Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

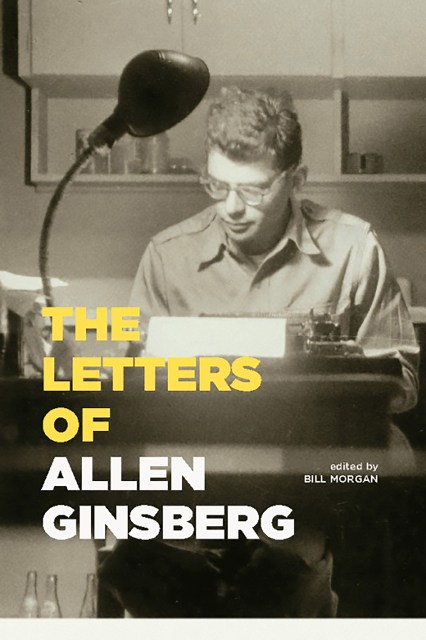

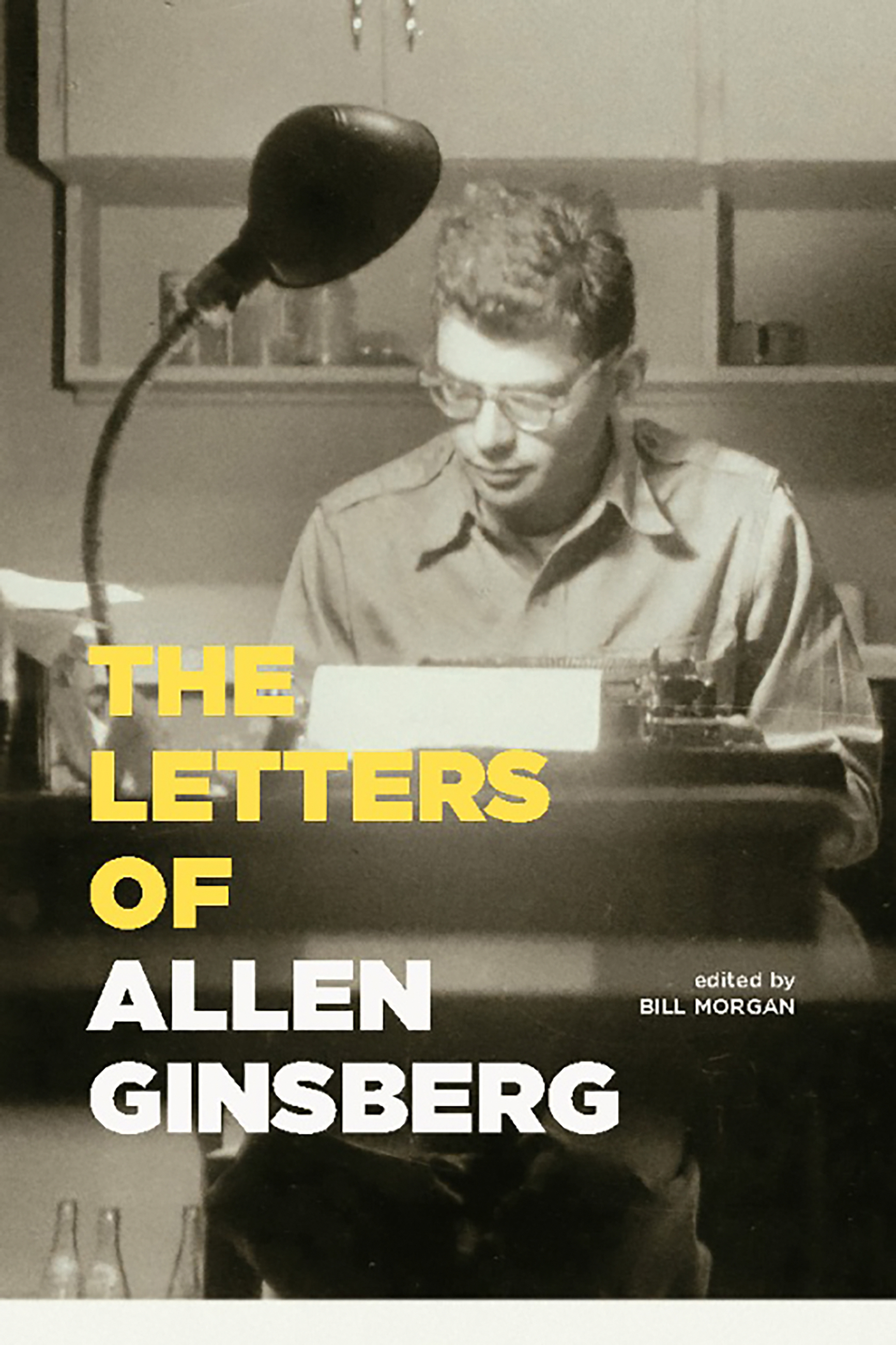

The Letters of Allen Ginsberg

Contributors

By Bill Morgan

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $18.99 $24.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 2, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Through his letter writing, Ginsberg coordinated the efforts of his literary circle and kept everyone informed about what everyone else was doing. He also preached the gospel of the Beat movement by addressing political and social issues in countless letters to publishers, editors, and the news media, devising an entirely new way to educate readers and disseminate information. Drawing from numerous sources, this collection is both a riveting life in letters and an intimate guide to understanding an entire creative generation.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 2, 2008

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786726011

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use