By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

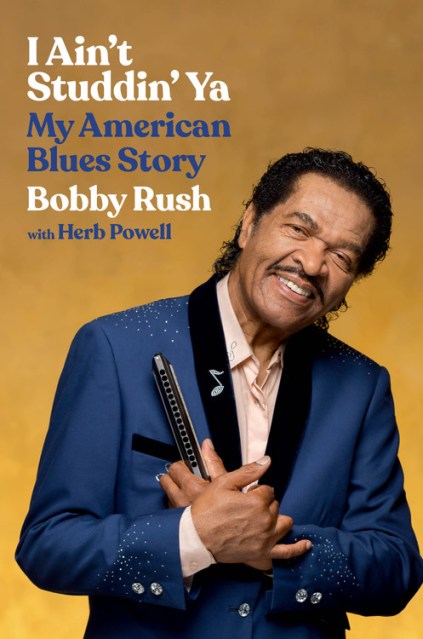

I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya

My American Blues Story

Contributors

By Bobby Rush

With Herb Powell

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 22, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306874802

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 22, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Experience music history with this memoir by one of the last of the genuine old school Blues and R&B legends, the Grammy-winning dynamic showman Bobby Rush.

This memoir charts the extraordinary rise to fame of living blues legend, Bobby Rush. Born Emmett Ellis, Jr. in Homer, Louisiana, he adopted the stage name Bobby Rush out of respect for his father, a pastor. As a teenager, Rush acquired his first real guitar and started playing in juke joints in Little Rock, Arkansas, donning a fake mustache to trick club owners into thinking he was old enough to gain entry. He led his first band in Arkansas between Little Rock and Pine Bluff in the 1950s. It was there he first had Elmore James play in his band. Rush later relocated to Chicago to pursue his musical career and started to work with Earl Hooker, Luther Allison, and Freddie King, and sat in with many of his musical heroes, such as Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed and Little Walter. Rush eventually began leading his own band in the 1960s, crafting his own distinct style of funky blues, and recording a succession of singles for various labels. It wasn’t until the early 1970s that Rush finally scored a hit with “Chicken Heads.” More recordings followed, including an album which went on to be listed in the Top 10 blues albums of the 1970s by Rolling Stone and a handful of regional jukebox favorites including “Sue” and “I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya.”

And Rush’s career shows no signs of slowing down now. The man once beloved for performing in local jukejoints is now headlining major music/blues festivals, clubs, and theaters across the U.S. and as far as Japan and Australia. At age eighty-six, he is still on the road for over 200 days a year. His lifelong hectic tour schedule has earned him the affectionate title “King of the Chitlin’ Circuit,” from Rolling Stone. In 2007, he earned the distinction of being the first blues artist to play at the Great Wall of China. His renowned stage act features his famed shake dancers, who personify his funky blues and his ribald sense of humor. He was featured in Martin Scorcese’s The Blues docuseries on PBS, a documentary film called Take Me to the River, performed with Dan Aykroyd on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, and most recently had a cameo in the Golden Globe nominated Netflix film, Dolemite Is My Name, starring Eddie Murphy. He was recently given the highest Blues Music Award honor of B.B. King Entertainer of the Year. His songs have also been featured in TV shows and films including HBO’s Ballers and major motion pictures like Black Snake Moan, starring Samuel L. Jackson.

Considered by many to be the greatest bluesman currently performing, this book will give readers unparalleled access into the man, the myth, the legend: Bobby Rush.

This memoir charts the extraordinary rise to fame of living blues legend, Bobby Rush. Born Emmett Ellis, Jr. in Homer, Louisiana, he adopted the stage name Bobby Rush out of respect for his father, a pastor. As a teenager, Rush acquired his first real guitar and started playing in juke joints in Little Rock, Arkansas, donning a fake mustache to trick club owners into thinking he was old enough to gain entry. He led his first band in Arkansas between Little Rock and Pine Bluff in the 1950s. It was there he first had Elmore James play in his band. Rush later relocated to Chicago to pursue his musical career and started to work with Earl Hooker, Luther Allison, and Freddie King, and sat in with many of his musical heroes, such as Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed and Little Walter. Rush eventually began leading his own band in the 1960s, crafting his own distinct style of funky blues, and recording a succession of singles for various labels. It wasn’t until the early 1970s that Rush finally scored a hit with “Chicken Heads.” More recordings followed, including an album which went on to be listed in the Top 10 blues albums of the 1970s by Rolling Stone and a handful of regional jukebox favorites including “Sue” and “I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya.”

