By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

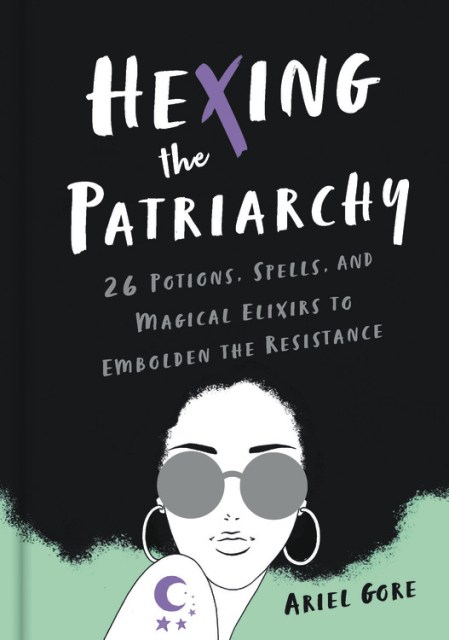

Hexing the Patriarchy

26 Potions, Spells, and Magical Elixirs to Embolden the Resistance

Contributors

By Ariel Gore

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580058742

Price

$28.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A magical guide to subverting manboy power, one spell at a time

Skeptics might think witchcraft is nothing more than a fad, but make no mistake: modern witches aren’t playing around. Today’s wizarding women are raising hell, exorcising haters, and revving up to fight fire with a fierce inferno of magical outrage.

Magic has always been a weapon of the disenfranchised, and in Hexing the Patriarchy, author Ariel Gore offers a playbook for the feminist uprising. Full of incantations, enchantments, rituals, and witchy wisdom designed protect women and bring down The Man, readers will learn how to . . .

Magic has always been a weapon of the disenfranchised, and in Hexing the Patriarchy, author Ariel Gore offers a playbook for the feminist uprising. Full of incantations, enchantments, rituals, and witchy wisdom designed protect women and bring down The Man, readers will learn how to . . .

- Make salt scrubs to wash away patriarchal bullshit

- Mix potions to run abusive liars out of town

- Use their bare hands and feet to vanquish bro culture

- Conjure dead relatives to help smash the system

. . . and more.

From summoning Ancestors to leveraging the Zodiac, these twenty-six alphabetically inspired spells are ready-made recipes for toppling the patriarchy with a dangerously divine, they-never-saw-it-coming power.

-

"It's time to conjure. Ariel Gore's Hexing the Patriarchy is a call to arms--if by 'arms' we mean hearts and guts and brains and twinkle parts against brutality. This book is about the spells, incantations, and storytelling we need to bring ourselves back to life. This book is a magical field guide that will set the crap that needs to burn on fire, and compost the living shit out of the wrong world toward revolution, revelation, reformation, and release. I'm all in."Lidia Yuknavitch, bestselling author of The Misfit's Manifesto, The Book of Joan, The Chronology of Water, and more

-

"Employing fierce metaphysics, creativity, humor, and pure badass conjuring, Ariel Gore's magical, majestic Hexing the Patriarchy is a practical field guide to fixing what's wrong the world, one earth-loving, mama-empowering, patriarchy-squashing hex at a time. Just holding this book in my hands makes me feel giddy with hope."Karen Karbo, author of In Praise of Difficult Women

-

"Ariel Gore has given us . . . the tools and the nerve to be magic. Her cauldron is for every stepped-on and marginalized being to add to and shine on. Gore knows that in the collective we are free from our masters--while one can be free in their mind, those who actualize their potential as a tribe might save what's left of our world. Hexing the Patriarchy is an anti-fascism tool that belongs in our feminist libraries and medicine chests to aid what ails you through this fight."Sophia Shalmiyev, author of Mother Winter

-

"I endorse Ariel Gore's book, which covers everything from wholesome light witchcraft for health to what you gotta do to punch your enemy in the throat. The spell I most needed, and used, was 'Be Your Own Muse.' If you've ever been a muse to an m-a-n, especially a certain bass player, you know what fresh hell it was. Thank you, Ariel Gore."Jennifer Blowdryer, journalist and punk music artist

-

"We have needed this book for centuries! Ariel Gore, in all her witchy-smart goodness, will inspire you, bolster you, lift you up, remind you who you are, and show you how to find your power in a world that is constantly trying to keep you from having it. And, she does so in a way that is good-natured and endlessly fun to read. I expect to pick up this book and practice the spells throughout the rest of my life -- unless all of you buy this book and do the spells with me, and we collectively do away with patriarchy for good."Kerry Cohen, author of Lush: A Memoir and Loose Girl: A Memoir of Promiscuity

-

"This alphabetized witch primer had me at 'B: binding spells for grabby assholes'!"Jennifer Baumgardner, author of Manifesta and F 'Em