By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

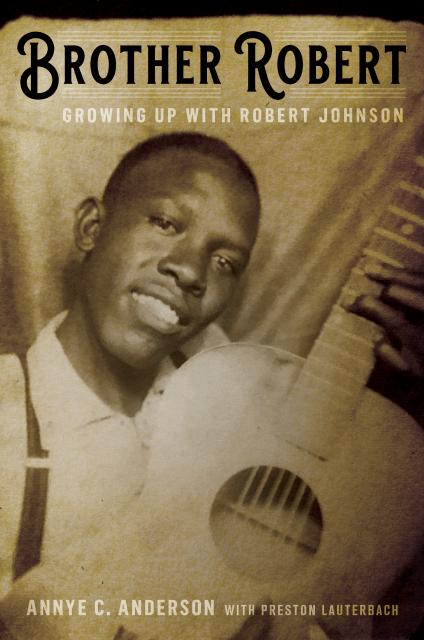

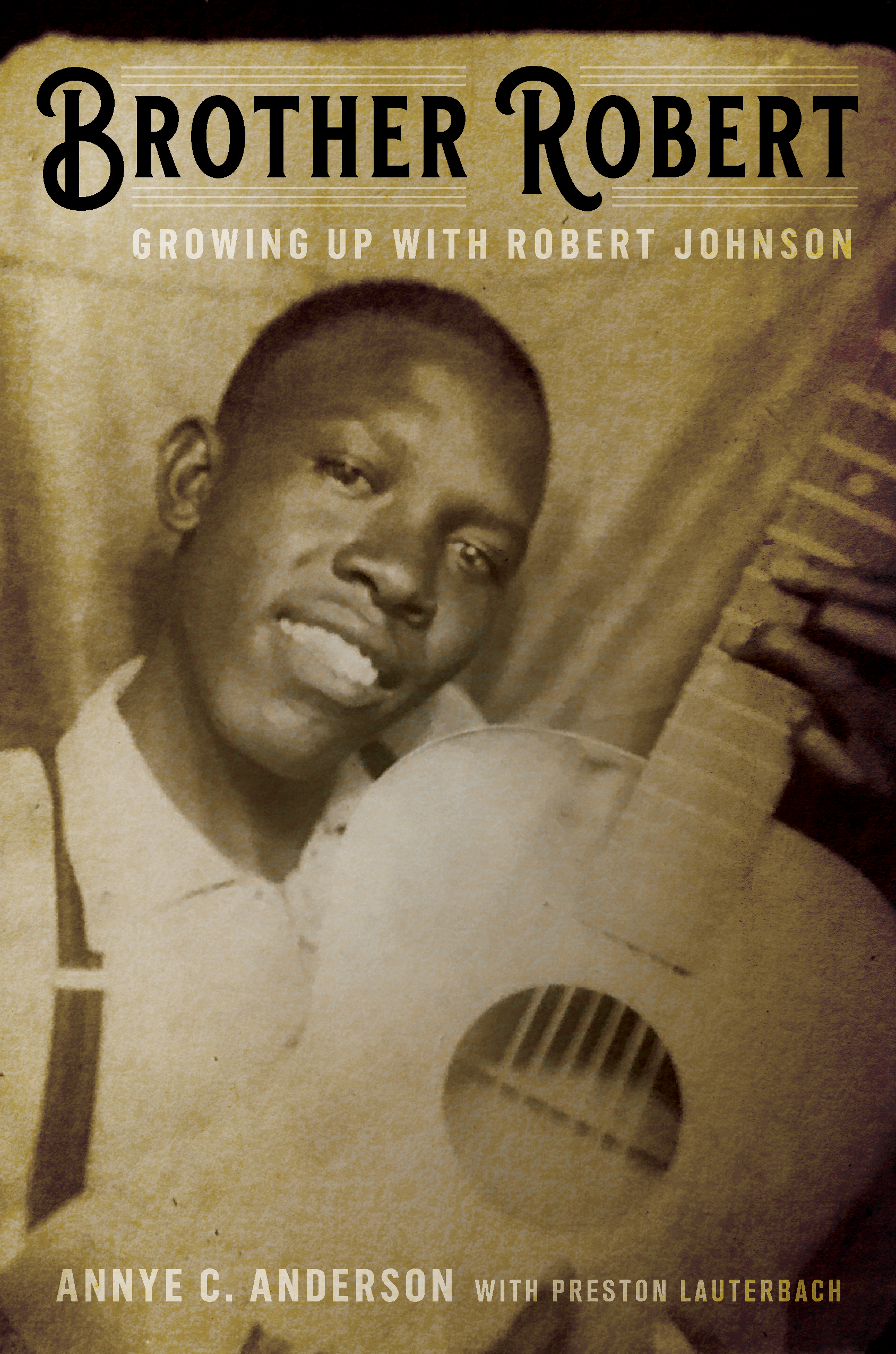

Brother Robert

Growing Up with Robert Johnson

Contributors

With Preston Lauterbach

Foreword by Elijah Wald

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 9, 2020

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306845260

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 9, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“[Brother Robert} book does much to pull the blues master out of the fog of myth.”—Rolling Stone

An intimate memoir by blues legend Robert Johnson’s stepsister, including new details about his family, music, influences, tragic death, and musical afterlife

Though Robert Johnson was only twenty-seven years young and relatively unknown at the time of his tragic death in 1938, his enduring recordings have solidified his status as a progenitor of the Delta blues style. And yet, while his music has retained the steadfast devotion of modern listeners, much remains unknown about the man who penned and played these timeless tunes. Few people alive today actually remember what Johnson was really like, and those who do have largely upheld their silence-until now.

