Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

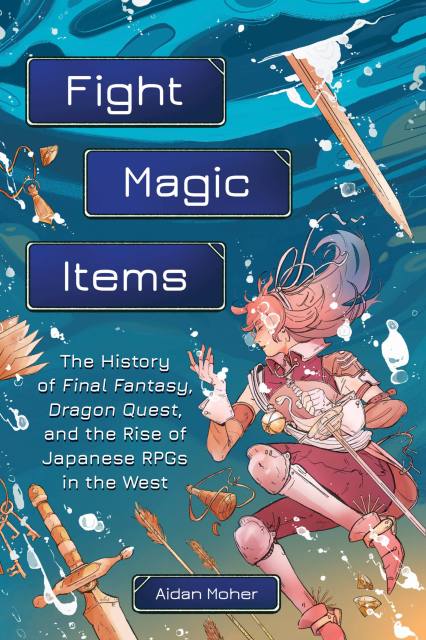

Fight, Magic, Items

The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West

Contributors

By Aidan Moher

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 4, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762479634

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 4, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Japanese roleplaying game (JRPG) genre is one that is known for bold, unforgettable characters; rich stories, and some of the most iconic and beloved games in the industry. Inspired by early western RPGs and introducing technology and artistic styles that pushed the boundaries of what video games could be, this genre is responsible for creating some of the most complex, bold, and beloved games in history—and it has the fanbase to prove it. In Fight, Magic, Items, Aidan Moher guides readers through the fascinating history of JRPGs, exploring the technical challenges, distinct narrative and artistic visions, and creative rivalries that fueled the creation of countless iconic games and their quest to become the best, not only in Japan, but in North America, too.

Moher starts with the origin stories of two classic Nintendo titles, Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, and immerses readers in the world of JRPGs, following the interconnected history from through the lens of their creators and their stories full of hope, risk, and pixels, from the tiny teams and almost impossible schedules that built the foundations of the Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest franchises; Reiko Kodama pushing the narrative and genre boundaries with Phantasy Star; the unexpected team up between Horii and Sakaguchi to create Chrono Trigger; or the unique mashup of classic Disney with Final Fantasy coolness in Kingdom Hearts. Filled with firsthand interviews and behind-the-scenes looks into the development, reception, and influence of JRPGs, Fight, Magic, Items captures the evolution of the genre and why it continues to grab us, decades after those first iconic pixelated games released.

-

"A wondrous in-depth look at the history of Japanese role playing games.”Engadget

-

"Aidan Moher has literally written the book on Japanese role-playing games.”ComicBook.com

-

“A work that will resonate with many of us who grew up with the genre and watched its rise as we ourselves grew into adulthood.”RPGFan

-

"A fun, fascinating exploration of the medium’s most magical genre.”Nicholas Eames, author of Kings of the Wyld

-

"Informative, personal, and fascinating, this book earns its place among deep dives into video-game history.”Mary Kenney, author of Gamer Girls

-

"Fight, Magic, Items is the intricate deep dive that the JRPG genre deserves.”Daniel Dockery, author of Monster Kids

-

"Strong research that’s fun to read, alongside moving anecdotes and nostalgia? Take my money.”Andy Campbell, author of We Are Proud Boys and Senior Editor at Huffington Post