By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

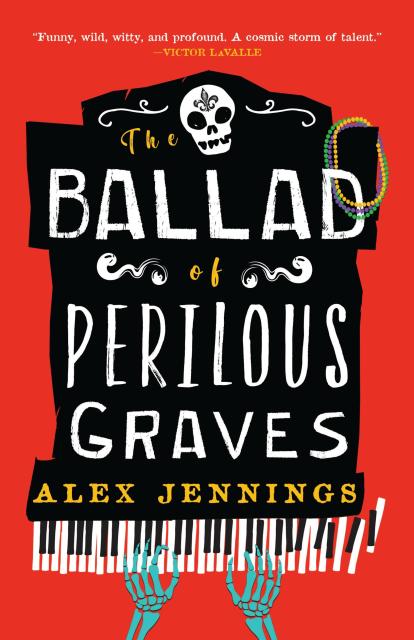

The Ballad of Perilous Graves

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 21, 2022

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Redhook

- ISBN-13

- 9780759557215

Price

$6.99Price

$8.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $6.99 $8.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 21, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

"Funny, wild, witty, and profound.”―Victor LaValle

"A wild and wonderful debut, teeming with music, family and art."—New York Times

"Magical, lyrical, gritty, otherworldly…hype like Bayou Classic in the 90s."—P. Djèlí Clark

One of the Best Fantasy Books of 2022: New York Times; Oprah Daily; Vulture; Gizmodo; Boston Public Library

A fun and fantastical love letter to New Orleans unfolds when a battle for the city's soul brews between two young mages, a vengeful wraith, and one powerful song in this wildly imaginative debut.

Perry knows Nola’s rhythm as intimately as his own heartbeat. So when the city’s Great Magician starts appearing in odd places and essential songs are forgotten, Perry knows trouble is afoot.

Nine songs of power have escaped from the piano that maintains the city’s beat, and without them, Nola will fail. Unwilling to watch his home be destroyed, Perry will sacrifice everything to save it. But a storm is brewing, and the Haint of All Haints is awake. Nola’s time might be coming to an end.

-

"A hallucinatory wonder of a debut with hints of dark humor and the intellectual challenge of Samuel Delaney. Brimming with language and music, this phantasmagoric novel taps the deep root of multi-cultural, multi-racial life in, and beyond, New Orleans. It’s an electrifying trip with zombie cabbies, sentient blues songs, parading graffiti tags, and the child mages Perilous “Perry” Graves, his sister Brendy and their best friend Peaches who must outwit, outstomp, and outplay to save NOLA’s, their city’s, our city’s, soul."Walter Mosley, New York Times bestselling author

-

“Alex Jennings did not come here to play. He came to swing, stride, and make prose sing. This novel is funny, wild, witty, and profound. The Ballad of Perilous Graves is the debut of a cosmic storm of talent.”Victor LaValle, author of The Changeling

-

“The Ballad of Perilous Graves takes readers on a glorious, gorgeously sinister, and phantasmagorical journey through New Orleans, in the company of an unforgettable hero and a cast of magical characters so real I ached to live in their world. A stunning debut that is sure to become a classic."Elizabeth Hand, author of Generation Loss and Hokuloa Road

-

"A wild and wonderful debut, teeming with music, family and art...This book is gorgeously written, with prose I wanted to eat off the page...The effervescent invention of Jennings’s work is dazzling."New York Times

-

"Stunning... Jennings develops a rich, enveloping world brimming with mesmerizing art, music, and fantasy, and sets within it a rich discussion of community and culture. The unmistakable love for New Orleans that emanates from these pages will stick in readers’ heads—and hearts—like the catchiest of tunes."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"A spectacularly original re-imagining of the myths and legends of New Orleans brought vividly to life through Jennings' wondrous prose. The Ballad of Perilous Graves is not only an engrossing adventure but a potent homage to the beating heart of one of the world's most magical cities."Ladee Hubbard, author of The Talented Ribkins

