Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

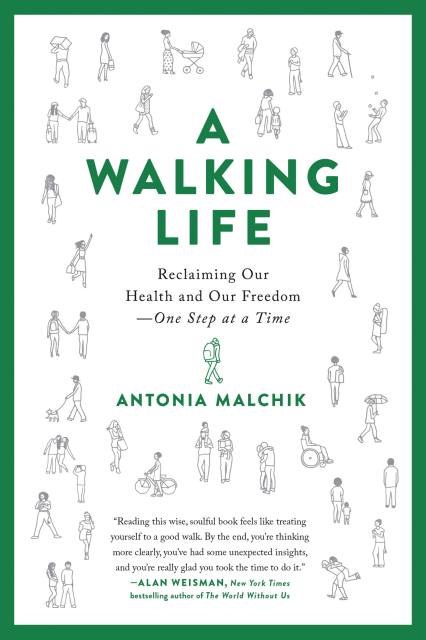

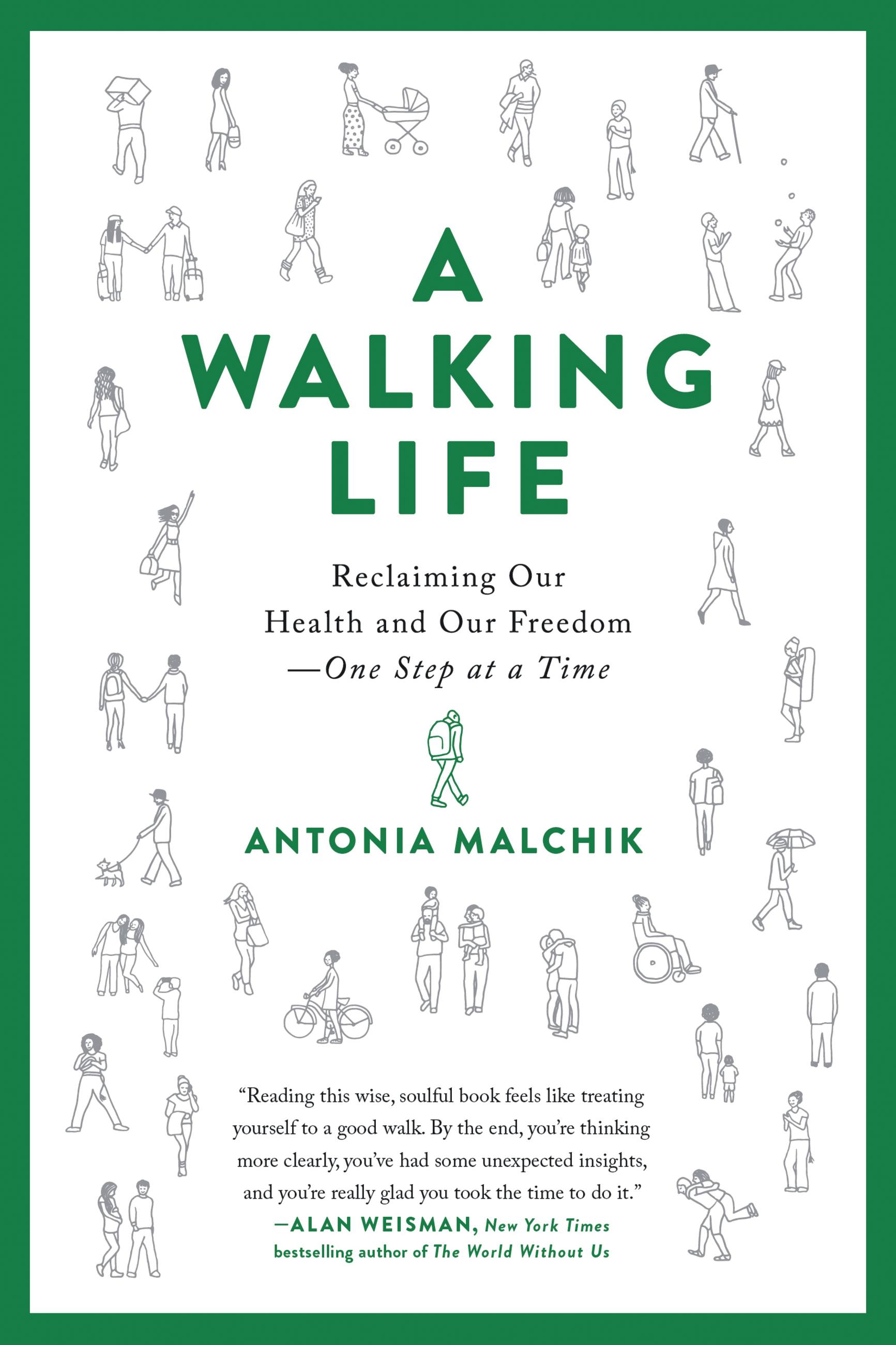

A Walking Life

Reclaiming Our Health and Our Freedom One Step at a Time

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 5, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780738234885