And Rush’s career shows no signs of slowing down now. The man once beloved for performing in local jukejoints is now headlining major music/blues festivals, clubs, and theaters across the U.S. and as far as Japan and Australia. At age eighty-six, he is still on the road for over 200 days a year. His lifelong hectic tour schedule has earned him the affectionate title “King of the Chitlin’ Circuit,” from Rolling Stone. In 2007, he earned the distinction of being the first blues artist to play at the Great Wall of China. His renowned stage act features his famed shake dancers, who personify his funky blues and his ribald sense of humor. He was featured in Martin Scorcese’s The Blues docuseries on PBS, a documentary film called Take Me to the River, performed with Dan Aykroyd on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, and most recently had a cameo in the Golden Globe nominated Netflix film, Dolemite Is My Name, starring Eddie Murphy. He was recently given the highest Blues Music Award honor of B.B. King Entertainer of the Year. His songs have also been featured in TV shows and films including HBO’s Ballers and major motion pictures like Black Snake Moan, starring Samuel L. Jackson.

Considered by many to be the greatest bluesman currently performing, this book will give readers unparalleled access into the man, the myth, the legend: Bobby Rush.

-

“I’ve had the pleasure of knowing my friend Bobby for over forty years. He’s a born entertainer and a riot.”Mavis Staples

-

“Merely living and surviving nine decades would be marked as a huge accomplishment for anyone but then pack in thousands of nights filled with music, dancing, laughter, raucousness, professionalism, showmanship, all done with passion plus compassion and you have the life of Bobby Rush. This book is a must read for all serious followers of the American Rhythm and Blues cultural explosion by one of its extant founders.”Dan Aykroyd

-

“Bobby Rush’s I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya could be called ‘the spark of stayin' in the moment.’ Bobby’s indefatigable spirit and energy leap from the page of this delightful chronicle of a life well lived, and he is always in the moment. Bobby may be the only bluesman alive who can speak of a personal journey that extends from picking cotton in his youth to an active recording and performing career in 2021. Bobby personally knew many of the mythic artists who we think of when we explore the history of the blues. I recommend this book to any lover of the blues and any lover a good story.”Jerry Harrison, founding member of Talking Heads

-

“It’s Bobby Rush! Bobby is the real deal with an investment of a lifetime of raw effort and true talent. It's made Bobby Rush the overnight sensation he was destined to become. This is it!”Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top

-

"Bobby Rush rode the blues from the southern farm to the northern city and then back home, becoming one of the kings of the modern Chitlin Circuit. He’s got a great memory, a sharp eye for details, and he’s always been a great entertainer, so I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya is full of great tales. Reading this is like listening to Bobby Rush talk us through his life, which is a great contemporary blues story."Robert Gordon, author of It Came from Memphis and Can’t Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters

-

“Bobby Rush is one of my favorite performers, and this book is as smart, funny, and soulful as his shows. He is also a profoundly thoughtful man and his warmth and wisdom come through on every page. Rush has been everywhere, known everyone, and is the greatest road warrior on the blues scene. He has eighty years of wonderful stories, and I'm already waiting for volume two.”Elijah Wald, author of Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues and How the Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music

-

"Rush’s memoir... is frank about many things, including the reason he’s received so many standing ovations in recent years."New York Times

-

"Rush never fails to put on an electrifying performance, and his entertaining autobiography is no exception. Reading this is like sitting backstage with Rush listening to him tell story after story of his life and long career."No Depression

-

"In I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya, Rush gives readers intimate access into his life and career like never before.... Bobby Rush is the American success story. Hail to the King!"American Blues Scene

-

“In addition to its entertainment and cultural value, Rush’s memoir holds the wisdom he’s gained during a long and active life.”The Advocate

-

"A fascinating story well told... A richly detailed account of a bluesman’s full life."Kirkus Reviews

-

"[I Ain't Studdin' Ya features] short, conversational chapters written in a leisurely, friendly, and down-home style.”Booklist

-

"I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya reads like the raw and mostly uncut version of how Emmett Ellis, Jr. became Bobby Rush."Jackson Advocate Online

-

"In I Ain’t Studdin' Ya, Rush recalls with great detail his lifelong journey in the music business beginning with his father pulling out an old harmonica from his overalls pocket where a young Rush instantly got hooked on the blues... Rush’s determination and hard work is admirable and evident in his life story."Houston Press

-

A "SUMMER MUST-READ" [Slate, Chicago Tribune]

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use