-

"Alex Jennings has composed a beautiful song full of magic and rhythm, darkness and delight. A profoundly gorgeous debut."Christina Henry, author of Near the Bone and Horseman

-

"The Ballad of Perilous Graves has got to be one of the most amazing books I’ve read in a minute. Magical, lyrical, gritty, otherworldly…sh*t is hype like Bayou Classic in the 90s."P. Djèlí Clark, author of The Master of Djinn

-

"Jennings weaves a brilliant tapestry... With wonderful imagery—living graffiti and personified songs and zombie nutria—and an emphasis on the importance of family, history, and music, The Ballad of Perilous Graves is a remarkable debut."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Full to bursting with surreal ideas, gloriously unique characters, unapologetic Blackness, and a soul-deep love for New Orleans and its people."Vulture, "The Best Fantasy Novels of 2022"

-

"An enchanting, energetic, wild ride of a story set to a staccato melody. The electric prose leaps off the page in a riot of colors and sounds. An astounding debut that will leave readers hungry for more.”Leslye Penelope, author of The Monsters We Defy

-

"Brimming with heart and imagination, The Ballad of Perilous Graves is a wild, dark and joyful love song to New Orleans, the power of stories, and hope in the face of destruction. A spectacular debut."H. G. Parry, author of The Magician's Daughter

-

"Like any good trip through New Orleans, The Ballad of Perilous Graves is both magical and musical, the result is a book you both see and hear. In other words, both an unforgettable story and an experience."Rion Amilcar Scott, author of The World Doesn't Require You: Stories

-

"Vital and appealing, vibrant and propulsive. Alex Jennings weaves together three of my favorite things — music, New Orleans, and magic. The Ballad of Perilous Graves is exactly what I wanted to read."Kelly Link

-

"Jennings’s post-Katrina haunted NOLA breathes fresh energy into modern Fantasy. His lyrical prose dances to a rhythm all its own."Stina Leicht, author of Persephone Station

-

"Jennings takes the reader on an intimate tour of New Orleans and her mirror-twin, the equally seductive and even stranger city of Nola. Jennings has an unsurpassed ear for New Orleans dialogue, and his tale is scary, sweet, lyrical, and real."Poppy Z. Brite

-

"I enjoyed The Ballad of Perilous Graves tremendously. Jennings writes with an energy and a profusion of imagination and vividness that carries you off to a secret New Orleans where music is magic. Brilliant!”Katherine Addison, author of The Goblin Emperor

-

"This ballad is a true picaresque, an adventure story…It’s an epic quest, a fantasy on a grand scale. It’s a big book in every way—length, vision, and most of all, heart."Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate

-

"Jennings has crafted a world that is warm, strange, loud and colorful, and brimming with magic and heart — this is New Orleans as you’ve never seen before."Apartment Therapy

-

"Jennings’ novel is a love letter to the real-life New Orleans, the power of music, and the bonds of community that hold us all together."Paste

-

"The two worlds of this gripping and inventive fantasy are so vividly depicted that reading it is a bit like taking a fabulous city break."The Guardian

-

"A literary and music-filled adventure...The Ballad of Perilous Graves is a must read."Locus

-

"The debut novel from an exceptionally creative author, Alex Jennings... [An] audacious, abundantly imaginative novel."Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

-

“In Alex Jennings’ spectacular debut, the city of New Orleans is transformed into a magical city where musical creatures and spirits, mages, and more flourish within the city’s limits.”Lightspeed Magazine

-

"New Orleans comes to magical, undead, vibrant life in the pages of this book, which is charged with a cadence that is entirely unique. The line writing of this book is so fantastic, switching in between the perspectives of a young teacher and three child-mages...An incredible, evocative, syrupy book that will not fail to enchant you."io9

-

"New Orleans is viewed through a fantastic lens in a lyrical novel stuffed with zombies, jazz and a magical Black culture. For readers looking for the next N.K. Jemisin."Center for Fiction

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use