By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

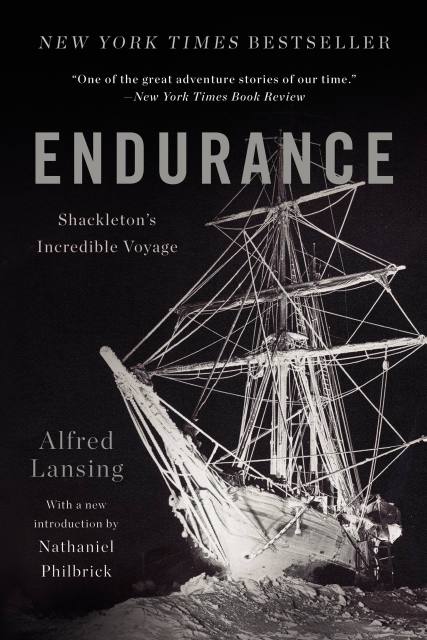

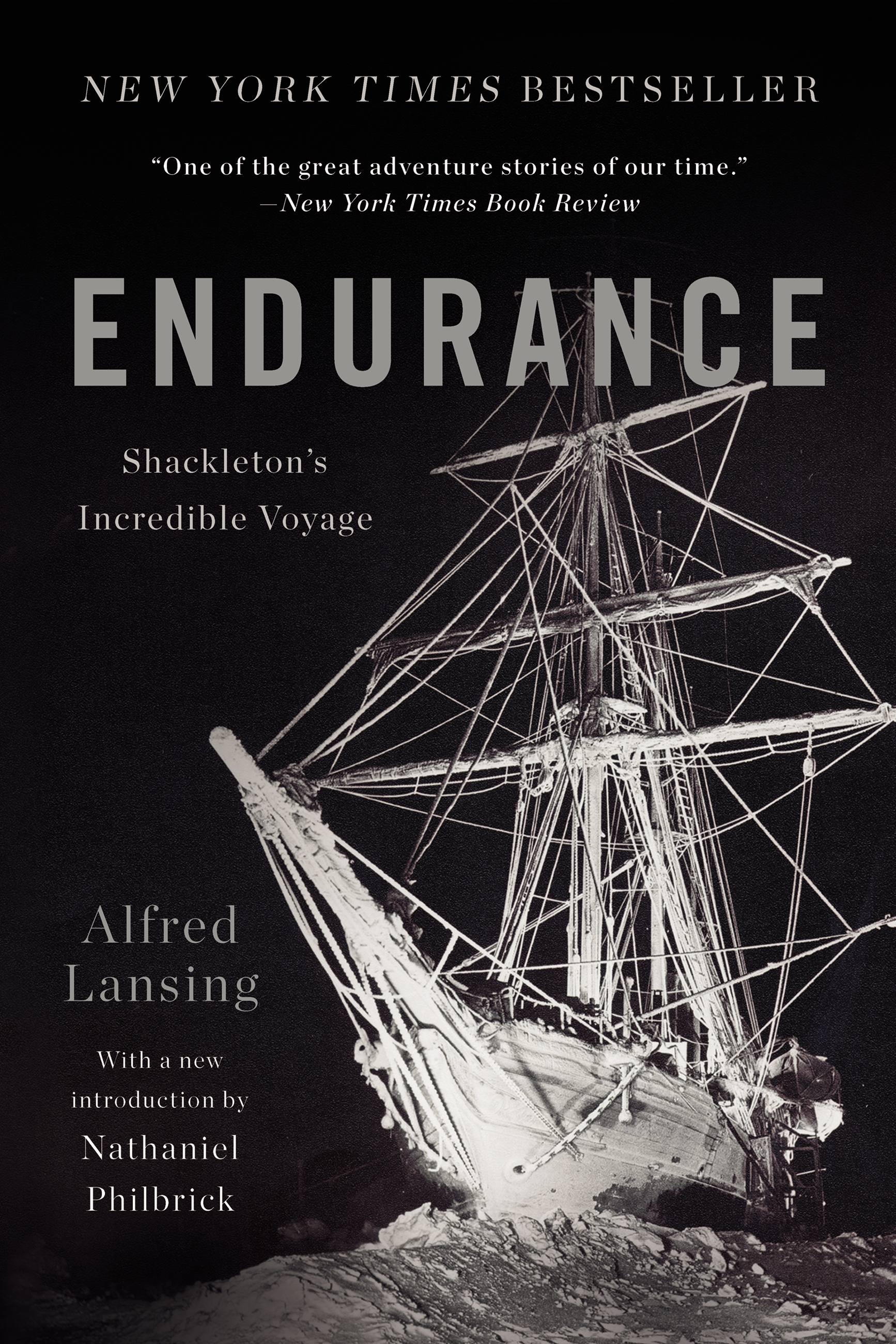

Endurance

Shackleton's Incredible Voyage

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 29, 2014

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465058792

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 29, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“One of the greatest adventure stories of our time.” –New York Times Book Review

In August 1914, polar explorer Ernest Shackleton boarded the Endurance and set sail for Antarctica, where he planned to cross the last uncharted continent on foot. In January 1915, after battling its way through a thousand miles of pack ice and only a day's sail short of its destination, the Endurance became locked in an island of ice. Thus began the legendary ordeal of Shackleton and his crew of twenty-seven men. When their ship was finally crushed between two ice floes, they attempted a near-impossible journey over 850 miles of the South Atlantic's heaviest seas to the closest outpost of civilization.

In Endurance, the definitive account of Ernest Shackleton's fateful trip, Alfred Lansing brilliantly narrates the harrowing and miraculous voyage that has defined heroism for the modern age.

Genre:

-

"One of the most gripping, suspenseful, intense stories anyone will ever read."Chicago Tribune

-

"Riveting."The New York Times

-

"Without a doubt this painstakingly written authentic adventure story will rank as one of the classic tales of the heroic age of exploration."Christian Science Monitor

-

"Grit in the face of seemingly insurmountable adversity."Wall Street Journal

-

"[An] incomparable telling of Shackleton's travails."Mary Roach, New York Times Book Review