By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

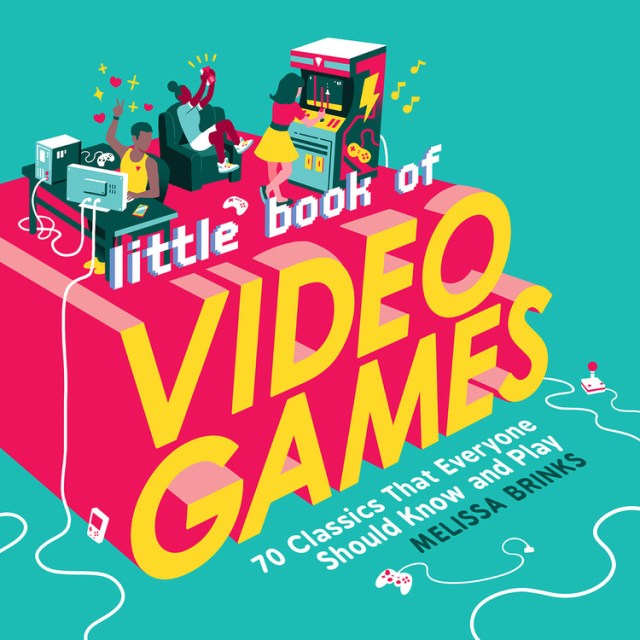

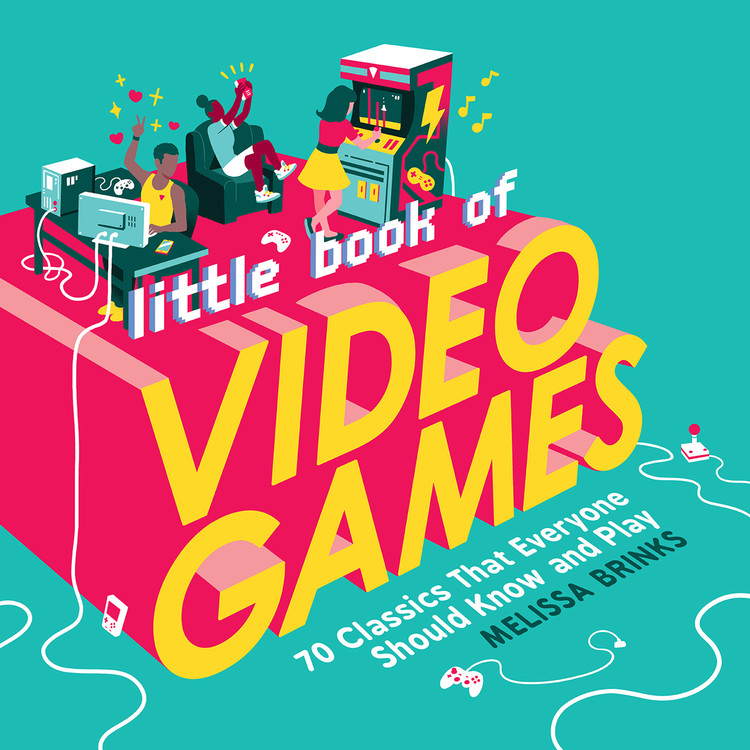

Little Book of Video Games

70 Classics That Everyone Should Know and Play

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 160 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762496570

Price

$15.00Price

$20.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $15.00 $20.00 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Revisit your favorites, find something new, or play your way through this light-hearted guide to the most celebrated and iconic arcade, console, and computer games from the 1950s to the 2000s.

An accessible, informative look at the history and evolution some of the most popular and iconic video games from their early beginnings up to the 2000s. Author Melissa Brinks explores each influential game and its impact on they would have on the games that would follow, with brief, engaging profiles and surprising trivia that is perfect for fans of all levels.

From the groundbreaking games of the 1950s to the genre-defining games of the 60s and 70s to the modern classics of the 1990s and early 2000s, The Little Book of Video Games includes games from a wide variety of genres and consoles including (but not limited to): Pong, Spacewar!, Adventure, Pac-Man, Rogue, Donkey Kong, Galaga, Dragon’s Lair, Tetris, Super Mario Bros., The Oregon Trail, Castlevania, Legend of Zelda, Final Fantasy, Mega Man, SimCity, Mother, Mortal Kombat, Myst, Doom, Warcraft, Diablo, Tomb Raider, Pokémon, Tamagotchi, GoldenEye 007, Ultima Online, Metal Gear Solid, Dance Dance Revolution, Half-Life, Silent Hill, The Sims, and more.

Now you can learn, share, and enjoy your favorite classic video games without having to press a power button!

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use