By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

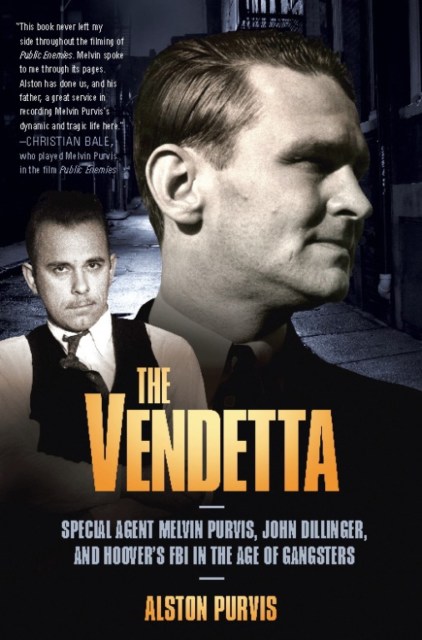

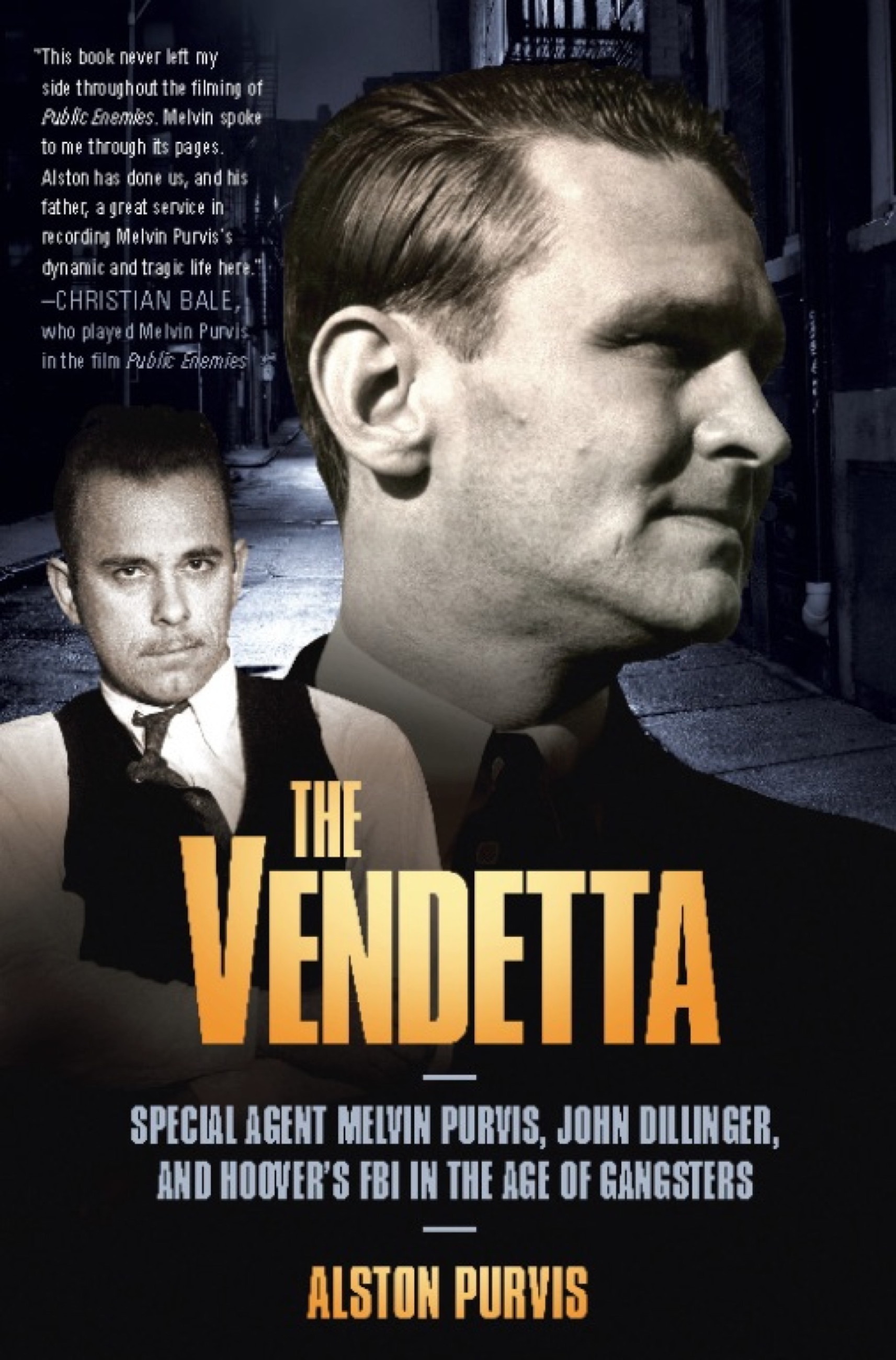

The Vendetta

Special Agent Melvin Purvis, John Dillinger, and Hoover's FBI in the Age of Gangsters

Contributors

With Alex Tresniowski

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 5, 2009

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786746668

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 5, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Alston Purvis is Melvin’s only surviving son. With the benefit of a unique family archive of documents, new testimony from colleagues and friends of Melvin Purvis and witnesses to the events of 1934, he has produced a grippingly authentic new telling of the gangster era, seen from the perspective of the pursuers. By finally setting the record straight about his father, he sheds new light on what some might call Hoover’s original sin — a personal vendetta that is one of the earliest and clearest examples of Hoover’s bitter, destructive paranoia.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use