Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

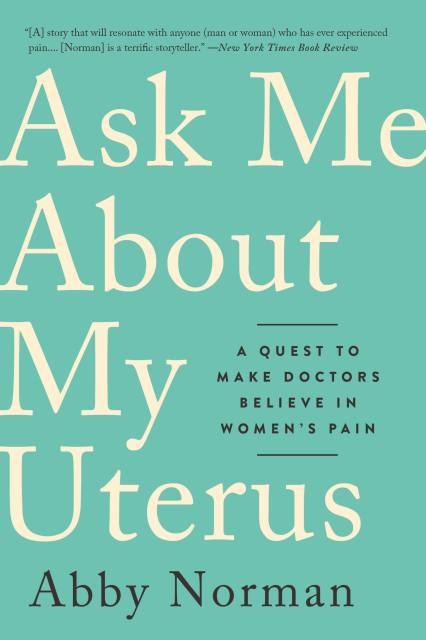

Ask Me About My Uterus

A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women's Pain

Contributors

By Abby Norman

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In the fall of 2010, Abby Norman’s strong dancer’s body dropped forty pounds and gray hairs began to sprout from her temples. She was repeatedly hospitalized in excruciating pain, but the doctors insisted it was a urinary tract infection and sent her home with antibiotics. Unable to get out of bed, much less attend class, Norman dropped out of college and embarked on what would become a years-long journey to discover what was wrong with her. It wasn’t until she took matters into her own hands — securing a job in a hospital and educating herself over lunchtime reading in the medical library — that she found an accurate diagnosis of endometriosis.

In Ask Me About My Uterus, Norman describes what it was like to have her pain dismissed, to be told it was all in her head, only to be taken seriously when she was accompanied by a boyfriend who confirmed that her sexual performance was, indeed, compromised. Putting her own trials into a broader historical, sociocultural, and political context, Norman shows that women’s bodies have long been the battleground of a never-ending war for power, control, medical knowledge, and truth. It’s time to refute the belief that being a woman is a preexisting condition.

Genre:

-

Selected as one of the top ten titles in Lifestyle for Spring 2018.Publishers Weekly

-

"Required reading for anyone who is a woman, or has ever met a woman. This means you."Jenny Lawson, authorof Let's Pretend This Never Happened and FuriouslyHappy

-

"This book deals with such an important subject. Abby Norman's odyssey with her own health is sadly an all too common story to those of us who suffered in silence for so long. My hope is that anyone involved in women's health will read her story and revisit the way we treat women and their health concerns in our culture."Padma Lakshmi, NewYork Times best-selling author and co-founder of the EndometriosisFoundation of America

-

"A fresh, honest, and startling look at what it means to exist in a woman's body, in all of its beauty and pain. Abby's voice is inviting, unifying, and remarkably brave."Gillian Anderson, Actress, activist and co-author of We: A Manifesto For Women Everywhere

-

"[Norman] builds a convincing case that women describing discomfort are more likely than men to be dismissed by physicians, but along the way tells a story that will resonate with anyone (man or woman) who has ever experienced pain.... [She] is a terrific storyteller with a gift for weaving memorable anecdotes, some drawn from medical history, others from recent scientific debates and most plucked from her own travails... Norman's life is much more than a disease.... [An] important addition to a long tradition of pain memoirs. Norman shares a particular tale of suffering but expresses a common frustration about the dearth of words to convey pain. Any schoolgirl can talk about love, Virginia Woolf famously said, but 'let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.'"New York Times Book Review

-

"Compelling and impressively, Norman's narrative not only offers an unsparing look at the historically and culturally fraught relationship between women and their doctors, it also reveals how, in the quest for answers and good health, women must still fight a patriarchal medical establishment to be heard. Disturbing but important reading."Kirkus Reviews

-

"From wandering wombs to ovary compressors, Abby Norman's book is packed with fascinating historical detail about how women's bodies have been misunderstood and mistreated by male doctors for centuries. It is also an important reminder that there is still a culture of silence surrounding women's gynecological health in the twenty-first century, and that there is work yet to be done when it comes to advocating for women's healthcare."LindseyFitzharris, author of The Butchering Art

-

"With searing prose, science writer and editor Norman pens a heartfelt medical history and memoir of coming to terms with the limitations of one's physical body....A thoughtful read."Library Journal

-

"Abby Norman writes powerfully about her experience living with endometriosis and presents research on the disease and the history of women who were brushed off by medical professionals. You know, like how hysteria is anything that ails a woman, but the same symptoms do not equate hysteria in a man. It's hitting all my feminist and history and medicine buttons."Book Riot

-

"Author and activist Abby Norman, has put decades of labor-including careful, independent medical study-into studying this phenomenon, as she describes in her book Ask Me About My Uterus, both a memoir and a trenchant manifesto."The New Republic

-

"Read this book, share this book with a man in your life and consider this our full permission to storm off dramatically if someone suggests you 'just take a couple Advil and quit complaining'."Purewow

-

"Norman doesn't sugarcoat just how difficult it can be to convince doctors that pain is legitimate. Instead, she offers searing commentary on how women have been conditioned to avoid seeking treatment or admitting that we feel bad in the first place."The Cut

-

"Norman, now a science writer, articulates her own struggles with clarity and calmness."Washington Post

-

"Tell[s] an alarming story about how difficult it is for women to access quality care; particularly those women suffering from poorly understood autoimmune disorders.... Leave[s] the reader galvanized, not despairing."The New York Times

-

"Eye-opening."Bustle

-

"Journalist and advocate Abby Norman uproots the paradigm that women must suffer their pain alone and in silence....a respectable entry into this genre of women's pain....As Norman puts it, the patriarchy of pain doesn't have to be the norm."Pacific Standard

-

"Compelling....showing the toll poorly treated illness takes on a woman's life and the heroic effort required to contribute to the world regardless."Ms. Magazine

-

"Ask Me About My Uterus educates from the perspective of the ill-a side rarely seen as in depth as it is in this incredible read."BUST

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585826

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use