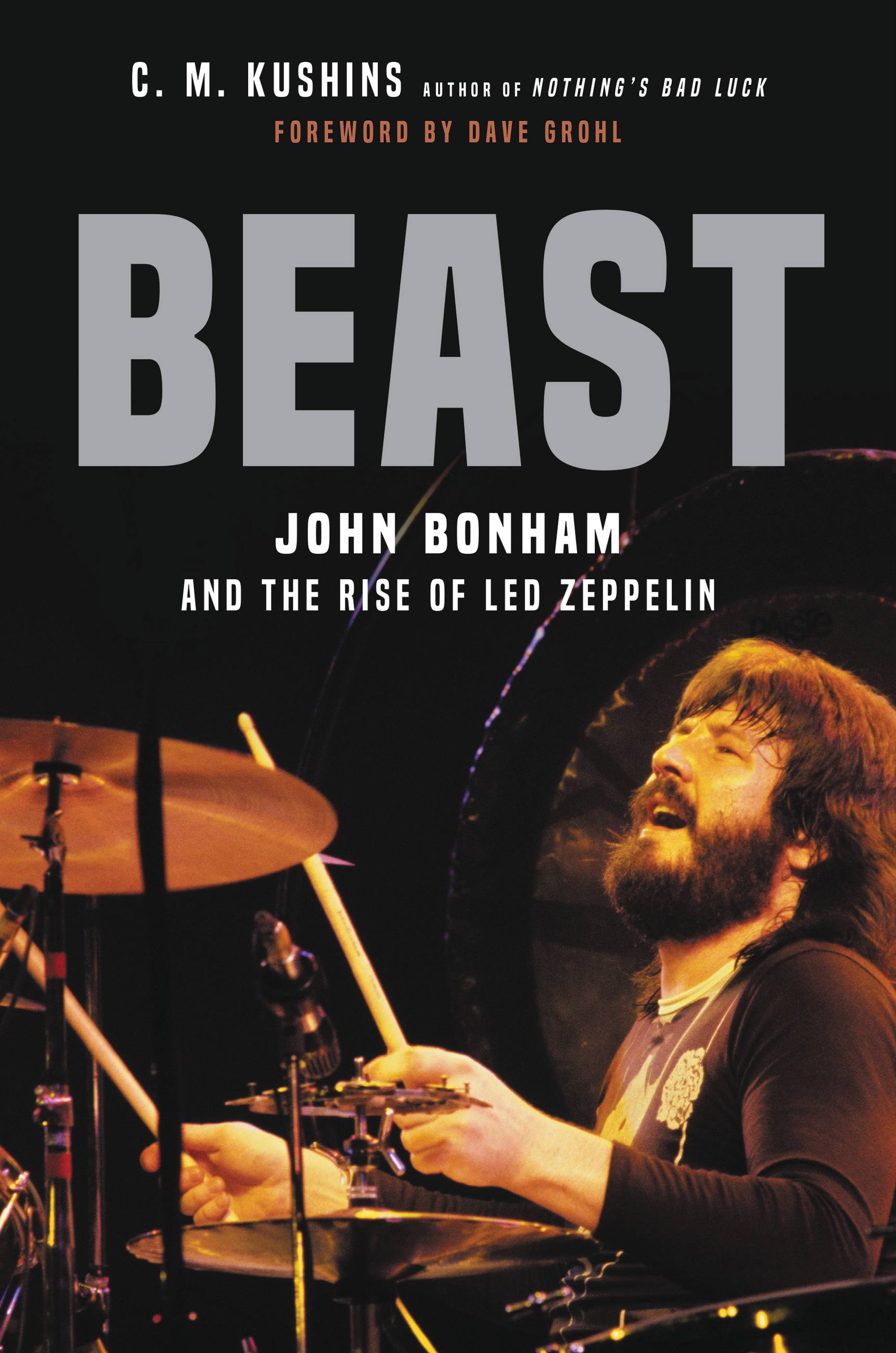

Beast

John Bonham and the Rise of Led Zeppelin

Contributors

Foreword by Dave Grohl

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 7, 2021

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306846670

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 7, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

John Bonham is considered by many to be one of the greatest drummers of all time. He was recruited to join the band who would eventually become known as Led Zeppelin–and before the year was out, Bonham and his bandmates would become the richest rock band in the world.

Throughout the 1970s, Led Zeppelin reached new heights of commercial and critical success, making them one of the most influential groups of the era, both in musical style and in their approach towards the workings of the entertainment industry. In September of 1980, Bonham–plagued by alcoholism, anxiety, and the after-effects of years of excess–was found dead by his bandmates.

As Adam Budofsky, managing editor of Modern Drummer, explains, "If the king of rock 'n' roll was Elvis Presley, then the king of rock drumming was certainly John Bonham."

-

"C.M. Kushins gives us a wild, behind-the-scenes look at one of the greatest rock bands ever, and brings John ‘Bonzo’ Bonham back to life in this well-written rock classic."Peter Leonard, Bestselling Author of Voices of the Dead