In Brother Robert, nonagenarian Annye C. Anderson sheds new light on a real-life figure largely obscured by his own legend: her kind and incredibly talented stepbrother, Robert Johnson. This book chronicles Johnson’s unconventional path to stardom, from the harrowing story behind his illegitimate birth, to his first strum of the guitar on Anderson’s father’s knee, to the genre-defining recordings that would one day secure his legacy. Along the way, readers are gifted not only with Anderson’s personal anecdotes, but with colorful recollections passed down to Anderson by members of their family-the people who knew Johnson best. Readers also learn about the contours of his working life in Memphis, never-before-disclosed details about his romantic history, and all of Johnson’s favorite things, from foods and entertainers to brands of tobacco and pomade. Together, these stories don’t just bring the mythologized Johnson back down to earth; they preserve both his memory and his integrity.

For decades, Anderson and her family have ignored the tall tales of Johnson “selling his soul to the devil” and the speculative to fictionalized accounts of his life that passed for biography. Brother Robert is here to set the record straight. Featuring a foreword by Elijah Wald and a Q&A with Anderson, Wald, Preston Lauterbach, and Peter Guralnick, this book paints a vivid portrait of an elusive figure who forever changed the musical landscape as we know it.

-

A Rolling Stone-Kirkus Best Music Book of 2020

Winner of the Audiofile Earphones Award Publishers Weekly, "Most Anticipated Books of Spring 2020"

No Depression, "Best Music Books of 2020"

Best Classic Bands, "Best Music Books of the Year"

OnMilwaukee, "10 Great Books from 2020" -

"Anderson offers vivid, personal glimpses of her stepbrother ... providing a colorful picture .... [An] earnest and enlightening memoir."Publishers Weekly

-

"An illuminating portrait of an artist lost in the mists of history and mystery."Kirkus

-

"Annye Anderson's lush, vivid memories from Robert Johnson's home base give the bluesman a personal dimension like never before. How he walked, the pomade in his hair, his protection of his guitar. The aura of mystery remains, but with Brother Robert, Johnson gains character and context, and becomes more of a person than we've ever known this specter to be."RobertGordon, author of Can't Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Watersand It Came From Memphis

-

"Cutting through the mythos that has long surrounded this iconic artist, this is an intriguing addition to the history of 20th-century blues."Library Journal

-

"Although it's been more than 80 years since Anderson last saw Johnson, her memories are vivid and personal, as she recalls a well-loved older sibling who entertained his family and community with his guitar and vast repertoire of songs. [...] Anderson's account debunks myths about Johnson: he had a loving family; he was exposed to all kinds of popular music; he was not illiterate; and he did not go to the crossroads and sell his soul to the devil. Consider Anderson's heartfelt chronicle an earnest attempt to set the record straight."Booklist

-

"Anderson's a charming storyteller, and her stories provide a fresh perspective."No Depression

-

"A breathtaking look into the provenance of one of the 20th century's great musical minds, the social warp and woof of Black Memphis in the 1920s and '30s, and, in spite of racial violence that continues to this day, the persistence of family and the power of music."Memphis Flyer

-

"[This book reveals] "new details about everything from Johnson's birth to his romantic history to his life at home with family - even his favourite foods and brands of tobacco and pomade. The book also arrives with a new photograph of Johnson - just the third confirmed image in the world."CBC

-

"Mrs. Anderson summons up poignant memories of the young man she so admired... If Johnson has become an idealised figure, Anderson's book helps us to see him as a flesh-and-blood individual, an entertainer rather than some tortured mystic."The Times (UK)

-

"A remarkable book, one which so richly complements those that came before it documenting Robert Johnson's life and legacy."Under the Radar Magazine

-

"Rich... there is an intimacy that fires the story to life.”New York Review of Books

-

“[Brother Robert} book does much to pull the blues master out of the fog of myth.” (A Rolling Stone-Kirkus Best Music Book of 2020)Rolling Stone

-

"Intimate and warm."No Depression

-

"[This book] paints a lively portrait of the African American community in Memphis in the 1930s.”Daily Hampshire Gazette

-

"Brother Robert is, by my count, the twelfth book about Johnson, and it’s one of the best, because after decades of stories of the musician as a dark blues lord, Brother Robert, which featured a new photo of him smiling on the cover, humanizes Johnson, showing the musician from the perspective of a young girl."Texas Monthly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use