Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

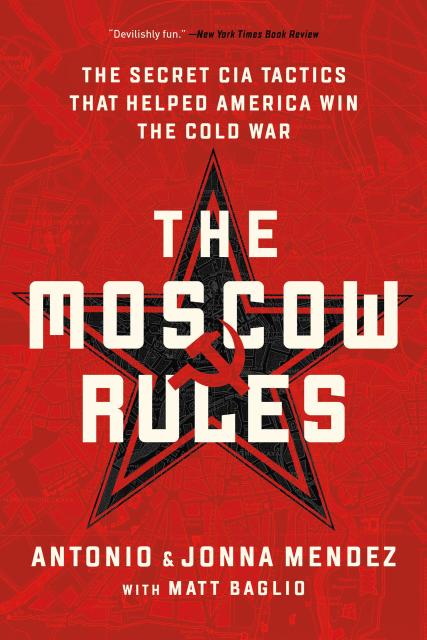

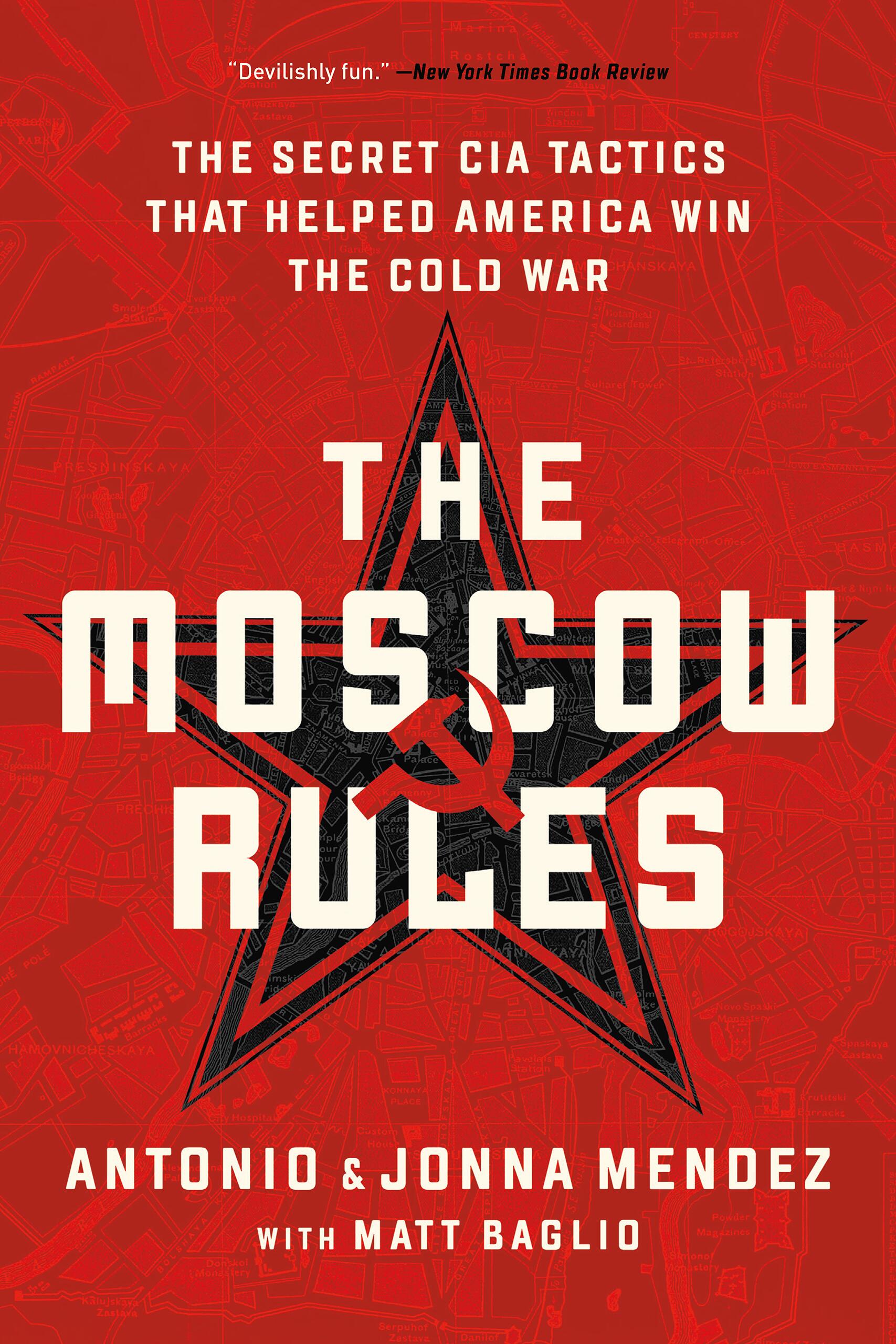

The Moscow Rules

The Secret CIA Tactics That Helped America Win the Cold War

Contributors

By Jonna Mendez

With Matt Baglio

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 19, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541762183

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Digital download $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 19, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Two legendary former CIA operatives reveal the tactics they developed to survive the Cold War in Moscow and turn the odds in America’s favor

“Devilishly fun.” —New York Times Book Review

Antonio and Jonna Mendez were CIA technical operations officers in Moscow during the dangerous final years of the Cold War. Soviets kept files on all foreigners, studied their patterns, and tapped their phones. Intelligence work was effectively impossible. The Soviet threat loomed larger than ever.

