By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

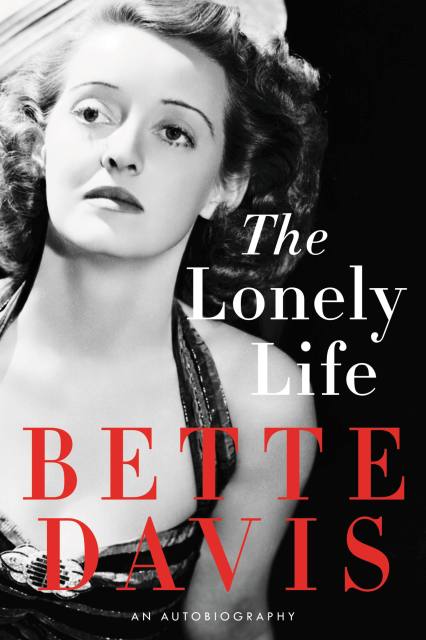

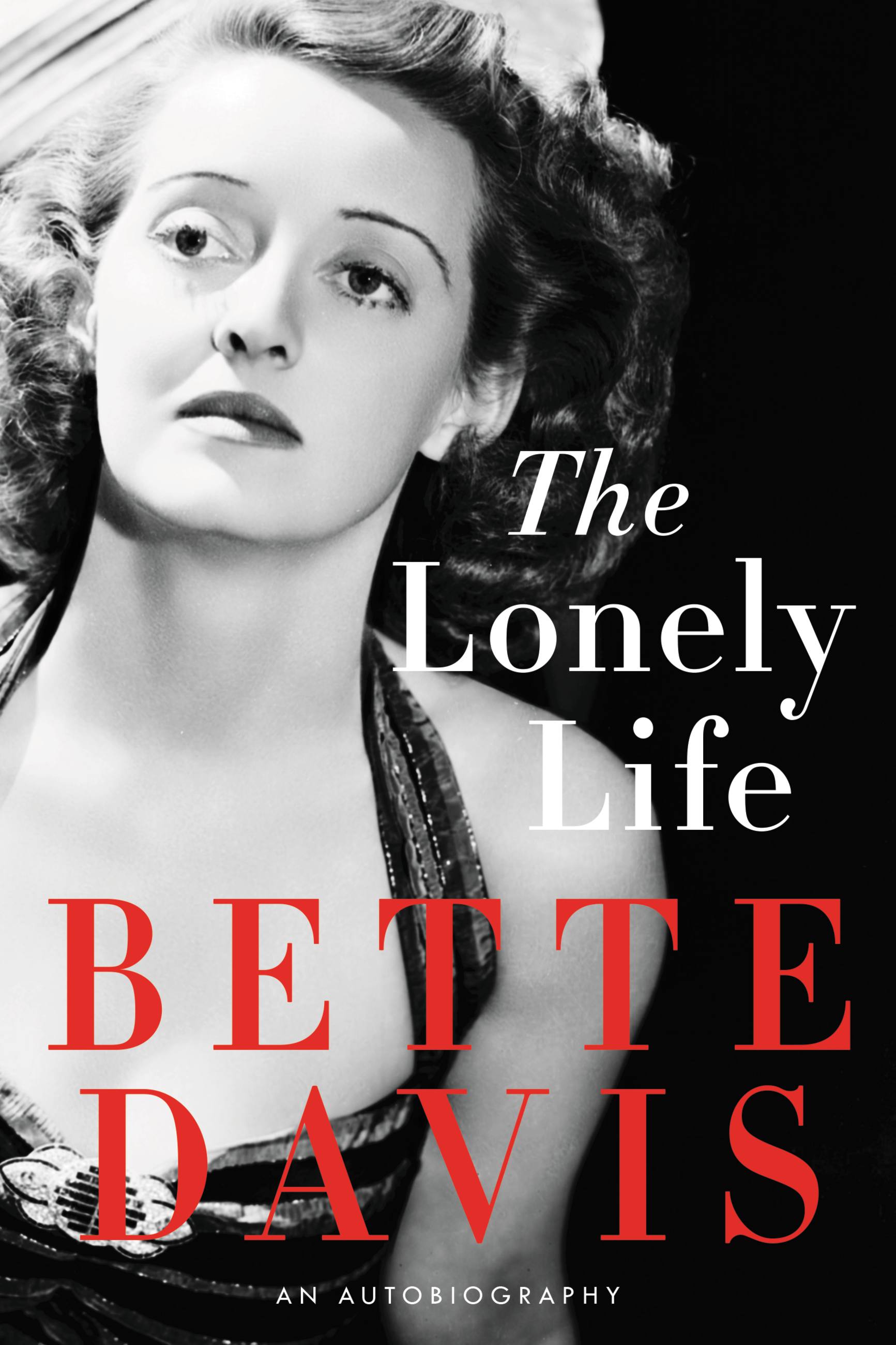

The Lonely Life

An Autobiography

Contributors

By Bette Davis

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 4, 2017

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316441292

Price

$5.99Price

$7.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (Digital original) $5.99 $7.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 4, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As Davis says in the opening lines of her classic memoir: “I have always been driven by some distant music–a battle hymn, no doubt–for I have been at war from the beginning. I rode into the field with sword gleaming and standard flying. I was going to conquer the world.” A bold, unapologetic book by a unique and formidable woman, The Lonely Life details the first fifty-plus years of Davis’s life–her Yankee childhood, her rise to stardom in Hollywood, the birth of her beloved children, and the uncompromising choices she made along the way to succeed. The book was updated with new material in the 1980s, bringing the story up to the end of Davis’s life–all the heartbreak, all the drama, and all the love she experienced at every stage of her extraordinary life.

The Lonely Life proves conclusively that the legendary image of Bette Davis is not a fable but a marvelous reality.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use