Price

$15.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 5, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For readers of On Trails, this is an incisive, utterly engaging exploration of walking: how it is fundamental to our being human, how we’ve designed it out of our lives, and how it is essential that we reembrace it.

“I’m going for a walk.” How often has this phrase been uttered by someone with a heart full of anger or sorrow? Or as an invitation, a precursor to a declaration of love? Our species and its predecessors have been bipedal walkers for at least six million years; by now, we take this seemingly arbitrary motion for granted. Yet how many of us still really walk in our everyday lives?

Driven by a combination of a car-centric culture and an insatiable thirst for productivity and efficiency, we’re spending more time sedentary and alone than we ever have before. If bipedal walking is truly what makes our species human, as paleoanthropologists claim, what does it mean that we are designing walking right out of our lives? Antonia Malchik asks essential questions at the center of humanity’s evolution and social structures: Who gets to walk, and where? How did we lose the right to walk, and what implications does that have for the strength of our communities, the future of democracy, and the pervasive loneliness of individual lives?

The loss of walking as an individual and a community act has the potential to destroy our deepest spiritual connections, our democratic society, our neighborhoods, and our freedom. But we can change the course of our mobility. And we need to. Delving into a wealth of science, history, and anecdote — from our deepest origins as hominins to our first steps as babies, to universal design and social infrastructure, A Walking Life shows exactly how walking is essential, how deeply reliant our brains and bodies are on this simple pedestrian act — and how we can reclaim it.

-

"Reading this wise, soulful book by Antonia Malchik feels like treating yourself to a good walk. By the end, you're thinking more clearly, you've had some unexpected insights, and you're really glad you took the time to do it."Alan Weisman, author of the New York Times bestseller The World Without Us and Countdown

-

"Antonia Malchik's walkabout reconnects us to what it means to be human -- finding community, citizenship, creativity, mental and physical health, and ultimately, freedom -- through the perambulation that distinguishes us from other creatures. This is an important book for our time: we must reincorporate walking in the fabric of our environments if we are to remain resilient to the challenges that face us."Wade Graham, author of Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World

-

"This charming and poignant book really brings home what it means to walk. Look no further for evidence of what we have forsaken by allowing so much of our country and planet to be reshaped, no longer around the human stride, but around the demands of a two-ton steel carapace that, for only 20 percent of our income, grants us obesity, asthma, daily carnage, unending traffic, and climate change."Jeff Speck, city planner and author Walkable City Rules

-

"The overall message is eye-opening, revealing the somber reality of our car-centric world but also inspiring a desire to reconnect with our primeval desire to wander on our own two feet."Booklist

-

"Readers interested in green living and libraries that support ecology and urban studies programs will want this far-reaching book about how to maintain a sustainable lifestyle."Library Journal

-

"A travel writer who now lives in her native Montana after decades of more urban life, Malchik hasn't simply written a self-help book on the physical and psychological benefits of walking, though there is plenty of that here. The author also delivers a manifesto that involves urban planning, technology, political protest, the environment, and the future of the planet. Humans were not only designed to walk, she writes; they are all but defined by their bipedal nature. [...] She also explores the ramifications of refugees walking hundreds of miles for asylum, protestors mobilizing in the thousands for political action, and pilgrims undertaking long journeys by foot for spiritual reasons. (She finds walking meditation more beneficial than sitting meditation.) If we walked more often, we'd feel better, think more creatively, suffer less depression, have more connections as a community, breathe cleaner air, and have a more profound understanding of our place on the planet...[Malchik] makes a convincing plea for better balance."Kirkus

-

"No wonder, then, so many writers have, of late, taken to the page to give encomiums to walking. Few do it as warmly as Antonia Malchik, who reminds us in A Walking Life that walking is about so much more than movement--our footfalls, she demonstrates, are about longing, freedom, connection, belonging, and home. ... Reading her book is tantamount to taking a walk with a generous friend whose curiosity and hope fills you with the compulsion to walk and open yourself to the world and its infinite stories."Garnette Cadogan, Literary Hub