A vivid exposé that reads like a le Carré novel, The Moscow Rules sheds light on the brave collaborations between CIA operatives and Russian informants, and the innovative ways they avoided Soviet surveillance. As experts in disguise, Antonio and Jonna were instrumental in developing a series of tactics—from Hollywood-inspired identity swaps to an armory of James Bond–style gadgets—that allowed CIA officers to outmaneuver the KGB.

The Moscow Rules is the remarkable story of the undercover spies who risked everything for their country, and a tribute to the ingenuity that allowed them to succeed.

“Devilishly fun.” —New York Times Book Review

Antonio and Jonna Mendez were CIA technical operations officers in Moscow during the dangerous final years of the Cold War. Soviets kept files on all foreigners, studied their patterns, and tapped their phones. Intelligence work was effectively impossible. The Soviet threat loomed larger than ever.

A vivid exposé that reads like a le Carré novel, The Moscow Rules sheds light on the brave collaborations between CIA operatives and Russian informants, and the innovative ways they avoided Soviet surveillance. As experts in disguise, Antonio and Jonna were instrumental in developing a series of tactics—from Hollywood-inspired identity swaps to an armory of James Bond–style gadgets—that allowed CIA officers to outmaneuver the KGB.

The Moscow Rules is the remarkable story of the undercover spies who risked everything for their country, and a tribute to the ingenuity that allowed them to succeed.

Genre:

-

“The Moscow Rules is devilishly fun.”New York Times Book Review

-

“Opens a rare window into how the CIA works in the Russian capital.”NPR

-

“Few people have contributed more to helping the public better understand the reality of the intelligence business than former CIA officers Antonio and Jonna Mendez. . . . Their book is a reassuring testament to just how resourceful U.S. intelligence officers can be when faced with a determined and skillful adversary.”Military Review

-

“A gripping, interesting and relevant read . . . Reads like a spy novel yet tells a true tale of the darkest days of the espionage war largely fought between the CIA and the KGB.”Cipher Brief

-

“Jonna and Tony Mendez are American heroes. . . . This book is a gripping testimonial to their work.”George J. Tenet, New York Times bestselling author of At the Center of the Storm: My Years at the CIA

-

“If there was ever a single book which could sum up the dangers, heroism, inventiveness and intrepidity of the intelligence officers of the CIA it is The Moscow Rules. This final homage to one of the nation’s bravest patriots will be an instant bestseller. It is the real‑life spy thriller one can’t put down.”Malcolm Nance, New York Times bestselling author of The Plot to Destroy Democracy

-

“An insider’s look at CIA operations in Moscow, the most challenging operational city in the world, revealing the tradecraft precepts used to keep priceless assets productive against overwhelming KGB surveillance. Written by two of the people who created these breakthrough tactics, The Moscow Rules takes you every step of the way on the snowy streets of Moscow.”Jason Matthews, New York Times bestselling author of the Red Sparrow trilogy

-

“Intriguing true stories of the techniques of CIA spying on the dangerous front line of the Cold War.”Stella Rimington, former Director General of MI5, and author of At Risk

-

“Even inside the CIA, very few know the whole story of how the highest‑level CIA tradecraft was developed for use in Moscow. The legendary Tony and Jonna Mendez were a vital part of creating that tradecraft, and their riveting insider account is unlike any spy story that's ever been published.”Joe Weisberg, creator of The Americans, and author of Russia Upside Down

-

“A gripping read. Thanks to Tony Mendez’s extraordinary talent, the CIA was able to elude KGB surveillance to carry out high‑risk, high‑payoff operations with impunity—until tripped up by traitors within our own ranks. It’s all in this book—the good, the bad, and the ugly, unflinchingly revealed. Tony and his wife and coauthor, Jonna, were two of the stars from the Office of Technical Service, CIA’s version of James Bond's ‘Q,’ and key to so many of the agency’s successes—and nowhere more so than in Moscow during the Cold War.”Jack Downing, former Deputy Director for Operations, CIA

-

“Eye‑opening entertainment. Fans of le Carré and other spinners of secret‑agent tales will find this of considerable interest.”Kirkus